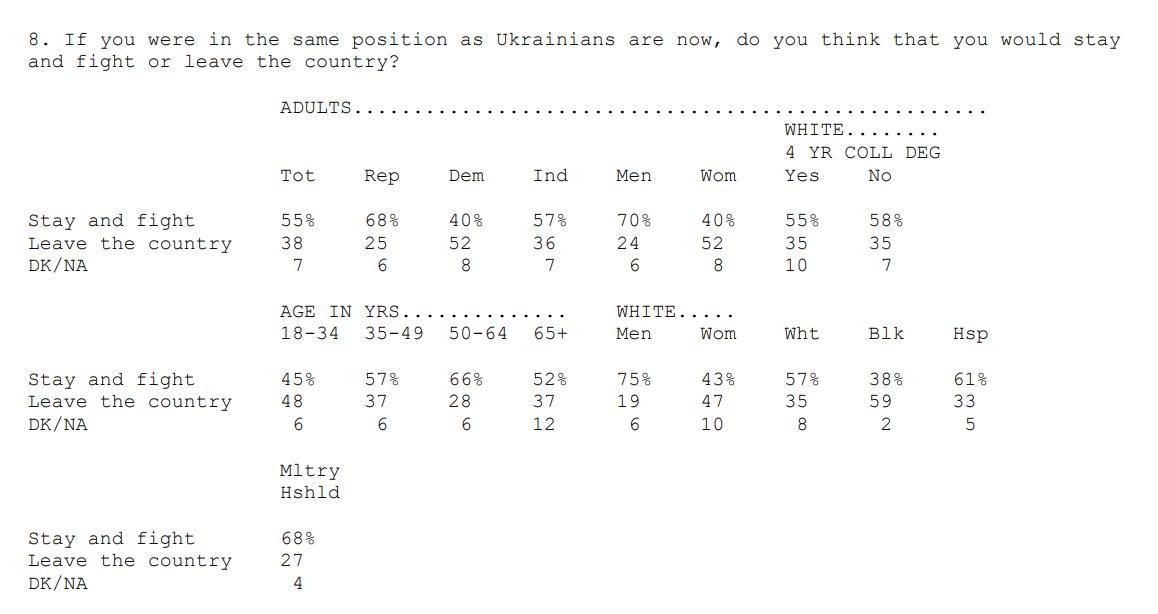

The situation in Ukraine is bewildering to those of us who received parochial American educations. The Wall Street Journal attempts to explain it in “Putin’s Endgame: Unravel the Post-Cold War Agreements That Humiliated Russia”:

The Russian leader is trying to stop further enlargement of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, whose expansion he sees as encroaching on Russia’s security and part of the West’s deception and broken promises. He wants NATO to scale back its military reach to the 1990s, before it expanded east of Germany.

In sum, Mr. Putin seeks to undo many of the security consequences of the Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991, an event the Russian leader has called the “greatest geopolitical catastrophe” of the 20th century.

Looking back, many current and former Western officials say it is clear that the U.S. and its allies handled relations with Moscow poorly in the 1990s, and that the triumphalism over winning the Cold War was excessive.

“Although I think that Western diplomacy was arrogant and incompetent in the 1990s, and we’re paying the price now, that is not a reason for Putin to put himself in a posture that makes other people think he’s about to launch a war,” said Rodric Braithwaite, who was British ambassador to Moscow when the Soviet Union collapsed.

Yet in 1994, Russia joined with the U.S. and U.K. in committing “to respect the independence and sovereignty and the existing borders of Ukraine” and “to refrain from the threat or use of force” against it, a security guarantee that helped persuade Ukraine to give up its nuclear weapons.

Where are the US and the UK today with their “security guarantee”? (See the Budapest Memorandum.)

A successful friend who grew up in Ukraine:

Overheard young Swiss on a chairlift:

Guy 1: All this stuff with Ukraine is crazy. If World War III happened, it would be kind of cool. But also kind of not cool.

Guy 2: Yeah, it would not be. But you know, if we [Switzerland] manage to repeat what we did in WW2, we should be fine.

An American on the European response (putting the amazing new undersea pipeline on hold):

Man the Germans are sticking it to Putin. They are only going to buy half of their natural gas from him.

A Deplorable American with a Ph.D. in biology:

New sanctions are going to be about as effective against Putin and Russia as cloth masks were against the coronavirus.

From an aircraft mechanic:

If Putin takes over the Ukraine does Hunter still get his board of director payments?

An American passionate about free speech:

I am curious to see how long it takes for Twitter to suspend Putin’s account for spreading misinformation. Or does suspension apply only to “mean tweets”?

One question is whether the 44 million people who live in the Ukraine can qualify for asylum in the U.S. A person who says “my spouse is hitting me” qualifies for permanent residence in the U.S. and, if he/she/ze/they does not wish to work all that much, a lifetime of associated means-tested subsidies for housing, health care, food, and smartphone. As fearsome and difficult to escape as a domestic partner might be, a shooting war involving the powerful Russian Army is surely scarier. (Note that the New York Department of Health actually spends more than what the Russians spend on their entire military.)

I asked a friend who gets a paycheck from the refugee-industrial complex what would stop all 44 million Ukrainians from going to Mexico, walking across the Rio Grande, and saying “I request asylum”. His response:

They might qualify, but due to Trump policy that courts have not let Biden rescind, asylum seekers are being sent back across the border to wait in Mexico. Supreme Court recently agreed to hear the case. They might have a better chance of getting asylum if flew into NY on a tourist or other visa and then got a lawyer and filed asylum claim.

Me: “I don’t see how one can argue that Ukraine is not a dangerous place to be right now.”

Covid rule is different. That’s called “Title 42” and allows for immediate deportations due to health crisis. It also depends which city your hearing is held in. Rate along southern border is much lower than in NY. And if you have a lawyer, about 10x better chance. I would agree those fleeing Ukraine have a decent claim, but you’d still have to convince asylum judge. Being a political dissident or member of religious minority is better than just saying “I’m scared of war”. If Russians or Separatists declare that they’re looking for you that would help. You need to be able to convince a judge that you have a reasonable fear of persecution. Asylum seeker must show that they have a “well-founded fear of persecution in their home country on account of either race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group.” That’s the legal principle.

He pointed out that Temporary Protected Status would also be an option for Ukrainians who wished to be far away from any armed conflict.

Haitians had it after earthquake.

(“Temporary” for Haitians began in 2010 and was recently extended to at least 2023. Children born in the U.S. in when “temporary” began are now biologically capable of having children themselves.)

The question of 44 million Ukrainians being entitled to come here makes me wonder a bit about what kind of society the U.S. is building by giving immigration priority to those who say that they are at risk of being attacked somewhere else. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, for example, people migrated to the U.S. because they liked the idea of living in the U.S. Now we are filling the U.S. to a Chinese/Indian density with people who say that they don’t want to live wherever they’ve been living. It isn’t that they are attracted to what they perceive as American cultural values, for example, but they are repelled by threats against life and limb wherever they are. They might find American cultural values, such as hatred of Asians and discrimination against Blacks and those who identify as “women”, abhorrent, as Eileen Gu does, but living in the U.S. is nonetheless preferable to suffering inescapable domestic or gang violence in their home countries.

Full post, including comments