Why are there so many Americans still working?

Happy Halloween! It has felt like Halloween for the past 20 months or so, with ordinary Americans dressing up as surgeons or asbestos remediators in masks.

I’ve recently had occasion to take some prison galley-style JetBlue flights, in which flight attendants walk up and down the aisle looking for people who aren’t wearing masks correctly. The ticket counter at PBI has a high clear plastic barrier that makes communication between agent and customer almost impossible (while simultaneously providing no protection against COVID, according to the New York Times). The workers behind the plastic, have been stuck wearing masks for 8 hours per day for all 20 months of “14 days to flatten the curve.” I asked a 13-year veteran of the ticket counter how many of her colleagues had quit. “Everyone who could retire has done so,” she responded. She was sick of wearing a mask, found it frustrating to try to make herself understood, and did not think the mask was effective at preventing COVID infection. Like most other customer service businesses, the airport is extremely short staffed and, despite a reduced passenger volume, lines can get long (except at TSA, which seems to have infinite capacity!).

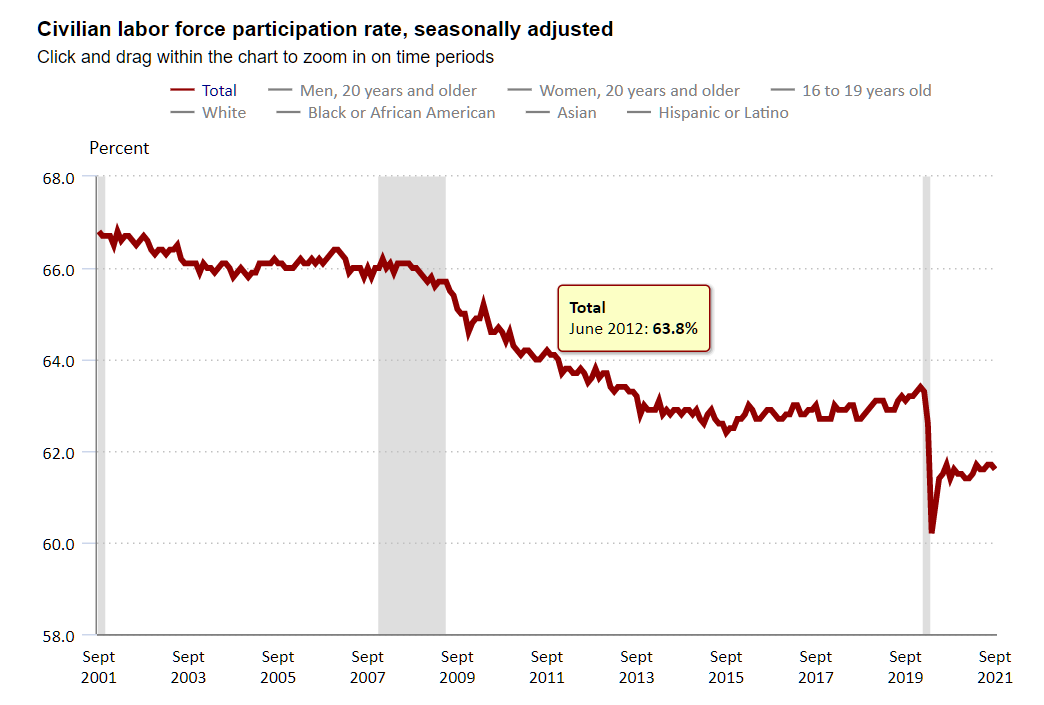

There has been a lot of media coverage regarding how few Americans are working. And, indeed, the stats do show that Americans are passionate about relaxing at home:

What I find confusing, however, is that so many Americans are working at these masks-all-day jobs (though I am grateful for their service!). It can’t be because the masks don’t bother them, since the people I’ve talked to say that they do find the masks uncomfortable. It can’t be because there aren’t any no-mask-required jobs available because, at least here in Florida, there are plenty. It shouldn’t be because it is too hard to transition to disability, because “Long COVID” is a recognized disability and the symptoms encompass almost any medical malady.

I’m not saying that labor force participation should be 0%. After all, there are plenty of high-paid masked jobs (surgeon) and plenty of medium-paid no-mask jobs (work from home, e.g.). But why isn’t labor force participation rate down closer to the Puerto Rican number (42 percent)? It can’t be fun to spend the whole day wearing a mask and asking in-a-rush airline passengers to repeat themselves.

Related:

- “4.3 million workers are missing. Where did they go?” (WSJ, 10/14; paywall-free version): More than a year and a half into the pandemic, the U.S. is still missing around 4.3 million workers. That’s how much bigger the labor force would be if the participation rate—the share of the population 16 or older either working or looking for work—returned to its February 2020 level of 63.3%. In September, it stood at 61.6%. … Of 52 economists surveyed by The Wall Street Journal, 22 predicted that participation would never return to its pre-pandemic level.