The Federal Reserve Bank president who said not to print money

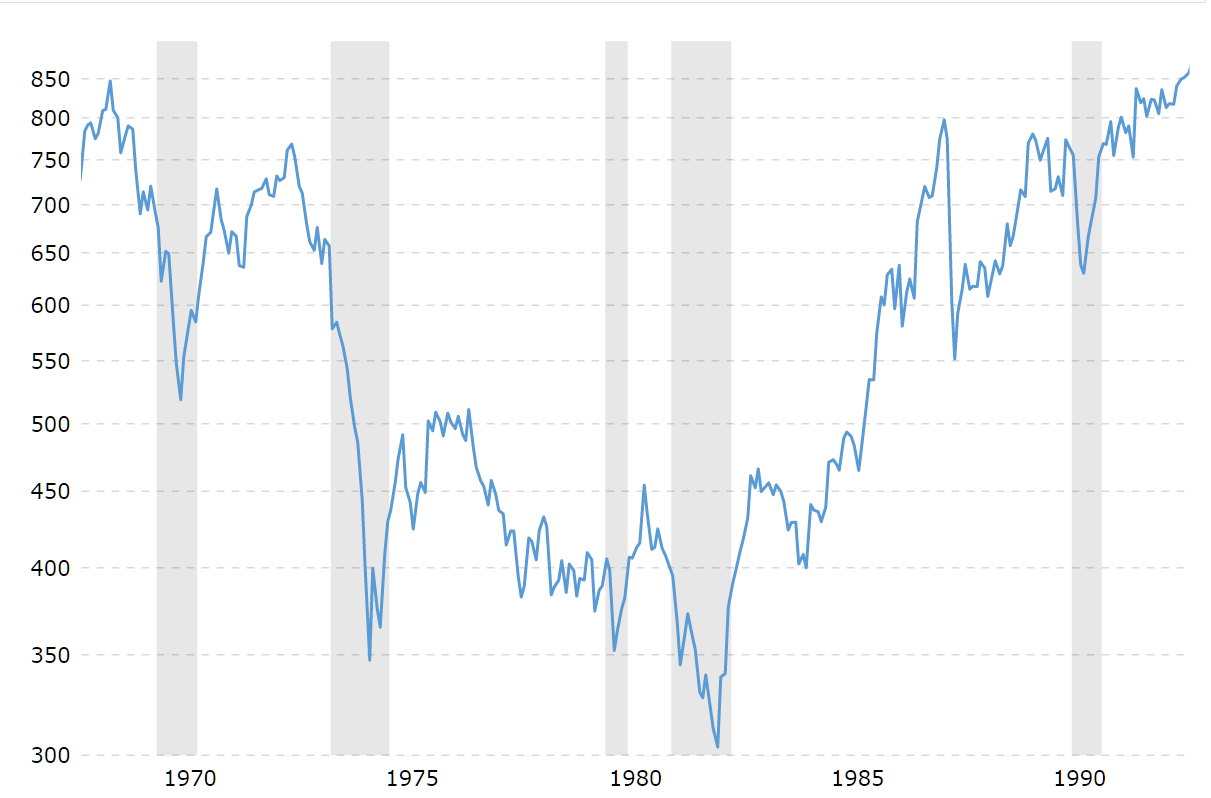

Happy Lucky 13 day! Given the recent headlines, e.g., “Inflation rises 7% over the past year, highest since 1982” (CNBC), let’s look at “The Fed’s Doomsday Prophet Has a Dire Warning About Where We’re Headed” (Politico).

In 2010, Hoenig was president of the Federal Reserve regional bank in Kansas City. As part of his job, Hoenig had a seat on the Fed’s most powerful policy committee, and that’s where he lodged one of the longest-running string of “no” votes in the bank’s history.

Between 2008 and 2014, the Federal Reserve printed more than $3.5 trillion in new bills. To put that in perspective, it’s roughly triple the amount of money that the Fed created in its first 95 years of existence. Three centuries’ worth of growth in the money supply was crammed into a few short years. The money poured through the veins of the financial system and stoked demand for assets like stocks, corporate debt and commercial real estate bonds, driving up prices across markets. Hoenig was the one Fed leader who voted consistently against this course of action, starting in 2010. In doing so, he pitted himself against the Fed’s powerful chair at the time, Ben Bernanke, who was widely regarded as a hero for the ambitious rescue plans he designed and oversaw.

Hoenig lost his fight. Throughout 2010, the FOMC votes were routinely 11 against one, with Hoenig being the one. He retired from the Fed in late 2011, and after that, a reputation hardened around Hoenig as the man who got it wrong. He is remembered as something like a cranky Old Testament prophet who warned incessantly, and incorrectly, about one thing: the threat of coming inflation.

So… he predicted inflation but was off by about 12 years as to when it would arrive? How is that different or better than predicting a big stock market crash at some point in the future?

But this version of history isn’t true. While Hoenig was concerned about inflation, that isn’t what solely what drove him to lodge his string of dissents. The historical record shows that Hoenig was worried primarily that the Fed was taking a risky path that would deepen income inequality, stoke dangerous asset bubbles and enrich the biggest banks over everyone else. He also warned that it would suck the Fed into a money-printing quagmire that the central bank would not be able to escape without destabilizing the entire financial system.

The Fed is now in a vise. Inflation is rising faster than the Fed believed it would even a few months ago, with higher prices for gas, goods and automobiles being fueled by the Fed’s unprecedented money printing programs. This comes after years of the Fed steadily pumping up the price of assets like stocks and bonds through its zero-percent interest rates and quantitative easing during and after Hoenig’s time on the FOMC. To respond to rising inflation, the Fed has signaled that it will start hiking interest rates next year. But if that happens, there is every reason to expect that it will cause stock and bond markets to fall, perhaps precipitously, or even cause a recession.

How does centrally-planned inflation work?

When the Fed kept interest rates low during the 1970s, it encouraged farmers around Kansas City to take on more cheap debt and buy more land. As cheap loans boosted demand for land, it pushed up land prices — something that might be expected to cool off demand.

But the logic of asset bubbles has the opposite effect. Rising land prices actually enticed more people to borrow money and buy yet more land because the borrowers expected the land value to only increase, producing a handsome payoff down the road. Higher prices led to more borrowing, which led to higher prices and more borrowing still. The wheel continued to spin as long as debt was cheap compared to the expected payoff of rising asset prices.

The bankers’ logic followed a similar path. The bankers saw farmland as collateral on the loans, and they believed the collateral would only rise in value. This gave bankers the confidence to keep extending loans because they believed the farmers would be able to repay them as land prices increased. This is how asset bubbles escalate in a loop that intensifies with each rotation, with the reality of today’s higher asset prices driving the value of tomorrow’s asset prices ever higher, increasing the momentum even further.

And the central planners, back in the 1980s messed up the flip side of this too, causing bank failures when farmland prices fell only 27 percent.

I recommend the article for its historical perspective. Don’t complain if you don’t find a solution to our current situation (high inflation; mediocre economic growth once adjusted for population growth). Part of this banker’s point was that there is no good way to stop printing money.

What did cars look like the last time inflation was this high? Here’s an example from a classic car gathering in our neighborhood:

Full post, including comments