When the U.S. was founded, minimum voting age was 21. A man might start work at age 13 or 14 and therefore a voter would be someone who’d worked for 8 years and who would experience higher taxes and a bigger government as a requirement to work longer hours. Since 1972, however, the 26th Amendment has ensured that 18-year-olds can vote and an 18-year-old may not begin working full time for 10 years (or ever, if he/she/ze/they has figured out that welfare yields a similar spending power). The majority of voters either work for the government or don’t work at all (too young, too old, in “means-tested” living (not “welfare” since it is only housing, health insurance, food, and smartphone that are received rather than cash), collecting alimony or child support from a defendant worker, married to a worker). So the big surprise is that this majority hasn’t voted itself a vastly larger government to be paid for by private sector suckers who will have to work longer hours.

(Imagine how different our government would be if, except for the disabled, 8 years of full-time work history was a requirement to vote!)

There have been three major episodes in U.S. history when the voters hungry for more government benefits prevailed over the beasts of burden (folks for whom the main consequence of bigger government will be longer hours). One was in 1930s (FDR and the New Deal). One was in the 1960s (Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society, though arguably started by JFK). One was in November 2020. If we think that Episode 3 will be a lot like Episode 2, it is worth reading Great Society: A New History a 2019 book by Wall Street Journal reporter turned economic historian Amity Shlaes. I’m just digging into this, but the author seems to have anticipated our current situation (Episode 3). She looks at what happened to last the time that the U.S. decided to “go big” on addressing inequality. The economic and stock market stagnated while the dollar fell and gold surged. If Shlaes is right, every Federal spending initiative is great news for Bitcoin investors.

Some excerpts:

As Stalin was said to have joked, America was the only country in the world that could afford communism.

In a recent book the author had itemized the kinds of reform America needed. Laws that backed up organized labor so it might represent a greater portion of the American workforce, including black Americans or immigrants from Mexico. Higher minimum wages—the current levels were a cruel joke. Minimum wages that covered more workers, even those who did not work in an office or full-time. A dramatic change in the training of bigoted policemen in the big cities. A reinvigoration of the poor so that they became a force in political life. America was a country made of classes, the author thought; it just didn’t know it. The money was simply in the wrong hands. The writer wanted a tax system that captured the elusive wealth of the superrich. The moment had come to level incomes in a systematic fashion. Poverty was the obvious lunch theme. Just days before, the president had tapped the author’s host to lead a new campaign against poverty. In his State of the Union address, the president had told the country he wanted not only to alleviate suffering but to actually “cure poverty.” No American leader had ever taken on poverty in this way before.

The focus of the author’s book was the cycle of poverty in one region, Appalachia. The man had also seen poverty in the city where he grew up, St. Louis. In St. Louis the poverty was in part caused by government plans gone wrong, as in the case of the bulldozing of streets people loved in the name of moving them into public housing slums they didn’t love. America, the author thought, should invest billions to abolish poverty. It was incredible that America knew so much about poverty and had done so little. The state governments could not do this work. State governments were beholden to retrograde conservative legislatures. For systemic change, the author had come to believe, there was “no place to look except toward the federal government.”

Still, as he sat in the makeshift offices, the author kept returning to what he saw as the problem behind the problem, American capitalism. He and his friend took to concluding their memos with a half-serious line: “Of course, there is no real solution to the problem of poverty until we abolish the capitalist system.”3 At one point the author stopped censoring himself and wrote a few lines of what he actually felt: “that the abolition of poverty would require a basic change in how resources are allocated.” The boss actually took this bold call for redistribution to the president, who, the boss reported, proved remarkably friendly. The boss said that the president, a Roosevelt fan, told him that if serious economic redistribution was necessary to realize the long-delayed completion of the New Deal, then redistribution might be worth it.

The president being pitched on what today we might call transferism was Lyndon Johnson and the year was 1964. The author was Michael Harrington, whom Wikipedia describes as a “democratic socialist.”

The economic boom that had preceded JFK’s election gave Americans the confidence that anything was affordable. (I’ve seen this among quite a few folks in my parents’ social circle. Born in the 1930s, they don’t agree with Margaret Thatcher that it is possible to run out of other people’s money. They imagine the U.S. to be so wealthy that no spending proposal could ever exceed Americans’ ability to pay.)

Most Americans shared something else with Harrington: confidence. In the 1930s, the New Deal had failed to reduce unemployment. The prolonged periods of joblessness were what had made the Depression “Great.” But the memory of the New Deal failure had faded just enough that younger people liked the sound of the term. And memories of more recent success fueled Americans’ current ambition. Many men were veterans. They had been among the victorious forces that rolled across Europe and occupied Japan at the end of World War II. Compared with overcoming a Great Depression, or conquering Europe and Japan, eliminating poverty or racial discrimination had to be easy. American society was already so good. To take it to great would be a mere “mopping up action,” as Norman Podhoretz, who had served in Europe, would put it.

First came a campaign, led by President John F. Kennedy, to rehabilitate troubled youth. Soon after, President Johnson led the passage of series of federal civil rights laws. Around the same time came Johnson’s War on Poverty. Next were Johnson’s national housing drive and his health care drive. Richard Nixon followed up with a guaranteed-income campaign and an environmental drive.

When government accomplishes little, how do you persuade the public that enormous achievements are occurring?

Ambitious reforms needed time to succeed. It would be a shame if a project aborted because early results didn’t look good. So, for display purposes, presidents emphasized inputs, not outputs. Congress, too, as the Hoover Institution’s John Cogan has put it, “measured success by labels and dollars attached to legislation”—not by results. The political success of a project mattered more than empirical success. Occasionally, the effort got a new name. The “New Frontier” of Kennedy became Johnson’s “Great Society,” which became the “Great Nation,” and then the “Just and Abundant Society” of Richard Nixon.

We hear a lot about the various $2 trillion spending plans, but we never see a New York Times article on what Americans actually got from the preceding $2 trillion spending program. (exception?)

How did the dreams of the 1960s play out?

… by 1971, for the first time, federal spending on what we now call entitlements—benefits for the aged, the poor, and the unemployed, along with other social programs—outpaced spending on defense.

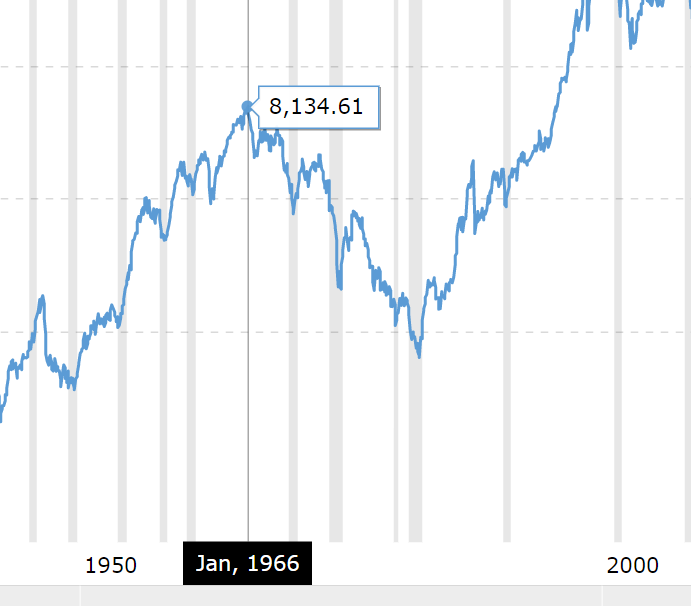

In 1966, the [Dow Jones Industrial Average] moved tantalizingly close to the 1,000 line, a landmark. Soon after, however, the index stalled, and stayed stuck below the 1,000 line, year in, year out. By the end of the decade, inflation, always present, was expanding to alarming levels. The same period brought another alarm, this time from abroad. Foreign governments started to turn more of their dollars in for gold from the United States’ coffers. The U.S. papers went into denial, quoting a Yale professor, Robert Triffin, who argued that the withdrawals were the result of crossed incentives in the international monetary arrangement, a technical, rectifiable flaw. What came to be known as the Triffin dilemma provided a convenient explanation for the mysterious outflows.

The 1971 run on American gold also, however, reflected foreigners’ insight. Outsiders knew a tipping point when they saw one. America had moved closer to Michael Harrington’s socialism than even Harrington understood. The United States had locked itself into social spending promises that might never be outgrown. Today, interest in Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies serves as a measure of markets’ and individuals’ distrust of the U.S. dollar. In those days there was no Bitcoin, but gold played a similar role. The dollar was the common stock of America, and foreigners used gold to short it.

The disastrous performance of the U.S. economy in the following years proved the foreigners’ 1971 wager correct. To pay for its Great Society commitments, the U.S. government in the next decade found itself forced to set taxes so high that it further suppressed the commercialization of innovation.

Eventually the market bounces back, right?

The Dow flirted with the 1,000 level throughout the decade, but did not cross the line definitively until 1982, an astonishingly long period to stagnate, nearly a generation.

You just had to wait from 1966 to 1982 to sell a stock for more than you’d paid… in nominal dollars. Shlaes fails to point out that you’d need $3 in June 1982 to have the same spending power as $1 in 1966. On an inflation-adjusted basis (chart), the DJIA didn’t exceed its 1966 high until 1996, i.e., 30 years later.

What about all the great stuff that happened in the 1960s? Going to war in Vietnam was a terrible decision, of course, but continuing Eisenhower’s work in desegregation wasn’t, surely. The author says “Well…”:

The early civil rights laws, as important as they were, set a precedent for federal supremacy over states to an extent some of the Constitution’s authors would have likened to tyranny. The later civil rights laws, with their emphasis on group rights, pitted Americans against one another. Both Johnson and Nixon conducted domestic policy as if they were domestic commanders in chief.

Already I can see some stuff that seems wrong or at least not supported.

For today, the contest between capitalism and socialism is on again. Markets do promise strong growth; we do live in a creative society, the most creative in the world, creative enough to lift the nation to new heights. Yet new, progressive proposals bearing a strong resemblance to those of Michael Harrington’s and his peers’, from redistribution via taxation to student debt relief to a universal guaranteed income, are sought yet again. Once again, many Americans rate socialism as the generous philosophy. But the results of our socialism were not generous. May this book serve as a cautionary tale of lovable people who, despite themselves, hurt those they loved. Nothing is new. It is just forgotten.

How does the author know that the U.S. is “the most creative in the world”? Why isn’t it equally plausible that our wealth was built on stealing a huge chunk of land from the Native Americans rather than on some sort of unique creativity? If it was the land that made us comparatively rich, combined with the wars and Communism consuming our competitors in the 20th century, then we aren’t guaranteed to get richer going forward. Taking the long view, it is the Chinese and Europeans who have

Full post, including comments