Notes from a cross-country helicopter trip

To commemorate the heroic efforts of our government’s millions of armed police and soldiers in putting down the very-nearly-successful January 6, 2021 insurrection, let me relate my own recent trip to Washington, D.C.

I covered the first and last parts of this journey in Among the Covidians in Los Angeles and Washington, D.C.

Our journey began at the Robinson factory in Torrance, California (KTOA). Here are some photos that I took there in 2013 (they don’t allow pictures anymore).

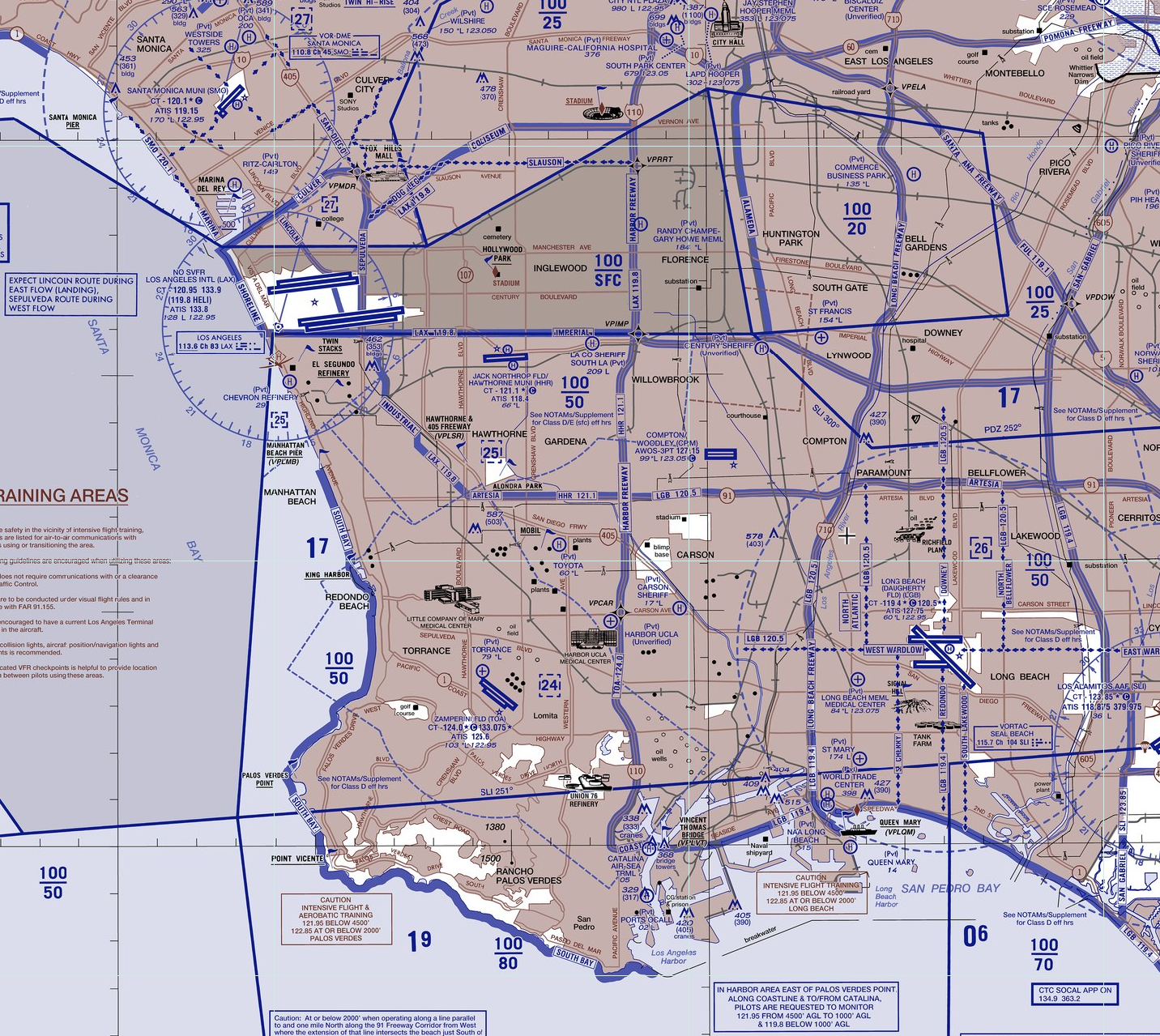

Getting out of Los Angeles we studied the FAA helicopter chart… (note that the official routes require some understanding of local highways)

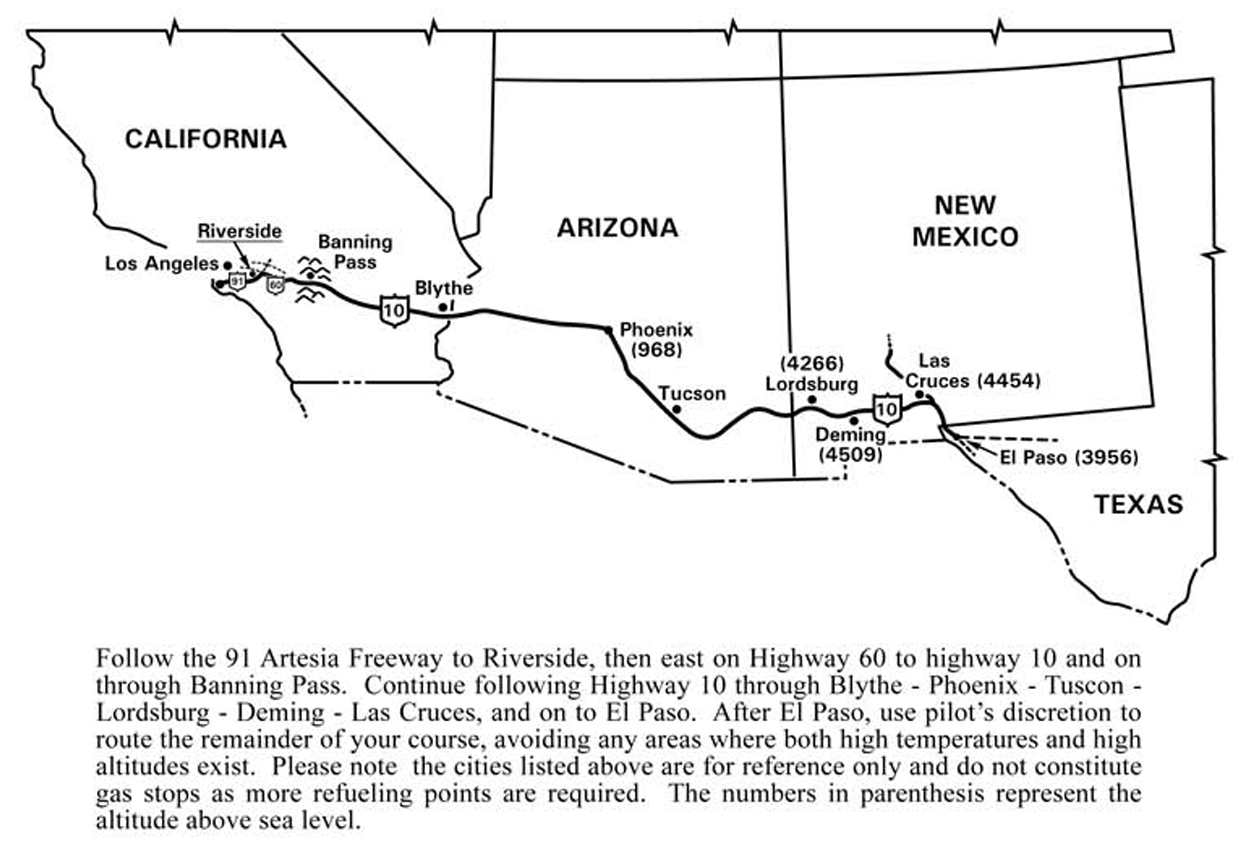

And the Robinson-specified route:

One thing that Robinson does not give to pilots fleeing the City of Lockdown is a list of frequencies and elevations for all of the airport traversed, so I prepped a couple of days before by writing all of these down on a pad (we were a bit too low to get advisories from SoCal Approach and therefore went from tower to tower). I handled the radio while my co-pilot (a former student at MIT 15 years ago and, having started a successful business, now proud owner of a $700,000 new helicopter) flew the machine. We made it out of LA without losing our certificates.

We passed the Morongo Casino and the Banning Pass into Palm Springs and a stop at KUDD:

After a stop at the Phoenix-Goodyear Airport, we made it to Tucson, Arizona just after dark:

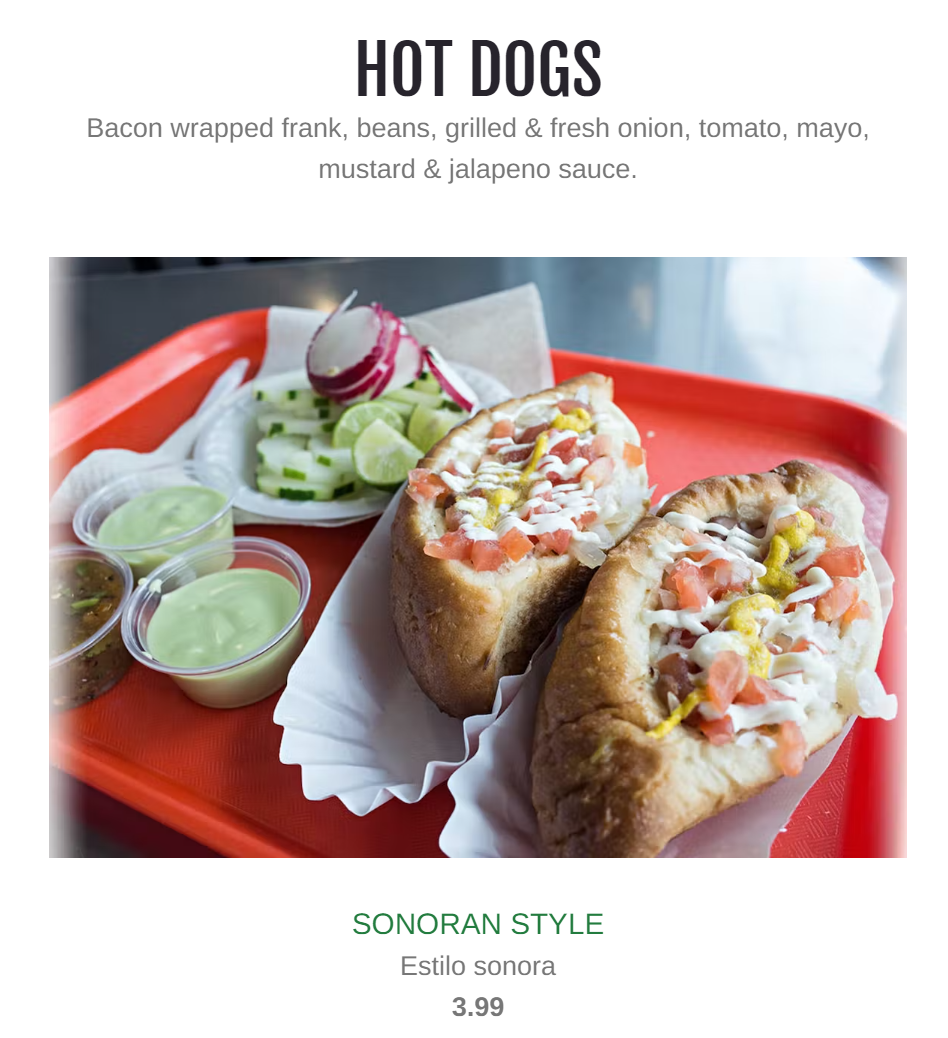

My co-pilot was skeptical as I waxed expansively regarding the marvels of the Sonoran hot dog at El Guero Canelo (James Beard award winner and also a song from Calexico). If you’re looking for shelter from Bidenflation, the $3.99 dish is ideal:

(Note that each hot dog costs taxpayers closer to $10,000 when military pilots stop in. Tucson/El Guero Canelo is, according to the FBO, a popular stopover on training excursions.)

The War on Christmas cannot touch the fortified positions of El Guero Canelo:

We cranked before sunrise at KTUS and headed into the mountains of New Mexico:

In El Paso we saw the cruel conditions suffered by asylum-seekers and reflected on Governor Abbott’s noble provision of bus transportation for those migrants who want to escape to sanctuary cities where progressives will cater to all of their needs.

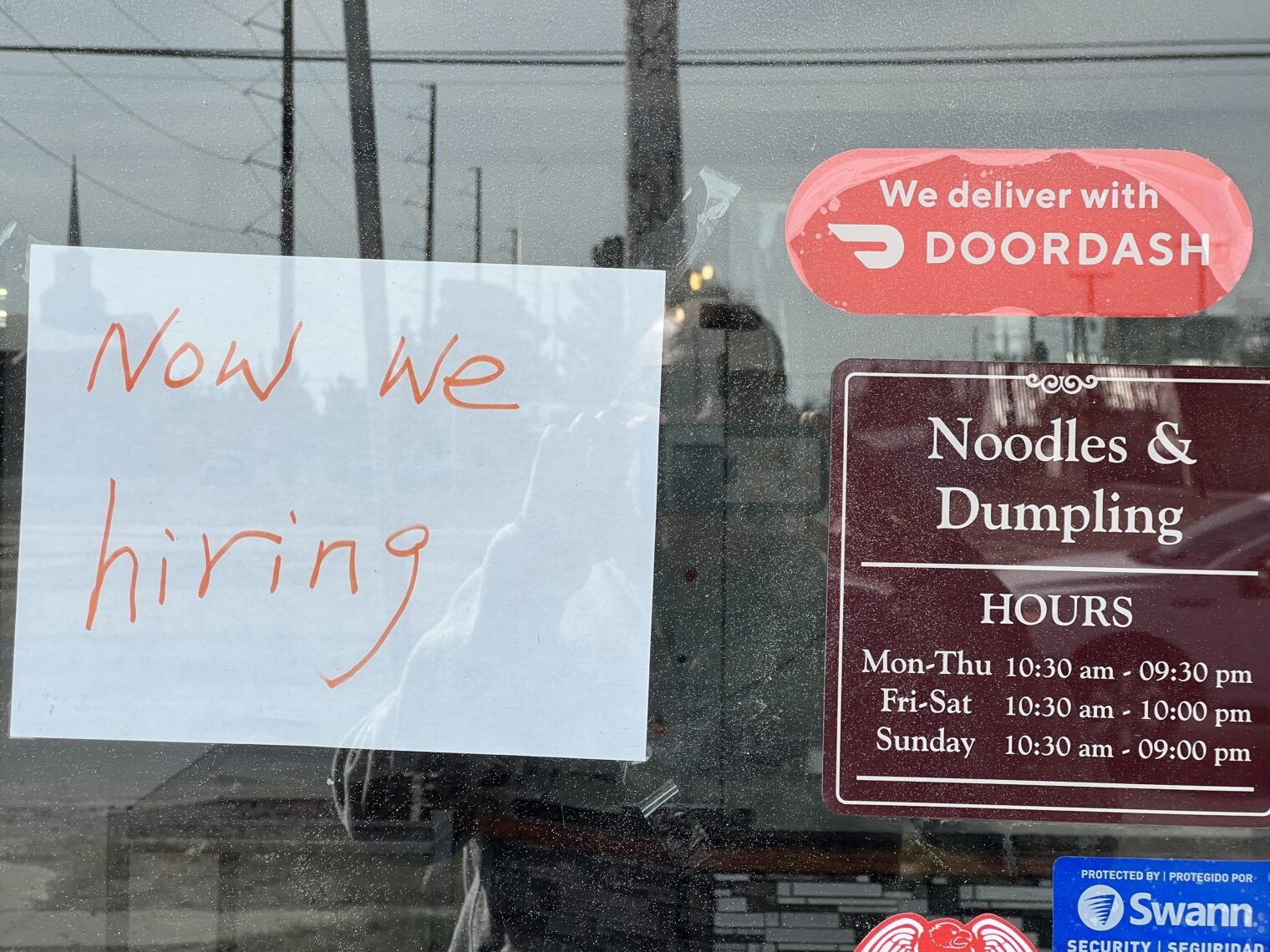

A 17-knot headwind, which was to be our near-constant companion, plagued us as we departed El Paso. In Pecos, Texas, we found the best dim sum west of the Pecos:

The help wanted sign was typical. Seemingly every retailer and restaurant was hiring in every town that we visited. A Texas FBO manager who had paid $13/hour in 2019 for entry-level jobs now has to pay $20/hour. “I still can’t find anyone who wants to work,” he said. (We also learned that the wholesale price for 100LL at the time was about $4.70/gallon.)

We continued to follow Interstate 20 over Midland, Texas and into Sweetwater.

It was freezing overnight and we hadn’t been able to find a heated hangar so we visited the National WASP WWII Museum to give the engine a chance to warm up before starting. We stopped for an awesome dim sum lunch at Bushi Bushi in Addison, Texas, also home to the most luxurious FBO that we visited during the trip: Galaxy.

We flew in the dark to Atlantic in Jackson, Mississippi and shut down for the night. We shared a heated hangar with an Ercoupe. Corporate says it is all about diversity and inclusion, but the employees had selected Fox News and were enforcing gender binarism:

Speaking of Fox, here’s a throwback to November 20 from the trip. Twitter was “in chaos” and presumably the site was at risk of shutting down due to all of the valuable employees departing:

The most emotional moment of trip for me was circling the Talladega Superspeedway, which happens to be right next to the airport. Ricky Bobby‘s NetJets was waiting:

All over the Southeast, the landscape was scarred by the Federal Reserve Bank’s 0% interest rates. I wonder how many of these developments won’t be finished any time soon. (A few weeks later, I was in Death Valley, California and talked to a Mountain States builder. He’d stopped doing any projects at all. “It costs $400 to $500 per square foot to build and I’m not sure that people will pay enough for me to recoup my costs.”)

Best airport restaurant of the trip (Elevation at KRYY near Atlanta):

Americans who have stolen $billions may relax in suburban comfort on the Stanford University campus and receive visits from attractive young females. For those of us who have stolen $thousands, we flew over quite a few housing options. Here’s an example:

A visit to Chick fil-A in Roanoke, Virginia:

A fly-by of Dulles Airport on the way to landing at KGAI.

There was minimal traffic in Montgomery County, Maryland as I traveled to my mom’s retirement complex on the Beltway. “The economy hasn’t come back,” said the Uber driver. “People in D.C. are still working from home or not working.” Did that mean his income had fallen? “No. There are fewer customers, but nobody wants to work either so the balance isn’t that different. Also, a lot of my customers are guys who lost jobs in 2020 and can’t afford child support payments that were ordered when they were working. They can’t renew their driver’s licenses because they’re behind on child support, so they take Uber to get to work.” (see this article on the scale of child support profits obtainable in Maryland)

The labor shortage made it tough to get a post-trip haircut. The barber shops were jammed with people who’d made appointments in advance. On the other hand, maybe Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act is working. One-way tickets from DCA to PBI were less than $200 just two days before Thanksgiving.

We were lucky with the weather, except for the headwinds most of the way and then some moderate turbulence from 30-knot winds around the Appalachian mountains toward the end of the trip that required us to slow down to 80 knots (best cruise in the R44 II is about 110 knots). Even though some of the infrastructure is frayed because so many Americans have withdrawn from the labor force, the U.S. private aviation infrastructure remains a marvel to behold. The bigger airports usually have FBOs that are staffed 24/7. There is usually a crew car when you need it. Air Traffic Control is always relaxed and helpful. Most of the fees to keep this going are rolled into the price of fuel (or, even better, paid for by the Gulfstream crowd) so you’re not hit with annoying small bites constantly as in Canada and Europe.

Full post, including comments