I caught up recently with my source for “Fast-food economics in Massachusetts: Higher minimum wage leads to a shorter work week, not fewer people on welfare”. He owns donut shops and, following minimum wage hikes, had workers asking for their hours to be cut so that they could continue to be eligible for various forms of welfare, including means-tested housing and health insurance subsidies.

What’s going on during coronaplague? “Business is down 50 percent,” he replied. “But we should be able to get a loan from the government that will pay for two months of salaries.”

What’s the main challenge right now? “Almost all of my workers could make more collecting unemployment than by continuing to work for me,” he said. This has created a delicate situation. Given that unemployment is now more lucrative than full-time work, does he lay off the best workers, rewarding them financially for their high effort and dedication to his business? Or does he lay off his least productive workers, thus inadvertently rewarding them financially for their weak efforts and lack of dedication?

How about around the rest of the neighborhood? Other than the supermarket, our town has one source of food that remains open: a pizza and sub shop that has a few tables, but was always primarily a take-out business (it occupies half of a gas station). The owner-chef says that business is down 60 percent.

Readers: Are you as surprised as I was by these numbers? Most donut sales are drive-through and/or takeout to begin with. Wouldn’t people want to escape their houses, enjoy a traffic-free 5-minute trip to the local donut shop, and come back with a delicious coffee and donut? And why are pizza/sub sales down? I have a tough time believing that our neighbors have finally learned to use their $250,000 dream kitchens.

A neighbor is an accountant for small-to-medium-sized businesses here in Massachusetts. He reports that every employer with whom he works is besieged by employees, especially the part-time and low-wage ones. Are they nervous about the future of the economy and want extra hours and overtime pay so that they can save up? No. Like the donut slingers, they want to be laid off because they can achieve a similar or higher spending power by collecting conventional Massachusetts unemployment plus $600 per week from the Federales.

Consider someone who works 25 hours per month at $20 per hour, helping out a retail store during busy hours. That’s $500/month, which would entitle the worker to roughly $200/month in benefits in the event of a layoff. Right now, however, unemployment will pay closer to $2,800/month.

How about a full-time minimum wage worker? Let’s call that 172 hours times $12 per hour = $2,064 per month. Unemployment will pay over $3,000 per month.

I met a 24-year-old who works for a national retail chain that is headquartered in Massachusetts. She has been cut from five days per week in the office to two days per week working from home. “I hope this lasts through the summer,” she said. “I’m making at least $200 extra per week while hardly doing anything.” (She has a 24-year-old friend, meanwhile, who has been terrified by reports of young people cut down by Covid-19. The slender healthy young person will not leave her apartment.)

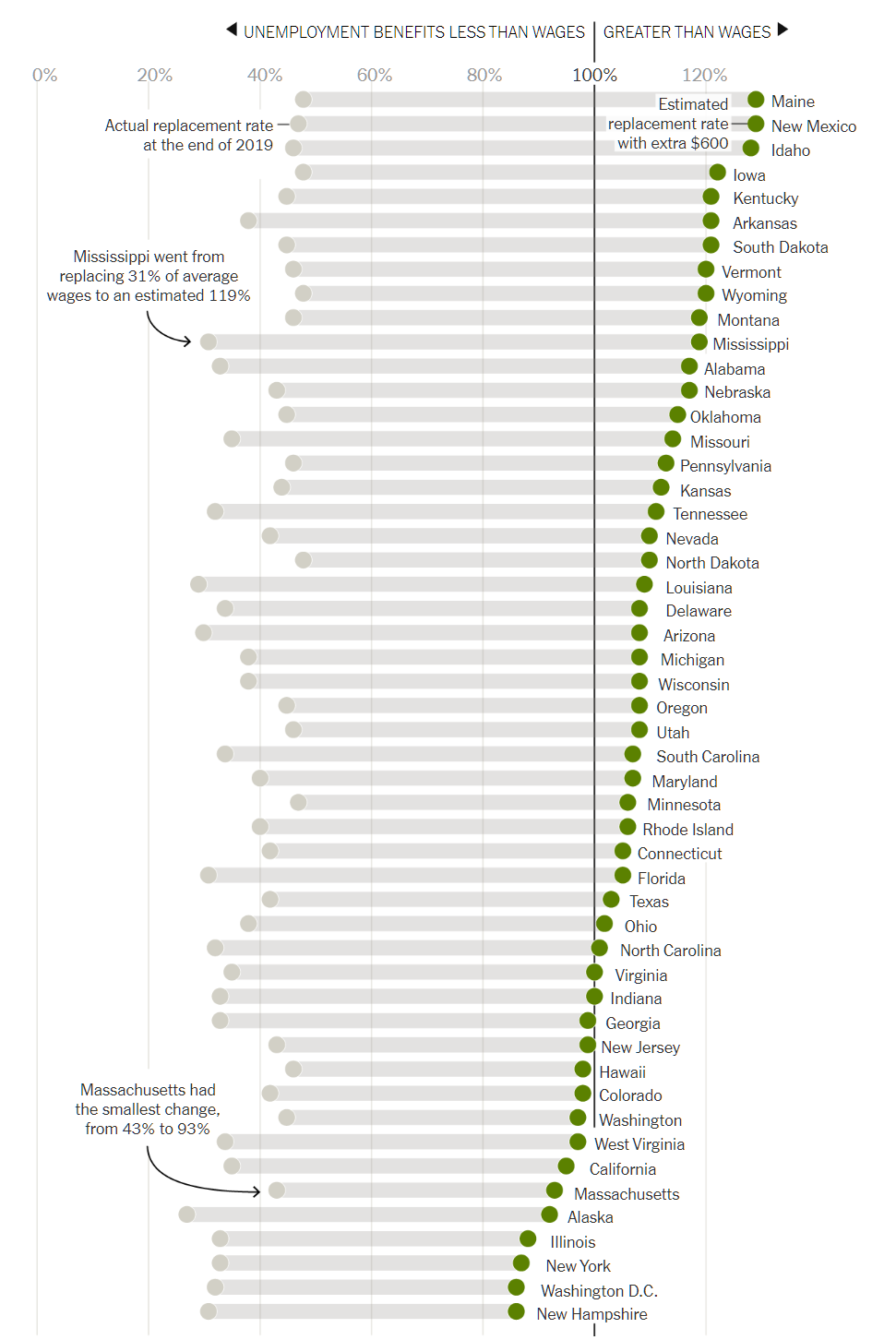

How typical are these experiences in which an employee actually has a higher spending power by being laid off? “The $600 Unemployment Booster Shot, State by State” (nytimes) says “Workers in more than half of states will receive, on average, more in unemployment benefits than their normal salaries”:

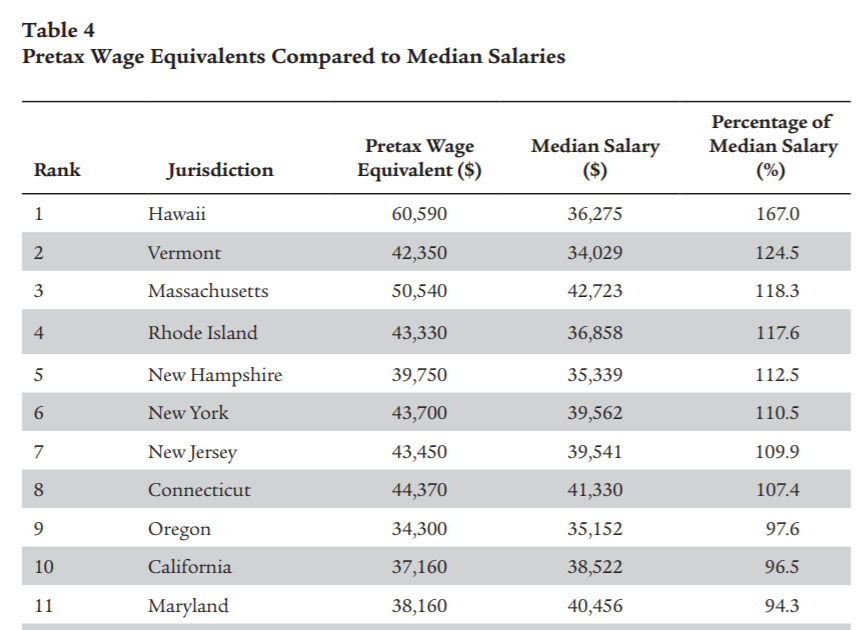

It looks as though there are some strange bedfellows in this table. New Hampshire and New York, for example, are two of the states that offer the highest reward for continuing to work (still a minimal difference in spending power compared to playing Xbox and watching Netflix all day).

One of the main themes of the Bell Curve (1994) is that American society becomes more unfriendly each year to those whose IQ is below average. I wonder if this is being amply proven by the current landscape of work-versus-welfare alternatives. The Bell Curve says that in the old days it wasn’t that helpful to have a high IQ. If you were born a peasant you could think big thoughts while digging for potatoes. It wasn’t that harmful to have a low IQ. If you worked harder you’d get paid more. If you committed a crime, of which there was a short list of easily understood prohibitions, you’d get imprisoned. Our modern world, on the other hand, has thousands of crimes, many of which are non-obvious and/or not regularly punished. Would a person with an IQ of 90 be able to figure out that saying “I didn’t do it” to a law enforcement officer could result in 5 years in prison (Brogan v. United States), more than pleading guilty to killing a fiance in order to get the insurance cash?

Pre-plague Massachusetts already presented a non-obvious landscape for planning out a life of earning. Having a child and living on welfare yields a greater spending power than working at a median wage job (CATO analysis). Having sex with a married dermatologist yields a greater spending power than going to medical school and working as a primary care doctor (our family law). Having sex with three different already-married above-median-income partners and collecting child support from each yields a substantially greater spending power than marrying a median-income partner. Add to all of these we now have a situation in which workers are much better off financially being fired than continuing to work. And, of course, they’re also way better off in terms of exposure to the dreaded coronavirus if they stay home and play videogames or watch TV.

We have a similar situation for business owners. The smartest and most successful business owners had their free government cash arranged within days. They had no trouble figuring out which bank to use, what forms to fill out, etc. (The biggest banks helped the biggest customers, taking advantage of the fact that a hotel or restaurant chain with 100 directly owned locations was considered 100 “small businesses” rather than one big business.) The honest, but not-too-bright, small business operator? He/she/ze/they was mostly out of luck.

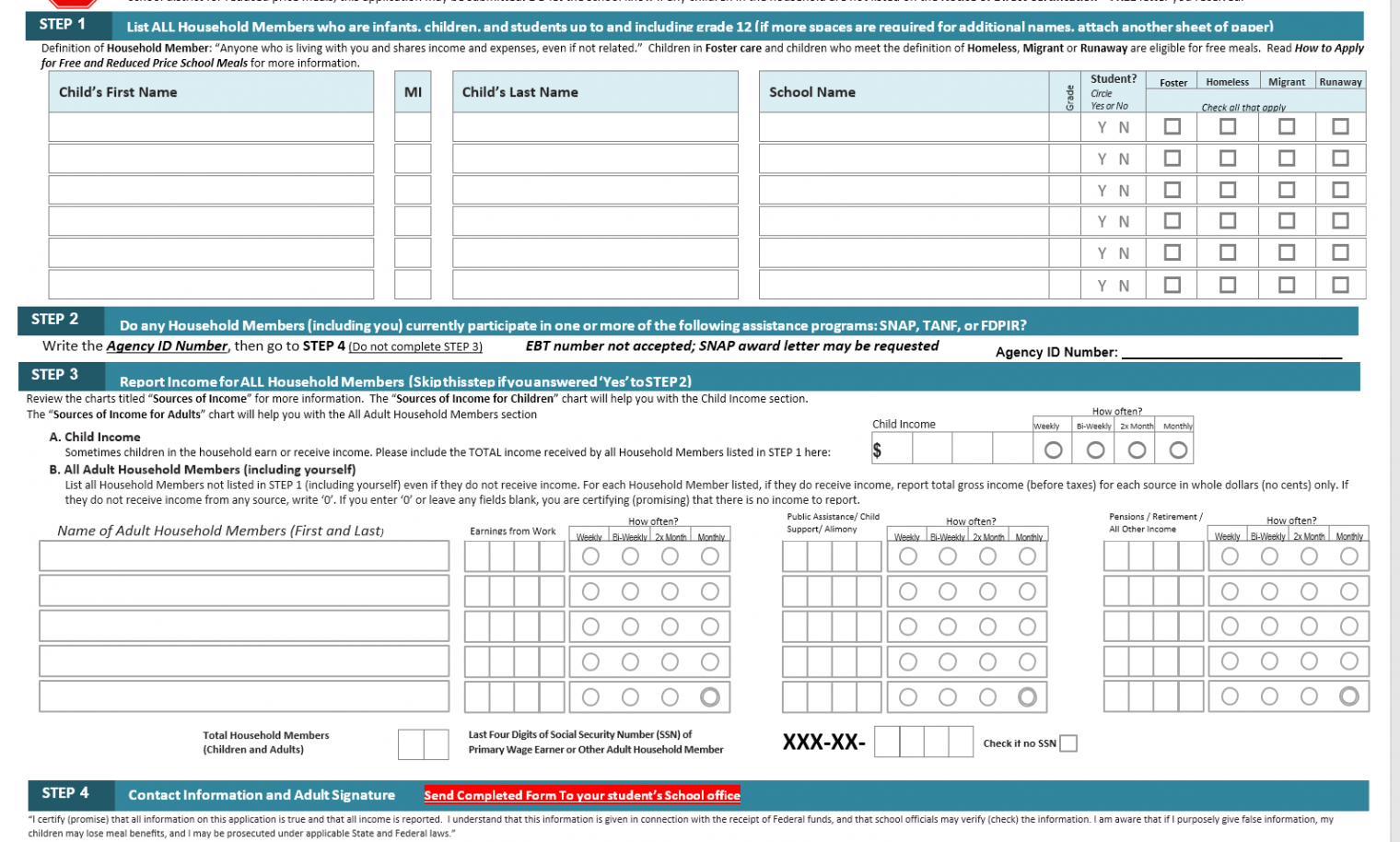

How about people who want to collect conventional welfare? Here’s part of an email from our local school:

The events of the COVID-19 emergency may have changed financial circumstances for your family. As a consequence, your students may now be eligible for the Free and Reduced Price School Meals (FRL) program. If they are eligible for the FRL program, the national Pandemic-EBT program may provide additional benefits in the form of food assistance cards.

Details of the Pandemic-EBT program may be found at https://www.mass.gov/info-details/pandemic-ebt-p-ebt. It is a supplemental program provided through the Massachusetts Department of Transitional Assistance. Eligibility is based on the FRL status, so, if your family circumstances have changed, you may wish to apply for enrollment in the Free and Reduced Price School Meals (FRL) program.

The application form is attached. You may fill out the Word document and upload the completed application file electronically to the Free & Reduced Lunch Application Submission Folder. That is the preferred application method. You could also print out the PDF version, fill it out, sign, and scan it, then upload it electronically to the Free & Reduced Lunch Application Submission Folder. Either method provides for the confidentiality of your information.

So… as long as you have a scanner and/or an Office 365 subscription, free meals will be coming your way! Here’s an excerpt:

Confusing: Each of your six children can be “foster”, “homeless”, “migrant”, and/or “runaway”. If a child has run away, however, how would there be an adult filling out this form?

(The form also says “We are required to ask for information about your children’s race and ethnicity. This information is important and helps to make sure we are fully serving our community.” Dare we ask if the white poverty industry employees will try to prepare ethnically appropriate meals for each child? It will like Clint Eastwood in Gran Torino trying to make Hmong meals for the neighbors?)

Is this truly accessible to a person with a below-average IQ?

Full post, including comments