New York Times: Cash-strapped consumers get “relief” via higher prices

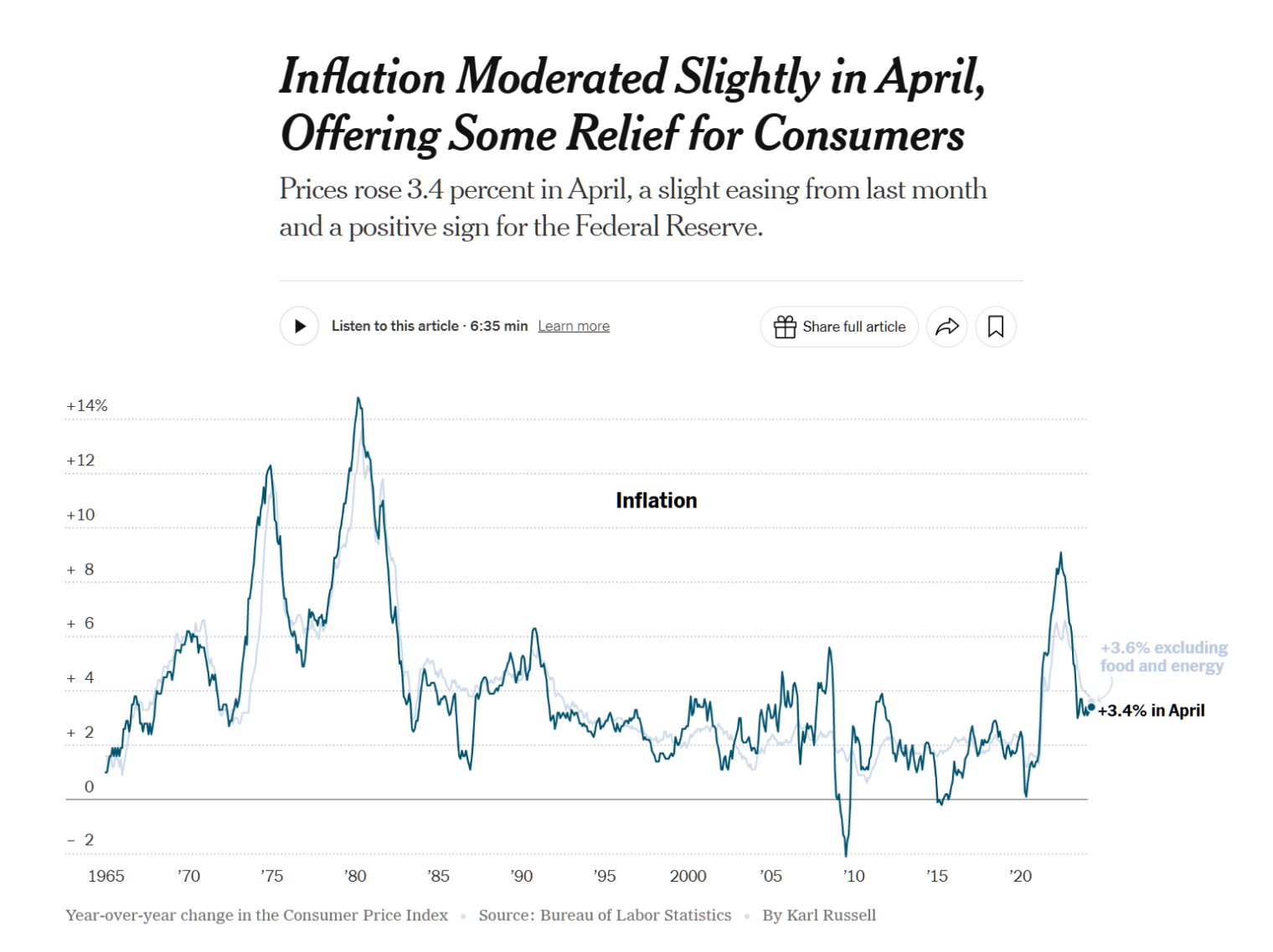

“Inflation Moderated Slightly in April, Offering Some Relief for Consumers” (NYT, May 15):

The Consumer Price Index climbed 3.4 percent in April from a year earlier, down from 3.5 percent in March, the Labor Department said on Wednesday. The “core” index — which strips out volatile food and fuel prices in order to give a sense of the underlying trend — rose 3.6 percent last month, down from 3.8 percent a month earlier. It was the lowest annual increase in core inflation since early 2021.

The report followed three straight months of uncomfortably rapid price increases that rattled investors and worried policymakers at the Federal Reserve. Economists cautioned that one month of encouraging data was far from enough to put those worries to rest. But they said that the data should ease concerns, at least for now, that inflation is re-accelerating.

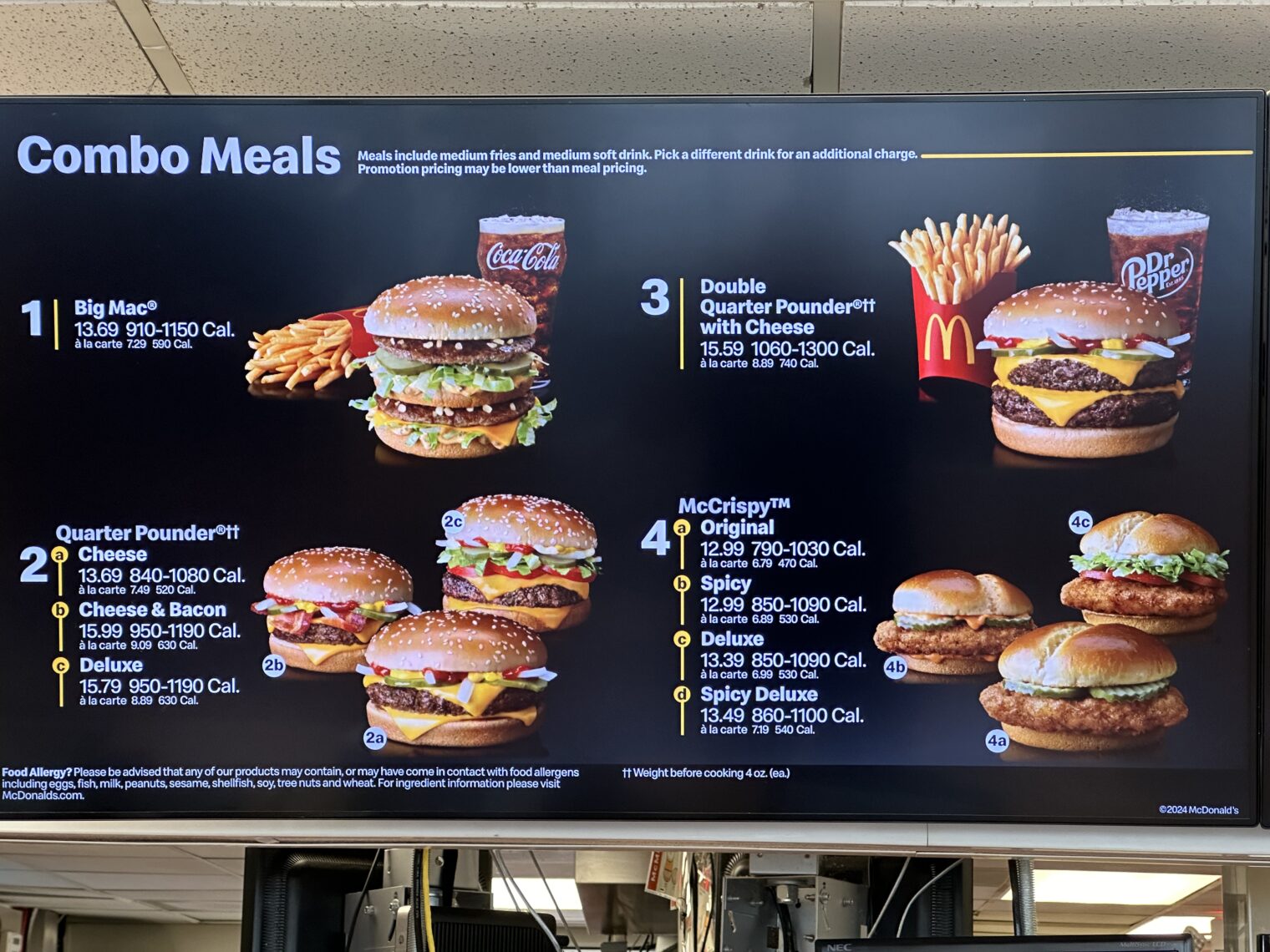

If you couldn’t afford stuff previously, therefore, you’ll be “relieved” to learn that prices are yet higher.

Even more confidence-inspiring… an 81-year-old who never took an economics class is tackling what non-NYT readers might perceive as a problem:

“I know many families are struggling, and that even though we’ve made progress we have a lot more to do,” Mr. Biden said in a statement released by the White House. He called bringing down inflation his “top economic priority.”

If you don’t like higher prices, it’s “progress” when prices are higher every month. Maybe it doesn’t matter that the president hasn’t taken economics because he/she/ze/they is advised by expert economists? Let’s look at the chair of Joe Biden’s Council of Economic Advisors:

Bernstein stated he grew up in a “musical family” and aspired to be a professional musician as a young person. Bernstein graduated with a bachelor’s degree in music from the Manhattan School of Music where he studied double bass with Orin O’Brien. Throughout the ’80s, Bernstein was a mainstay on the jazz scene in NYC.

He also earned a Master of Social Work from Hunter College as well as a DSW in social welfare from Columbia University’s school of social work

(He’s so old that he could get to class at Columbia without pushing through a thicket of tents and Palestinian flags!)

The NYT deceptively charts CPI since 1965 without noting that the definition has changed dramatically over this period. The reader is left with the impression that things were far worse during the Jimmy Carter “malaise years”:

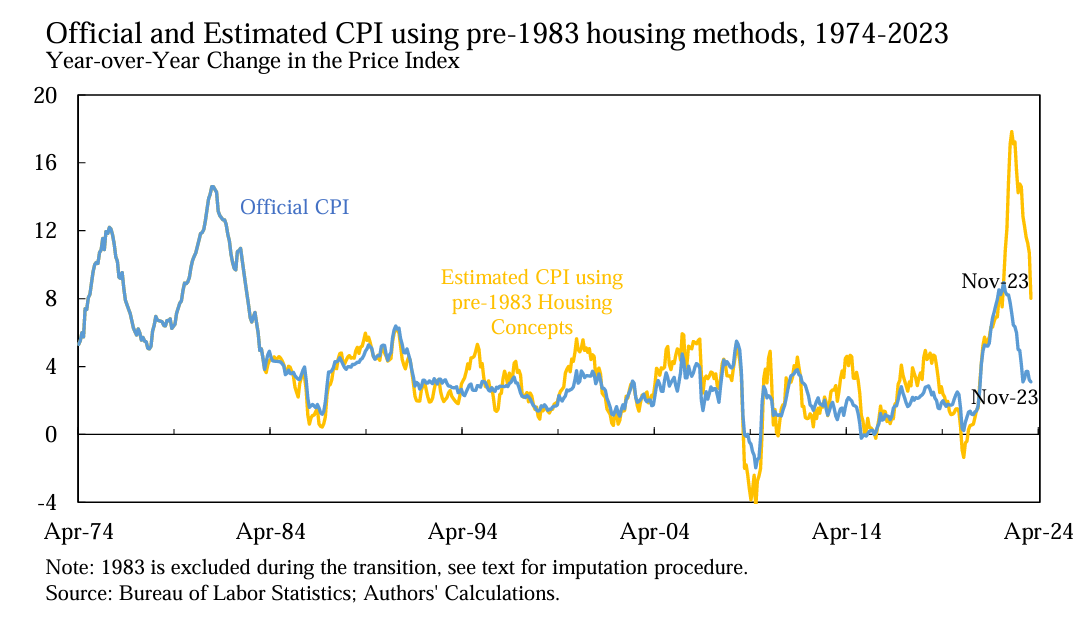

Larry Summers and friends, though, show us what the chart would look if you simply undid the big change from 1983 to use a fictitious rent measure rather than actual housing costs. In fact, Bidenflation is roughly comparable in intensity to the inflation that Americans suffered as a consequence of the Kennedy/Johnson expansions of the welfare state and the Kennedy/Johnson decisions to enter the Vietnam War (Carter gets blamed for this, but the seeds were sown in the 1960s).

Mostly I find the above fascinating as an example of journalism that purports to be neutral and skeptical yet in fact is primarily propaganda about the great job that our rulers are doing.

Full post, including comments