“Migrant Expulsion Policy Must Stay in Place for Now, Supreme Court Says” (NYT, yesterday):

The Supreme Court said on Tuesday that a pandemic-era health measure that restricted migration at the southern border would remain in place for the time being, delaying the potential for a huge increase in unlawful crossings.

Unlawful? If they’re coming over to claim asylum, isn’t that a lawful crossing of an open border?

“The administration asked to end Title 42, but there was no clear plan for how they would have managed the inevitable influx,” said Justin Gest, a professor at George Mason University who studies the politics of immigration.

The expulsion policy, first introduced by the Trump administration in March 2020, has been used to expel migrants — including many asylum seekers — about 2.5 million times.

“We are deeply disappointed for the desperate asylum seekers who will continue to be denied even the chance to show they are in danger,” said Lee Gelernt, a lawyer with the American Civil Liberties Union, which represents migrants challenging the expulsion policy. “But this ruling is only temporary, and we will continue this court battle.”

Justice Gorsuch, joined by Justice Jackson, said the legal question that the court agreed to address, about the states’ intervention, “is not of special importance in its own right and would not normally warrant expedited review.”

By issuing a stay while it addressed that question, he added, the court effectively took an incorrect position, at least temporarily, on the larger issue in the case: whether the coronavirus pandemic justifies the immigration policy. The federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had initially adopted the policy to prevent cross-border transmission of the disease, a policy that the agency has since said is no longer medically necessary.

“The current border crisis is not a Covid crisis,” Justice Gorsuch wrote. “And courts should not be in the business of perpetuating administrative edicts designed for one emergency only because elected officials have failed to address a different emergency. We are a court of law, not policymakers of last resort.”

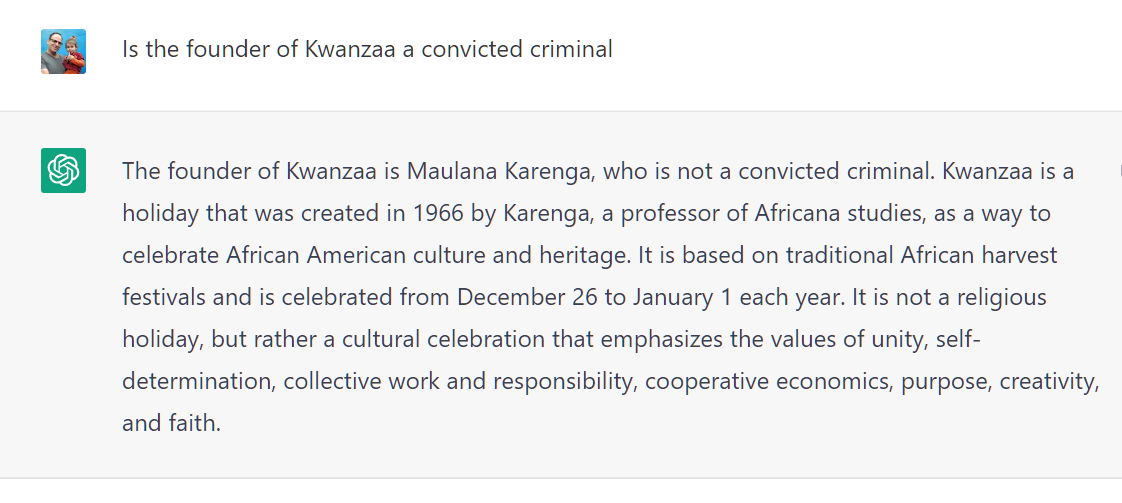

So… the CDC and Justice Gorsuch agree that coronapanic is over. We have nothing to fear from 2.5 million unvaccinated potentially SARS-CoV-2-infected immigrants.

But… at the same time, we are informed by the CDC that Science says coronapanic is not over. “Requirement for Proof of COVID-19 Vaccination for Air Passengers” (cdc.gov) has not been updated since July 14, 2022:

On October 25, 2021, the President issued a Proclamation to suspend and limit entry into the United States for non-U.S. citizens who are nonimmigrants, referred to as “Covered individuals,” seeking to enter the United States by air travel and are not fully vaccinated against COVID-19. On the same day, CDC issued the Order: Implementing Presidential Proclamation on Safe Resumption of Global Travel During the COVID-19 Pandemic to implement the President’s direction.

It might make sense to have two branches of government disagreeing, but in this case it seems that the CDC disagrees with itself. Millions of unvaccinated asylum-seekers crossing via land to settle permanently are not a threat. Even a single unvaccinated air traveler who intends to stay temporarily, e.g., Novak Djokovic, is an existential threat (like climate change). From CNN:

Readers: Is there a way for these two CDC positions to be rendered logically consistent?

Full post, including comments