History of Huawei (II)

A second post about the core topic within House of Huawei: The Secret History of China’s Most Powerful Company …

How does hiring and firing work in a company that isn’t passionate about DEI?

On January 28, 1996, Ren Zhengfei held Huawei’s first “mass-resignation ceremony.” Each head of a regional sales office was told to prepare two reports: a work summary and a written resignation. “I will only sign one of the reports,” Ren said. “Dear Chairman,” the resignation letter said, “I have fought for the company’s sales development and sacrificed my youth. But in the few years that I’ve worked on the sales front lines, my technical and business ability may not have kept up…. If through the process of examination and selection, the company identifies a more suitable person for sales work, I will sincerely resign from my current position.” Huawei had started out in rural markets, and many of its early sales managers were provincial in their experience and network of contacts. As Ren sought to go national and international, he decided to make the entire sales staff resign and reapply for their jobs. “The mountain goat must outrun the lion to not be eaten,” he had told them ahead of the event. “All departments and sections must optimize and eat the lazy goats, the goats that do not learn or progress, and the goats with no sense of responsibility.” Now Ren took the podium. “Being an executive at Huawei should be understood as a responsibility, a choice to sacrifice personal happiness,” he said. The resigning sales managers were allowed to speak in turn, some choking back tears. “As a Huawei person, I’m willing to be a paving stone,” one said. “If I can’t keep up with the pace of the company’s development, I’m willing to let new people, and higher-level people, take over my job,” another offered. “My youth and ability are limited, and Huawei’s future is long,” a third said. “I can’t hold back the company because of me.”

Maybe sales will be one of the few jobs left to humans after Elon Musk gets Optimus to do everything?

Ren had grown up in the Mao years, when there was no such thing as private-sector sales. Now he presented sales to his young followers in rousing terms, almost as a mystical vocation. “Sales work is special, complex, and noble,” he told them. “You need the intelligence of a scientist, the insight of a philosopher, the eloquence of an orator, the ambition of a social reformer, and the optimism and persistent spirit of a religious man.”

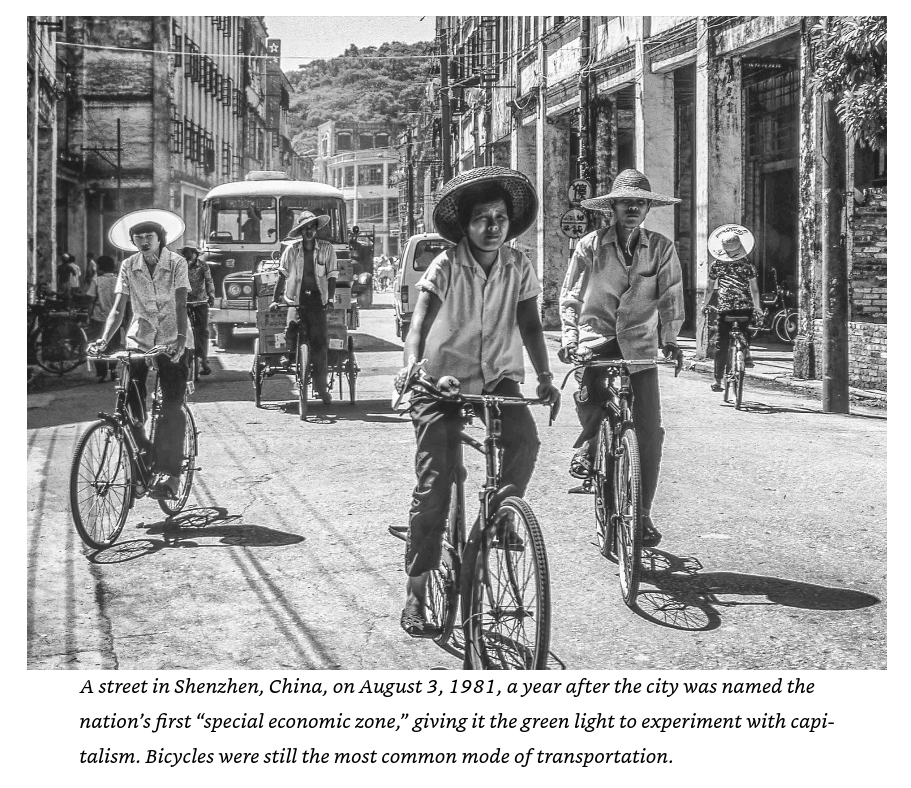

Polite protocol for a business dinner involved breaking out the baijiu, a clear sorghum spirit that has an eye-watering 120-proof kick, and pouring out round after round of shots over a rotating parade of exquisite dishes. The protocol also involved getting drunker than your clients to show your respect for them. One early Huawei executive wrote about having to excuse himself for a vomit break while entertaining customers—not an uncommon occurrence. Others developed stomach or liver ailments. This seemed to happen particularly often in the far northeast, which had a reputation for heavy drinking. “The key staffer for this account is currently suffering hepatitis but refuses to come back to Shenzhen for medical treatment and insists on fighting on the front line through the ice and snow,” Ren said in 1995 about a Huawei salesperson based in Yichun, close to the northeastern border with Russia.

The story of Huawei is definitely not as simple as “it was a planned economy and the planners picked Huawei”:

Despite the interest that Huawei had received from government officials, it was only one among many contenders, and not even the most favored one. In 1995, officials had set up a state-owned switchmaking champion called China Great Dragon Telecommunication in an effort to combat the foreign switchmakers. Great Dragon was built around the military engineer Wu Jiangxing’s breakthrough 04 switch and had been formed by merging eight smaller telecom companies. The government was pouring some $2.2 billion a year into the venture. Also in 1995, the Xi’an Datang Telephone Co.—a venture set up by a state-run research institute and several Chinese graduates from US universities—began mass production of its new switch, the SP30. And across town in Shenzhen, the Zhongxing Telecommunications Equipment Company—which would later be known as ZTE—had developed its ZXJ10 switch. People called them the Big Four of China’s domestic switchmaking, and they made quick work of eating into the foreign vendors’ market share. Within a few years, the price of telephone switches in China had dropped from $300 per line to $70 per line. With so many contenders, and such thin margins, companies were always flaming out. In early 1996, a dozen of Great Dragon’s 04 switches abruptly failed due to a software problem. The company never recovered.

Huawei had started out as an underdog compared with its state-owned rivals. Now it was emerging as the frontrunner, so much so that the state-owned companies were crying foul. “They sell cheaply to get market share,” an executive at Datang complained. Great Dragon’s Wu Jiangxing griped to Shenzhen’s Science and Technology Bureau that the local government shouldn’t just support privately owned companies.

Despite the shortage of PhDs in DEI in China and overt sexist sentiments, women are able to rise to top executive positions.

The executive who rose the highest was Sun Yafang, who was elevated from marketing and sales president to Huawei’s vice-chairwoman in 1994. She was an intense woman of around forty, with a hawkish nose and a stately bearing. She had overseen Huawei’s “marriage” to the state through the joint ventures with provincial telecom bureaus and had led the mass resignation of the sales managers. People whispered that Madam Sun had worked for the Ministry of State Security, or the MSS, China’s powerful civilian intelligence agency, before joining the company. Perhaps that had something to do with her rapid rise through Huawei’s ranks, or perhaps not.

Sun ran a tight ship, cracking down on excessive golfing among the managers. “Huawei’s sales staffers all know that if Madam Sun sees you without a tie on a convention floor, your fate will be a miserable one,” a member of her team wrote about her. “Not to mention her fiery temper. The hurricane of her criticism will leave you with no possible hope to find an escape.”

Ren had proved willing to promote capable female executives, even as he sometimes expressed old-fashioned views on women in the workplace. “Many companies don’t like hiring female employees, because female employees are inefficient and can’t achieve the goals when they do things,” Ren said in a speech to Huawei’s secretaries around this time. “Female employees have a big shortcoming, which is they like to gossip and nag, which undermines unity. Originally, the purpose of hiring female employees was to add a lubricant to the management team. The main characteristic of male employees is their rigidity, and they are prone to producing sparks when they collide. With a layer of elastic sponge in between, there won’t be sparks.”

A lot of Huawei’s management and corporate practices were modeled on IBM’s and with IBM consultants’ help:

IBM’s consultants started arriving at Huawei’s headquarters in August 1998. They would remain in residence for a decade. Gary Garner, one of the early IBM consultants, recalled that his first impression of Huawei was that it was a vibrant but undisciplined company where things were sometimes just scrawled on sticky notes instead of being filed properly. “President Ren had a whole bunch of bright young PhDs,” he said, “but it was disorganized. It wasn’t ready to go to the international market.” Some of Huawei’s managers protested the new systems, which they found burdensome. Ren insisted they follow the IBM way. If the shoes didn’t fit, Ren told them, they had to “cut their feet to fit the shoes.” IBM’s output was fifty-five times Huawei’s that first year, 1998. Ren set a goal of shrinking the difference to thirty-five to forty times greater by 1999. “We are making big strides forward,” he told his staff. “We’re narrowing the gap.”

One place that Huawei didn’t follow IBM was onto a public stock exchange. The company remains privately owned, mostly by employees, to this day.

Imagine if U.S. politicians would follow Ren’s example of voluntary semi-retirement at age 67:

In December 2011, Ren, sixty-seven, announced he was stepping back to allow younger hands to steer the company. “I increasingly don’t understand the technology, increasingly don’t understand finance, and only half understand management,” he told his staff. “If I can’t treat our group kindly and democratically, and fully unleash the talents of all our heroes, I will have achieved nothing.”

Much of the rest of the book is about Huawei’s entries into various foreign markets and tussles with the U.S. and other Western intelligence agencies that either (1) wanted a back door to tap into communications, or (2) were worried that their Chinese counterparts had a back door into Huawei’s gear. I won’t cover that here because it is too involved, but I will have another post about this House of Huawei: The Secret History of China’s Most Powerful Company.

Full post, including comments