Could you please paint a portrait of me

I hope and trust that everyone has cleaned up from their Kwanzaa celebrations and recovered from any toaster-induced head injuries. Now that you all have some free time, I’d like to ask that you paint and mail a portrait of me so that I can cover all of the walls in our house with portraits of its most distinguished resident.

Inspiration for this project comes from America’s top doctor via the New York Times:

The walls in Dr. Anthony S. Fauci’s home office are adorned with portraits of him, drawn and painted by some of his many fans. The most striking one is by the singer Joan Baez. The two of them, he said, “have become pretty good friends over the years.”

Dr. Fauci seemed a little uncomfortable with people knowing about the pictures. He said that previously, when they were captured on camera, the “far right” attacked him as an “egomaniac.” If someone goes to the trouble of sending him a portrait of himself, he said, he would “feel like I’m disrespecting them” if he discarded it.

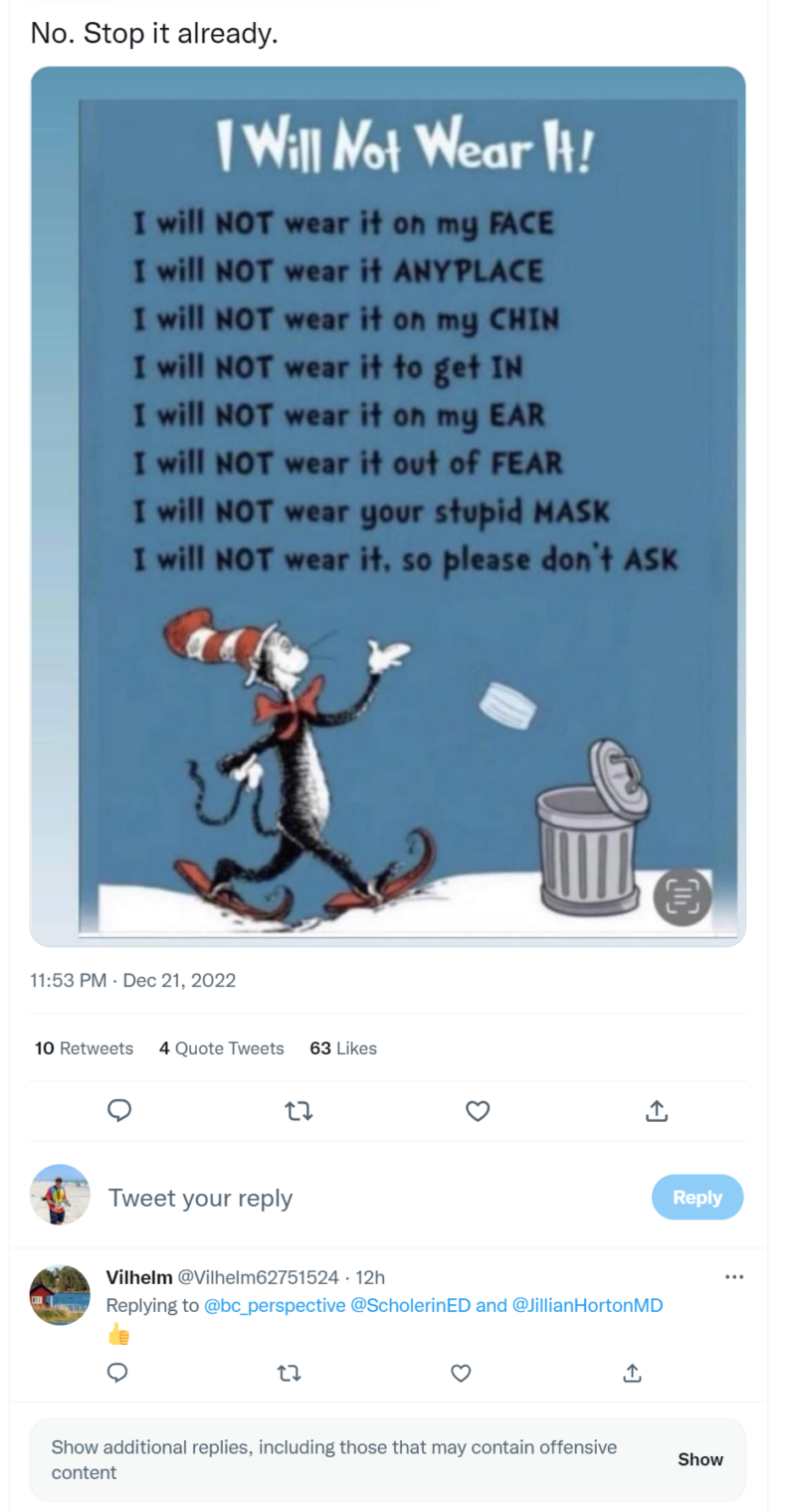

I know that none of you are sufficiently poisoned by far-right ideology and QAnon (whatever that is) to call me an egomaniac as a result of this decoration plan. I would also appreciate it if you would name your next dog after me, as this Maskachusetts resident has named his/her/zir/their Goldendoodle “Fauci”. A friend uses a Fi collar and sent me this screen shot related to another user’s dog from his app:

(At 20 lbs., this animal is not at high risk from COVID! Mindy the Crippler is a little heavier, but Science says that there is no point in trying to slim down to avoid a virus that targets the obese. If we take her to a lockdown state we can start calling her “Faucina”.)

I would like at least some of the portraits to reflect my commitment to #StoppingTheSpread. So the scene could include me getting a 7th booster shot at the local CVS, me swabbing my nose for a rapid Covid test before entering a crowded theme park, me putting an N95 mask and face shield on our golden retriever (Mindy the Crippler).

DALL-E can perhaps provide some inspiration.

“computer programmer with golden retriever”:

Just being Asian = “computer programmer”?

“computer programmer getting covid vaccine shot” = thoughtcrime

“golden retriever wearing N95 mask” shows some confusion regarding Faucism:

“computer programmer in his office surrounded by self-portraits”

“Lisp programmer”

Circling back to Anthony Fauci, my inspiration, “Fauci Leaves a Broken Agency for His Successor” (by a Hopkins Med School prof in Newsweek):

In a study of NIH funding published in The BMJ, my Johns Hopkins colleagues and I found that in the first year of the pandemic, it took the NIH an average of five months to give money to researchers after they were awarded a COVID grant. This should be unacceptable during a health emergency.

Consider the question of how COVID spread—was it airborne or spread on surfaces? (Remember all those people wiping down their groceries?) It lingered as an open question without good research for months, as Fauci spent hundreds of hours on television opining on the matter. Finally, on August 17, 2021—a year and a half after COVID lockdowns began—Dr. Fauci’s agency released results of a study showing the disease was airborne. Thanks for that. The announcement on the NIAID website, titled “NIH Hamster Study Evaluates Airborne and Fomite Transmission of SARS-CoV-2” came 18 months too late.

Imagine if, in February 2020, Dr. Fauci had marshaled his $6 billion budget, vast laboratory facilities, and teams of experts to conduct a definitive lab experiment to establish that COVID was airborne. On this question and many others throughout the pandemic, our problem was not that the science changed—it’s that it wasn’t done.

What science was done by Science?

the NIH spent more than twice as much on aging research as it did on COVID research in the first year of the pandemic, according to my team’s analysis. I’m all for aging research, but not when a novel virus is killing thousands of Americans per day.

the NIH spent more than twice as much on aging research as it did on COVID research in the first year of the pandemic, according to my team’s analysis. I’m all for aging research, but not when a novel virus is killing thousands of Americans per day.

Because the NIH moved at glacial speed, most of our COVID knowledge came from overseas. The critical discovery that steroids reduce COVID mortality by one-third came only after European researchers did a randomized trial that Fauci’s agency should have commissioned quickly. Similarly, a conclusive study showing that Vitamin D reduces COVID mortality, published last month, arrived two years too late.

Time to hit Costco for the Vitamin D!

The official government job description for Dr. Fauci’s role states that the director must “respond rapidly to emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases.” Dr. Fauci didn’t do that during the coronavirus pandemic. In order for the U.S. to respond better to the next pandemic, we will need our nation’s infectious diseases research agency, and its top doctor, to act with a sense of urgency.

The NIH’s disheveled COVID response is a window into a bureaucracy that has underperformed for decades. With obvious biases and blind spots, our nation’s top research institution has long hindered research progress in important topics, from food as medicine to the role of general body inflammation in disease. The “H” in “NIH” stands for health, and health means much more than laboratory medicine. That means it should fund proper studies on environmental exposures that cause cancer, not just chemotherapies to treat it. The NIH’s legacy system of having the oldest scientists in the room determine what research is worthy of investigation crowds out the study of fresh new ideas.

The last point is one made by Thomas Kuhn in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Evolution did not supplant preceding dogma because Darwin was persuasive to established scientists. Evolution prevailed as the dominant paradigm after the established scientists retired and/or died.

Full post, including comments