Elon Musk and coronapanic

From Elon Musk by Walter Isaacson…

“The coronavirus panic is dumb,” Musk tweeted. It was March 6, 2020, and COVID had just shut down his new factory in Shanghai and begun to spread in the U.S. That was decimating Tesla’s stock price, but it was not just the financial hit that upset Musk. The government-imposed mandates, in China and then California, inflamed his anti-authority streak.

It was not being pro-Science that prevented Musk from embracing measures that proved ineffective against SARS-CoV-2, but a mindless anti-authority attitude. (Keep in mind that the author is a huge hater of Donald Trump, a passionate supporter of Democrats, and a believer in cloth masks against an aerosol virus)

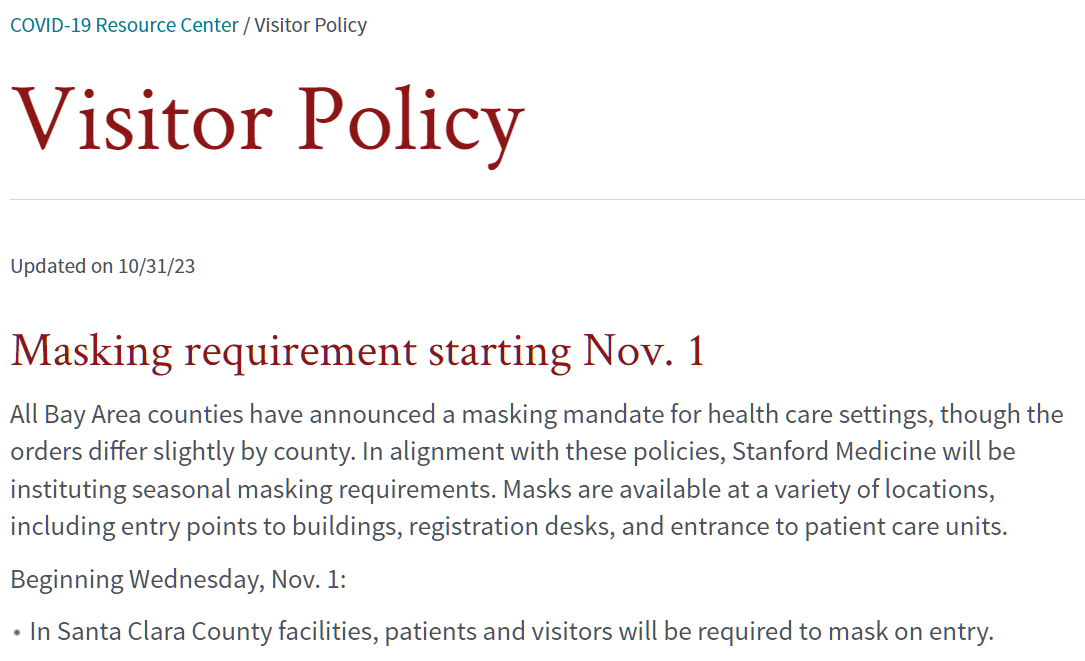

When California issued a stay-at-home order later in March, just when the Fremont factory was starting to produce the Model Y, he became defiant. The factory would remain open. He wrote in a company-wide email, “I’d like to be super clear that if you feel the slightest bit ill or even uncomfortable, please do not feel obligated to come to work,” but then he added, “I will personally be at work. My frank opinion remains that the harm from the coronavirus panic far exceeds that of the virus itself.” After county officials threatened to force the plant to shut down, Musk filed suit against the orders. “If somebody wants to stay in their house, that’s great,” Musk said. “But to say that they cannot leave their house, and they will be arrested if they do, this is fascist. This is not democratic. This is not freedom. Give people back their goddamn freedom.” He kept the plant open and challenged the county sheriff to make arrests. “I will be on the line with everyone else,” he tweeted. “If anyone is arrested, I ask that it only be me.” Musk prevailed. The local authorities reached an agreement with Tesla to let the Fremont factory stay open so long as certain mask-wearing and other safety protocols were followed. These were honored mainly in the breach, but the dispute died down, the assembly line churned out cars, and the factory experienced no serious COVID outbreak.

The controversy became a factor in his political evolution. He went from being a fanboy and fundraiser for Barack Obama to railing against progressive Democrats.

(It cannot be that Democrats evolved, e.g., from being against same-sex marriage to being in favor of gender affirming surgery for teenagers. It is Musk who changed.)

Musk does not love our nation’s second most famous warrior against COVID-19:

… he wasn’t impressed by Joe Biden. “When he was vice president, I went to a lunch with him in San Francisco where he droned on for an hour and was boring as hell, like one of those dolls where you pull the string and it just says the same mindless phrases over and over.”

“Biden is a damp sock puppet in human form,” Musk responded [regarding Biden’s celebration of GM as the most important company in EVs at a time when GM was shipping 26 cars per calendar quarter]

Nor did Musk appreciate the evolution of California progressivism:

“I came there when it was the land of opportunity,” he says. “Now it’s the land of litigation, regulation, and taxation.”

Isaacson, much as he hates Republicans, attributes Musk’s mind-poisoning to libertarianism. But for this poison, Isaacson suggests, Musk might still be among the righteous. How stupid are libertarians? Isaacson describes Peter Thiel not wearing a seatbelt while Musk drives and crashes a McLaren:

Thiel got a ride with Musk in his McLaren. “So, what can this car do?” Thiel asked. “Watch this,” Musk replied, pulling into the fast lane and flooring the accelerator. The rear axle broke and the car spun around, hit an embankment, and flew in the air like a flying saucer. Parts of the body shredded. Thiel, a practicing libertarian, was not wearing a seatbelt, but he emerged unscathed.

Isaacson doesn’t explain why John Stuart Mill and Milton Friedman are against seatbelts in supercars. (I would like an explanation of why the rear axle broke! A pothole on Sand Hill Road?!? Quelle horreur! Acceleration per se doesn’t seem like a plausible cause. In the video below, Musk says “the rear end broke free”; Isaacson, the Harvard graduate, may not have understood that this describes wheelspin, not the rear axle and wheels coming off the car.)

Speaking of coronapanic, Musk and Bill Gates meet in March 2022. They had to agree to disagree on Mars colonization (Gates thinks lacks practical value, as do I, though planning to get to Mars means that if you fail your engineering work makes getting to orbit dirt cheap.)

At the end of the tour, the conversation turned to philanthropy. Musk expressed his view that most of it was “bullshit.” There was only a twenty-cent impact for every dollar put in, he estimated. He could do more good for climate change by investing in Tesla. “Hey, I’m going to show you five projects of a hundred million each,” Gates responded. He listed money for refugees, American schools, an AIDS cure, eradicating some mosquito types through gene drives, and genetically modified seeds that will resist the effects of climate change. Gates is very diligent about philanthropy, and he promised to write for Musk a “super-long description of the ideas.”

Money for refugees? I haven’t heard of Bill Gates doing anything for the 1.7 million Afghans recently expelled from Pakistan nor for the nearly 400,000 Palestinians expelled by Kuwait. Gates wants to fight climate change and also make some money betting that nobody wants electric cars:

Gates had shorted Tesla stock, placing a big bet that it would go down in value. He turned out to be wrong. By the time he arrived in Austin, he had lost $1.5 billion. Musk had heard about it and was seething. Short-sellers occupied his innermost circle of hell. Gates said he was sorry, but that did not placate Musk. “I apologized to him,” Gates says. “Once he heard I’d shorted the stock, he was super mean to me, but he’s super mean to so many people, so you can’t take it too personally.” The dispute reflected different mindsets. When I asked Gates why he had shorted Tesla, he explained that he had calculated that the supply of electric cars would get ahead of demand, causing prices to fall.

[after Gates keeps hitting Musk up for cash] “Sorry,” Musk shot back instantly. “I cannot take your philanthropy on climate seriously when you have a massive short position against Tesla, the company doing the most to solve climate change.”

“At this point, I am convinced that he is categorically insane (and an asshole to the core),” Musk texted me right after his exchange with Gates. “I did actually want to like him (sigh).”

Musk’s investments in Neuralink should be considered nonprofit donations in my opinion. This is blue sky research of the type that governments typically fund because there is no reasonable expectation of a return on investment.

Full post, including comments