Catching up on 2017 must-reads for Bostonians, I recently enjoyed The Great Halifax Explosion: A World War I Story of Treachery, Tragedy, and Extraordinary Heroism by John U. Bacon.

The main story is familiar, but worth retelling.

All explosives require two components: a fuel and an “oxidizer,” usually oxygen. How destructive an explosive is depends largely on how quickly those two combine. With “low explosives,” like propane, gasoline, and gunpowder, it’s necessary to add oxygen to ignite them and keep them burning. If a fire runs out of oxygen, it dies. Another factor is speed. The rate of the chemical reaction, or decomposition, of low explosives is less than the speed of sound, or 767 miles per hour. In contrast, a “high explosive” combines the fuel and the oxidant in a single molecule, making each one a self-contained bomb, with everything it needs to create the explosion. To ignite, a high explosive usually requires only extreme heat or a solid bump. Once started, the dominoes fall very quickly, ripping through the explosive material faster than the speed of sound.

“She had a devil’s brew aboard,” Raddall states of the Mont-Blanc, a perfect combination of catalysts, fuel, and firepower. The ship’s manifest included 62 tons of gun cotton, 250 tons of TNT, and 2,366 tons of picric acid, the least understood of the chemicals on board, but the most dangerous.

After the shipwrights had so carefully built the magazines, hermetically sealing each compartment, and the stevedores had packed it all systematically, the French government agent operating out of Gravesend Bay received a last-minute order from his superiors in France to pack what little space remained on Mont Blanc with urgently needed benzol, an unusually volatile fuel, the latest “super gasoline.” The stevedores followed orders, swinging 494 barrels containing 246 tons of the highly combustible accelerant into a few unused spaces belowdecks, on the foredeck, and at the stern, where they stacked the fuel three and four barrels high and lashed it with canvas straps, a somewhat slapdash approach compared to the thoroughness with which the shipwrights had built the magazines. When the crew walked past the drums on deck, they could smell the unmistakable reek of the benzol. With the final addition of the benzol, Mont Blanc now carried an impressive array of the most dangerous chemicals known to man at that time. While benzol can’t match the pure power of gun cotton, TNT, or picric acid—all high explosives—what the stevedores probably didn’t know when they stacked the barrels of benzol on deck was that the airplane fuel needed only a spark to ignite, while picric acid doesn’t explode until it reaches 572 degrees Fahrenheit, and TNT does not detonate until it reaches 1,000 degrees. But by making the last-minute decision to store most of the fuel on the deck and the TNT and picric acid below, the crew had unwittingly constructed the perfect bomb, with the easy-to-light fuse on top, and the most explosive materials trapped in the hold below.

Canada had a much larger stake in the war than did the U.S.:

Halifax sent 6,000 sons to the Great War, roughly a quarter of its male population. It seemed almost every home had sent a brother, a husband, a father, or a son. The Great War drained the town of its able-bodied young men and left behind women, boys, girls, and men too old or infirm to fight.

One question worth pondering is why more people didn’t chicken out and escape to the U.S. They knew what the trenches were going to be like:

When fresh recruits got to Halifax, they frequently made a beeline for any place that sold alcohol, where they met soldiers who had been recently discharged, were on leave, or were about to head back to the trenches. They told the recruits stories so horrifying that they might have been tempted to think they were exaggerating. The experienced soldiers knew the average infantryman lasted only three months before getting wounded or killed, so they were determined to make the most of their time on the safe side of the Atlantic. Their hard-earned fatalism fostered a devil-may-care disposition and all the elements that came with it, including scores of prostitutes from across Canada and bootleggers so fearless that they set up shop in the downtown YMCA—which was probably not what the YMCA’s benefactor, Titanic victim George Wright, had had in mind when he wrote his will. During the war years, Halifax experienced a spike in venereal disease and out-of-wedlock births. Local orphanages had to expand.

The Mont-Blanc makes it from New York to Halifax without incident, but before the sailors can go to the YMCA for a drink, there is a low-speed collision with another ship. The author describes the impact that resulted in the explosion as entirely the fault of the Imo‘s captain and pilot (see Wikipedia for a quick summary, but I highly recommend this part of the book). More than 10,000 people were killed or wounded. The book covers this staggering tragedy, but this post is about the physical destruction and the estimated cost of rebuilding:

The explosion destroyed 1,630 buildings and damaged 12,000 more, leaving some 25,000, almost half the population of Halifax-Dartmouth, without adequate housing and dangerously exposed to the elements.

After the fires had been extinguished and the wounded tended to, Colonel Robert S. Low assembled an army of carpenters, masons, plumbers, and electricians to rebuild the city, which had incurred more than $35 million in damages in 1917 U.S. dollars, or $728 million today.

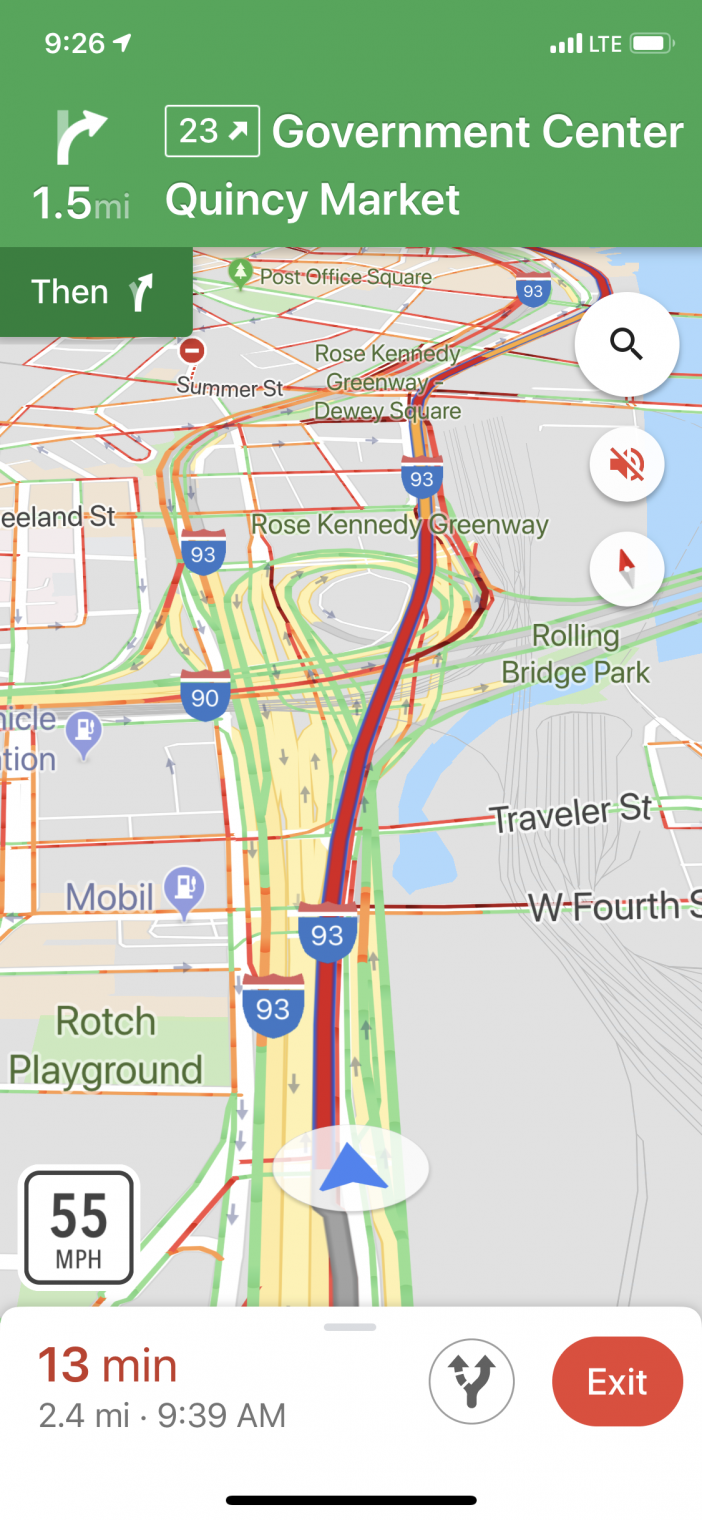

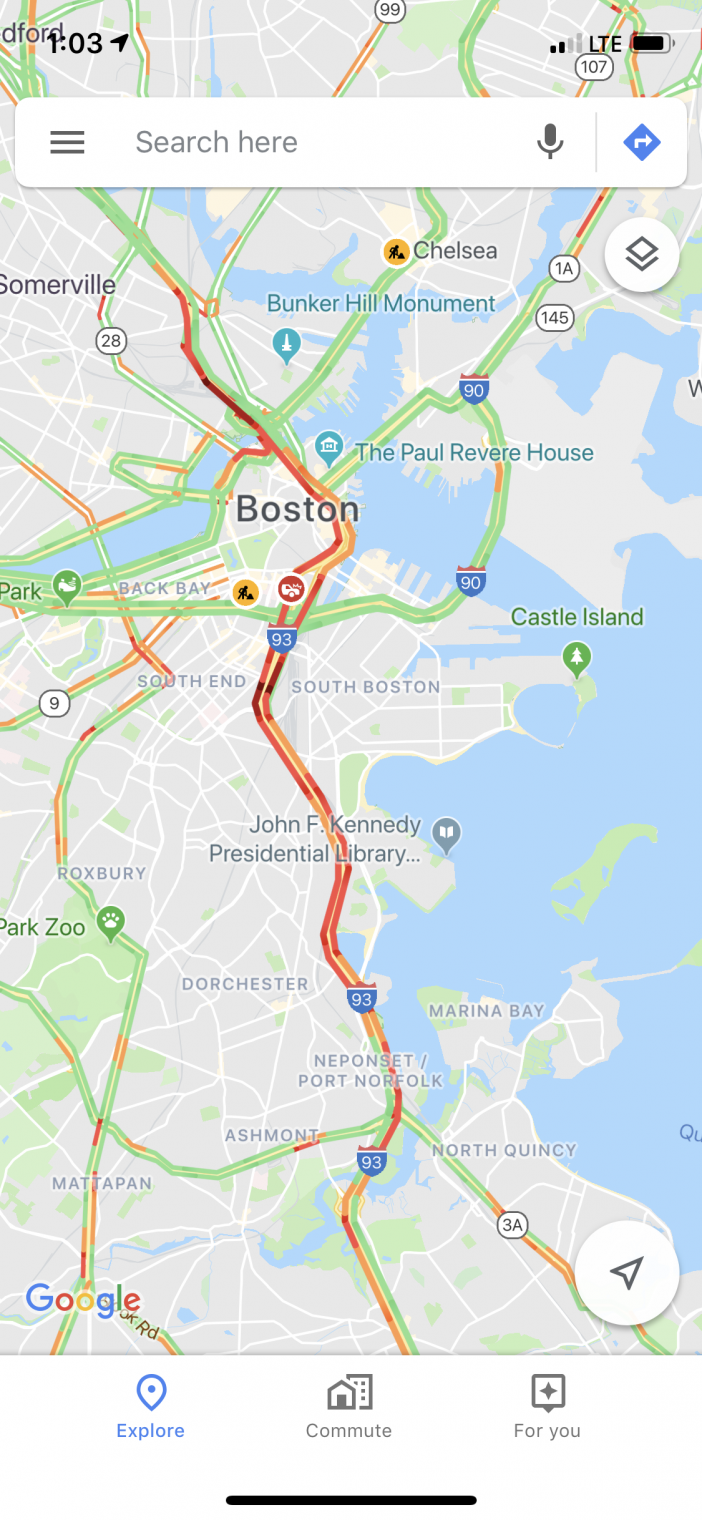

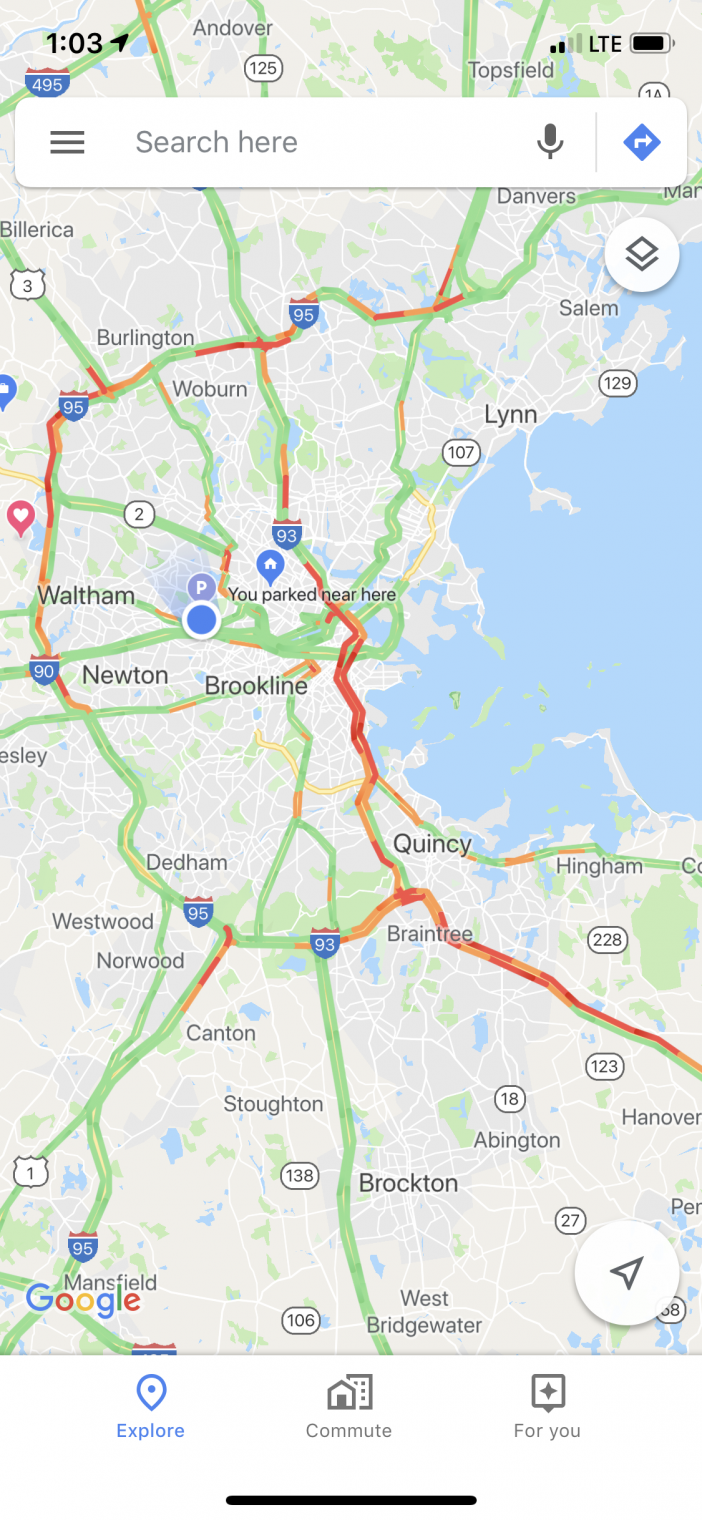

It cost only $728 million to rebuild a whole section of a city. Our town will soon spend $110 million to renovate/rebuild a school that can hold only about 600 students. I talked with a guy recently who is involved in a $1.5 billion project to create 2,700 “affordable” apartments here in the Charlestown section of Boston (story). That’s $555,555 per apartment (less than 1,000 square feet on average) on land provided for free (city already has a housing project on the same footprint). Presumably these will be higher quality than whatever was built in Halifax in 1918.

[Note: poor people who are selected by the housing ministry to move into one of these apartments would actually be rich almost anywhere else in the world if they could only get their hands on the $555,555 capital cost as a direct grant instead of as an in-kind service! If they could also get their hands on the monthly operating cost and combine that with interest on the $555,555 they would be able to enjoy, without working, a middle class or better lifestyle in many of the world’s beach destinations.

How about folks who work at the median wage? That’s about $23/hour in Massachusetts (BLS) or $46,000 per year. NerdWallet says that someone earning this much in MA can afford a $258,500 house if he or she has saved $60,000 for a down payment, has a top credit score, and spends $0/month on food and other non-housing expenses. Zillow says $274,416 on a nationwide basis. So a dual-income couple in which both partners earn the median wage wouldn’t be able to afford one of these units without a taxpayer subsidy, even if land were free and the unit were sold at zero-profit construction cost. The U.S. has apparently become a society in which Americans can’t afford to live like Americans!]

Maybe costs are lower up in Canada? Yes, but only a little:

Instead of drifting back into another long sleepwalk, Halifax has been accelerating, spending $11.5 million in 1955 to build its first bridge across the channel, another $31 million to build the second, right over the Narrows, and another $207 million in 2015 to raise the first bridge a few meters so container ships could get all the way to a dock in Bedford Basin. The city has spent $350 million to build a boardwalk along the bay and $57 million for a shiny new library downtown, an architectural centerpiece CNN judged to be the ninth most beautiful library in the world.

How about some other costs? A survivor of the explosion gets “$100 to enroll at the University of Michigan in 1919”. That’s $1,500 in today’s money, less than 1/30th of current tuition. He marries an American (same word “marriage” used, but really a different activity in those days before no-fault divorce):

Shortly after that invitation, Barss asked Helen to marry him. She said yes, but asked him to keep it between them until February, “so that if either of us wanted to get out of the deal, no one would be hurt.” Further, if Barss’s professors found out he was getting married, which med school students were forbidden to do, he could be expelled. “My father liked Joe & asked if he were a Republican or a Democrat,” Helen wrote. “He said he was a Canadian and voted for the man—Father said ‘If you ever live here and have anything or hope to have anything, you’ll be a Republican in self defense.’ ”

Maybe it is good that this guy died before Elizabeth Warren and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez proposed their latest tax plans!

I found the numbers in the book sobering. If we wear down the infrastructure that we have or if perhaps it is destroyed for some reason, it doesn’t seem as though we could afford to rebuild it.

More: Read The Great Halifax Explosion: A World War I Story of Treachery, Tragedy, and Extraordinary Heroism

Related:

Full post, including comments