Veterans Day book: Call Sign Kluso

For pilots who want to observe Veterans Day by learning about how the F-15 is flown in combat, let me recommend Call-Sign KLUSO: An American Fighter Pilot in Mr. Reagan’s Air Force by Rick Tollini.

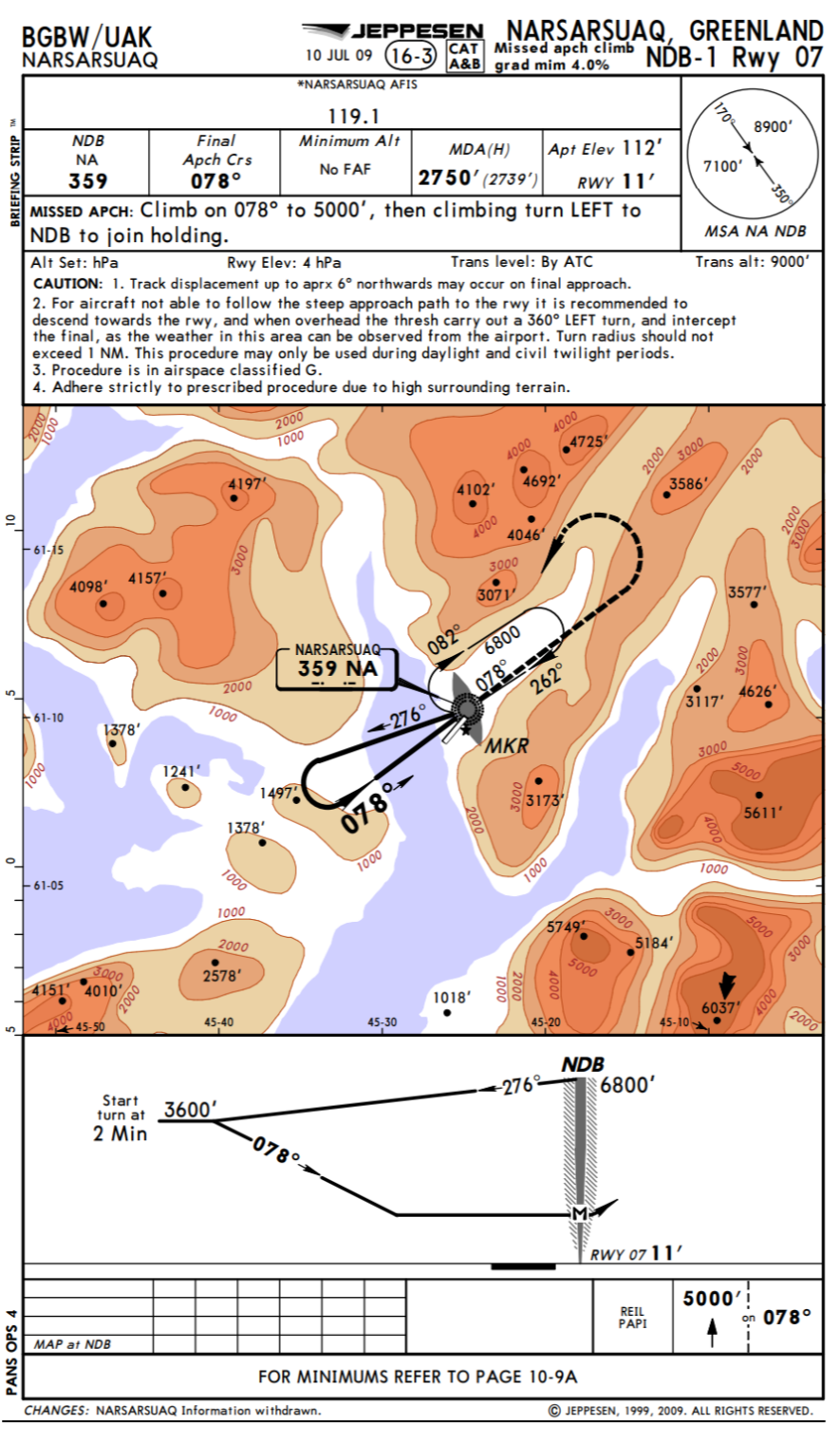

How about those tight formations that we see when the Blue Angels and Thunderbirds perform. That’s how you go into a fight, right? Wrong! Here is how 4 F-15s are arranged to head into Iraq from Saudi Arabia at night:

The basic formation was a little bit wider than a normal daytime formation just to assist with flight path deconfliction and to reduce the workload on the wingman spending time on formation management. About 5nm between #1 (flight lead) and #3 (element lead) with the wingman on the outside of the formation, about 2–3nm away from their respective flight leads. This doubled the total width of the formation from 5nm wide to about 10nm wide. A standardized altitude deconfliction plan was also utilized based on a briefed “base” altitude for the flight lead. So, if the flight lead’s “base” altitude was 25,000 feet, then #3 might be 2,000 feet below, and the wingmen would be 1,000–2,000 feet above their respective flight leads. Any time the “base” altitude changed, the flight members would flex to the new relative deconfliction altitudes. Having the wingman slightly above their flight leads also helped with visual mutual support for the wingmen. That’s right … “visual” at night without NVGs.

If the F-15 is so great, why bother with four at a time? Why not send one to defeat the enemy?

A cold hard fact that has been forgotten and relearned, usually through misfortune, is that a single fighter jet is not an effective combat unit and is more of a liability than anything else. The enemy will grow a brave heart when they know they have a solitary American fighter pilot alone in his aircraft. Even if they should lose a pilot or jet of their own, they will attack confident of downing such a precious prize as an American fighter. If there is another supporting fighter within visual range, then the enemy will begin to lose his courage and doubt his own ability to be victorious. It’s called Mutual Support, and it is the bedrock of air combat tactics. I learned that lesson at my first COPE THUNDER, and I would never forget it.

How did our USAF heroes stay healthy without the marijuana that Maskachusetts and California say is “essential” and, from a medical point of view, super beneficial?

The other key player in this plan was Kory, our flight doc. Kory had been issued a truckload of amphetamines (specifically Dexedrine), or uppers, and the previously mentioned Restoril (downers), and he would be our acting “dealer.” All pilots at some point in our careers had been tested with both pills to insure we did not have any unusual side effects (other than the desired or expected ones), but most of us had never actually experienced using either regularly. The Restoril was to make sure that we could get to sleep quickly and soundly for the small window of opportunity we would have each day between combat missions. The Dexadrine was intended to keep us alert (and in some cases from actually falling asleep) in the cockpit.

Reminding us to “check 6” even after we vanquish the only cause of death that is now on anyone’s mind (i.e., coronaplague):

My roommate for the duration of the deployment was Capt Rory “Hoser” Draeger. Hoser was actually a young flight lead in the Dirty Dozen when I first arrived at Kadena. … I knew he was an outstanding aviator and, being from Kadena originally, he was somebody I could count on to lead some of our more difficult large-force missions. Also, we would need everybody we could get. Hoser and I were not “best friends” by any means, but we got along well together and gave each other “space” as roommates. Not too long after the war, I received news that Hoser was killed in a car accident. Apparently, he was a passenger riding with some friends when the driver lost control and went off the road. Very sad … and ironic to survive a war and be killed in a random accident.

Tollini writes about the modern rules-bound military compared to the 1980s, in which it was, according to him, more about personal responsibility:

The USMTM [a military training liaison base] in Tabuk had very nice apartments (for the residents only, not us), a great swimming pool, and its best asset … a fully stocked bar! There was supposed to be no alcohol allowed on base while we were in-country, but the USMTMs were different. They were a little piece of “America” and had immunity from local laws and customs. So when the Gorillas first arrived in Tabuk all the pilots would head to the USMTM on any given night they could, that is until General Order No. 1 (GO#1) was issued.

GO#1 would (in my opinion) become one of the worst decisions ever in the annals of military history. It was issued by General Norman Schwarzkopf (the commander of US Central Command/CENTOM) and the order stated there would be absolutely NO drinking in the Kingdom. This was hopefully to show “solidarity” with our Saudi hosts and not insult their cultural sensibilities. Even most Saudis I met who heard about this no-drinking order thought it was crazy. They really didn’t care if we drank as long as we behaved.

I now believe the long-term effect of this original GO#1 was that it tried to mandate good order and discipline via a “general order,” rather than to establish this with good leadership and respect up and down the chain of command. From then on, any chance a commanding officer had to create an appearance of “good order and discipline” quickly and easily, he would just start signing out these types of “General Orders” and absolve himself of any responsibility to actually “lead” beyond that point. It was such a crock, and the troops could see right through it. I saw it as kind of the opposite of how Opec Hess treated us that first day in Thailand. Our leadership no longer trusted us. If you think there might be a problem with behavior and leadership in today’s military, I believe the root cause goes all the way back to Stormin’ Norman’s original GO#1.

The F-15 could use a $659 ashtray ($1,727 when we adjust 1985 dollars to today’s Bidie-bucks):

It went so far that Cherry and I (and some others) would smoke in the jets while flying our DCA CAP missions. I had found that I could use these little plastic powdered-lemonade drink cups (which had a foil lid) that fit perfectly between the light control panel knobs on the right side of the F-15 cockpit. So, I had a little ashtray I could use in flight, and when I was done I would just wrap the foil cover back over the top of the cup to prevent spillage. It was perfect. We didn’t smoke when anything important was going on, but for a four- or six-plus hour mission boring holes in the sky, it was a nice “break” to look forward to every hour or so. If I ever took off without a pack of smokes and lighter in my G-suit pocket, I knew it was going to be a long and grueling flight.

After years spent in Japan, Thailand, and the Philippines:

Saudi Arabia was a strange country. I don’t mean that necessarily in a bad way, but just that it felt “strange” being there. I had been in a lot of foreign countries, but this was the first time I had felt like such a “foreigner,” like I did not belong there. The people were nice enough, and most of us even made friends with many of the Saudi pilots. But it just always felt like there was some kind of barrier, as if we were the houseguests that had impolitely overstayed our visit. Our hosts would never say anything to us, but I felt they probably really preferred it if we would leave, as soon as possible. And, frankly, I felt the same way.

From the Boeing web site (source of the above photo):

The F-15 is an affordable, low-risk solution that maintains capacity and adds capability to the U.S. Air Force while preserving the Air Superiority and Homeland Defense missions.

Given the rate of inflation in Cirrus SR22 prices, the F-15 might well be considered “affordable” soon enough!

Full post, including comments