Washington State’s new income tax and Florida’s new billionaire resident

We are informed that Floridians are crushed under the boot of a fascist dictatorship. See, for example, “Ron DeSantis Is All In—on Creating an American Autocracy” (Mother Jones):

His plan to outflank Trump would scale up the calculated system of repression he designed in Florida. …To stifle dissent, in 2021 DeSantis signed a law that would ramp up penalties for rioting but that civil rights groups warned would ensnare peaceful protesters [what about mostly peaceful protesters?]; this spring he pushed legislation to unleash speech-chilling lawsuits against news outlets.

DeSantis, like other distrustful autocrats, keeps a tight circle of advisers, including his wife.

One way DeSantis has created space to operate is by hollowing out state government, filling key posts with donors and loyalists—the academic term is “autocratic capture”—perhaps most notably on the state Board of Medicine, which has supported his agenda to put new limits on gender-affirming care.

Nobody would live in Florida, in other words, unless he/she/ze/they has no other option, e.g., is incarcerated or established in public housing that would take 10 years of waiting to get into in another state. Anyone who cherishes freedom should have driven north on I-95 in fall 2020 when DeSantis ordered public schools to reopen and refused to permit county and local officials to order lockdowns, masks, and vaccine injections.

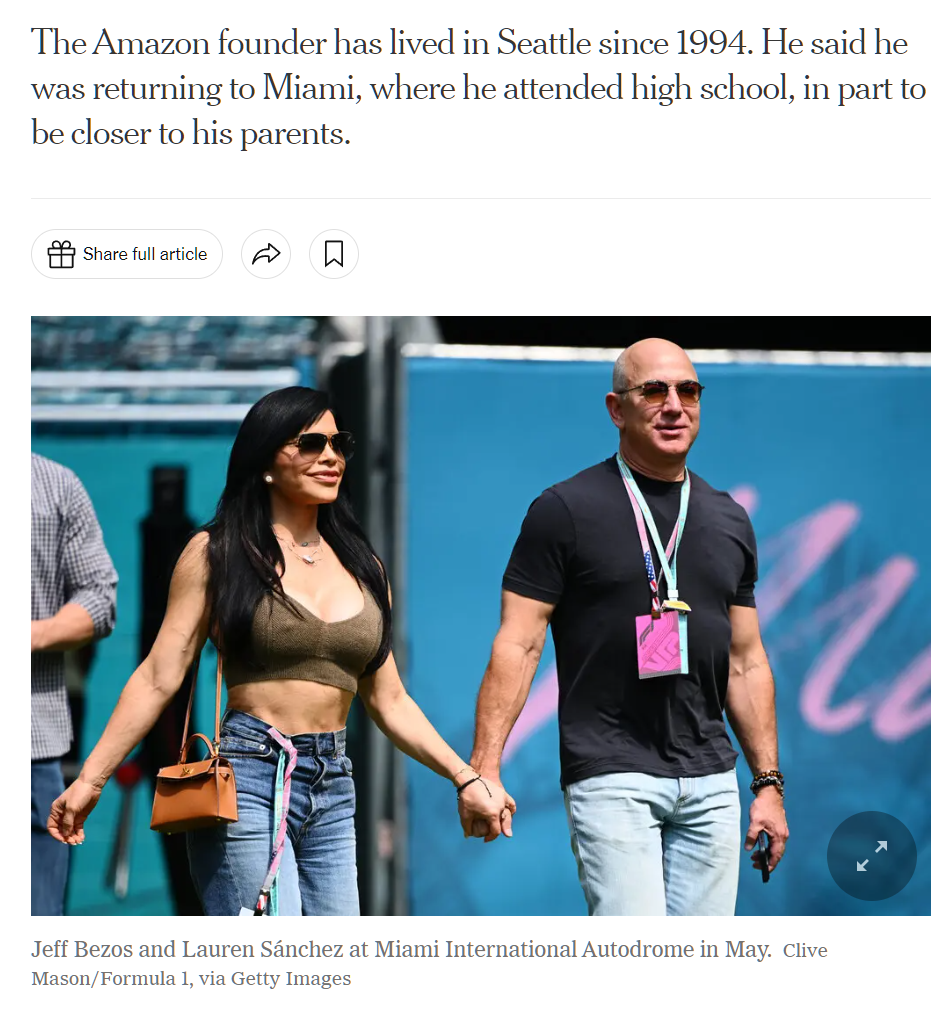

In Latinx migrant suffers from fascism and tyranny imposed by Governor Ron DeSantis, we looked at Lionel Messi apparently having no other choice for where to live. This month, the victim of tyranny is Jeff Bezos. “Jeff Bezos Says He Is Leaving Seattle for Miami” is the typically thorough New York Times article:

Mr. Bezos, 59, announced his move in an Instagram post on Thursday night. He said his parents had recently moved back to Miami, where he attended high school, and that he wanted to be closer to them and to his partner, Lauren Sánchez.

Another factor, he said, was that operations for his rocket company, Blue Origin, are increasingly shifting to Cape Canaveral, Fla., just over 200 miles by road north of Miami along the state’s Atlantic coast.

Bloomberg News reported last month that Mr. Bezos had purchased a mansion in South Florida for $79 million, a few months after buying a neighboring one for $68 million. Mr. Bezos is worth $161 billion, making him the world’s third-richest person, according to Bloomberg.

Mr. Bezos said in his Instagram post that he had “amazing memories” of Seattle and had lived there longer than anywhere else. “As exciting as the move is, it’s an emotional decision for me,” he wrote. “Seattle, you will always have a piece of my heart.”

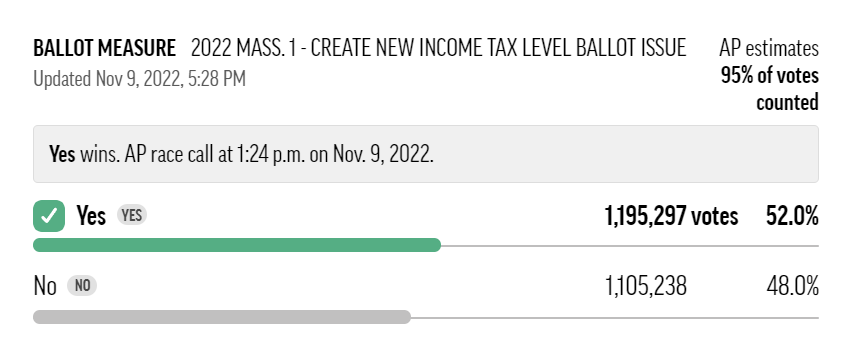

The fearless journalists uncritically accepted the “emotional” explanation and did not include the word “tax” anywhere in the article. What’s new in Washington State, historically a state that was free from any personal income tax? A 7 percent income tax on long-term capital gains (wa.gov), starting in 2022:

The 2021 Washington State Legislature recently passed ESSB 5096 (RCW 82.87) which creates a 7% tax on the sale or exchange of long-term capital assets such as stocks, bonds, business interests, or other investments and tangible assets.

This tax only applies to individuals. However, individuals can be liable for the tax because of their ownership interest in a pass-through or disregarded entity that sells or exchanges long-term capital assets. The tax only applies to gains allocated to Washington state.

Washington State also imposes a death tax of 20 percent on residents who were successful in life. Florida’s constitution bars both income and estate taxes.

Even if the new tax was not a factor in Bezos’s decision to move to Miami, the move will have a big impact on how much revenue the Covidcrats of Washington State will collect from the new tax and, therefore, what they can spend on social justice initiatives (“The Democratic Party controls the offices of governor, secretary of state, attorney general, and both chambers of the state legislature” (source)). It seems like a failure of what we used to call journalism that the New York Times didn’t mention the dramatic changes in the Washington State taxation landscape (first the new tax and second the moving out of the biggest taxpayer).

Related:

- Effect on children’s wealth when parents move to Florida (a calculation that kids can be about 40 percent richer if parents move from Massachusetts, who tax rates are actually lower than Washington’s)

- Back in 2021, the state held a public hearing on House Bill 1406, which concerns a proposed Washington state wealth tax, Sen. Noel Frame, D-Seattle remarked at that hearing that there is a “really pessimistic view of the world to just assume someone would leave [Washington state].” “These are folks who have been deeply invested in our community,” (source)

- The Myth of Millionaire Tax Flight, by Cornell sociologist Cristobal Young, pointing out that rich people won’t move in response to higher state taxes

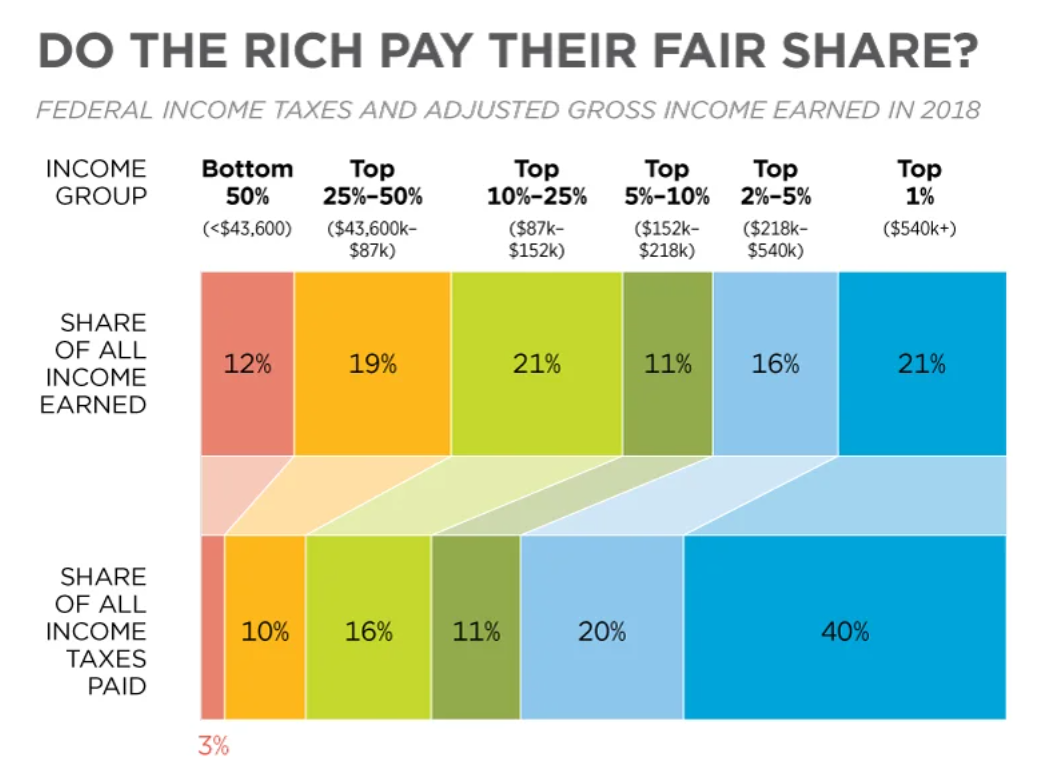

- “Lessons from Washington State’s New Capital Gains Tax” (by Kamau Chege; The Urbanist, June 2023): Taxing the rich works like a charm. … For decades, the wealthiest Washingtonians have gotten out of paying what they truly owe in state and local taxes. … One of the first lessons is that our state’s richest residents are much, much richer than we understood — and they are continuing to get richer at a faster rate than previously assumed. … working people know that private wealth is built on public infrastructure and public investments paid for by all of us — especially low-income folks who pay more than their share in taxes. … the richest people in our state, like Jeff Bezos and Bill Gates, have armies of accountants working to find tax loopholes and write-offs.

- “Capital Gains and Tax ‘Fairness’” (Editorial Board; WSJ, 2021): “The Biden and Olympia tax increases on capital gains won’t matter to Bill Gates or Jeff Bezos, who are already rich and can hire lawyers to shelter their future gains.” [Maybe the WSJ envisioned that Bezos would switch to borrowing against his stock? But that doesn’t work in a high-interest-rate environment.]

- “Victory! Bill to levy capital gains tax gets “do pass” recommendation from House Finance” (Northwest Progressive Institute, 2021): A substantial chunk of the revenue from the proposed capital gains tax would be paid by just two individuals: Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos, who are among the world’s richest men.

- cities ranked by sunshine (move.org): 73 percent of days in Miami vs. 46 percent of days in Seattle

- Ron Desantis’s latest outrageous position: