Christmas/Hanukkah/Kwanzaa thought: How Donald Trump can bring our divided nation together

2024 will be remembered, I think, as one of the best years ever for progressive Jewish American Democrats. Last month’s election could have been improved, of course, but the pain of that loss is more than made up for the fact that Hanukkah and Kwanzaa are almost perfectly aligned this year. The first full day of Hanukkah is December 26, which is also when the Harris family traditionally lit the first candle of the kinara during the 1960s when it became one of the first adopters of Maulana Karenga‘s new holiday (like Donald Trump, Professor Dr. Karenga, Ph.D. beat more women than Doug Emhoff. Because of prejudice against the Black man, however, Karenga was imprisoned for kidnapping and torturing women rather than being elevated to the Presidency).

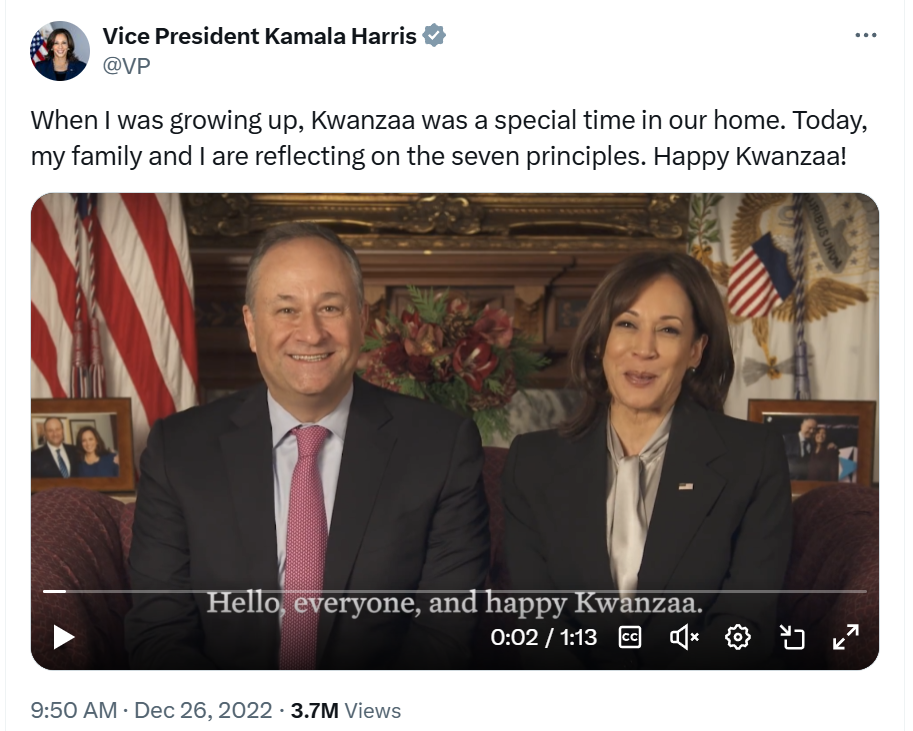

How about a Christmas wish that Donald Trump will begin the healing process for our divided nation by bringing Kamala Harris into his administration as Kwanzaa Czar? Other than Maulana Ndabezitha Karenga (born Ronald McKinley Everett), there doesn’t seem to be anyone better qualified.

What about a job for Doug Emhoff? Claiming to be a victim of domestic violence is one way for a migrant to obtain asylum here in the U.S. (see “Biden administration reverses Trump-era asylum policies” (Politico, 2021)). Mx. Emhoff could be an asylum court administrative judge evaluating tales of who slapped whom in the privacy of a home 8,000 miles away.

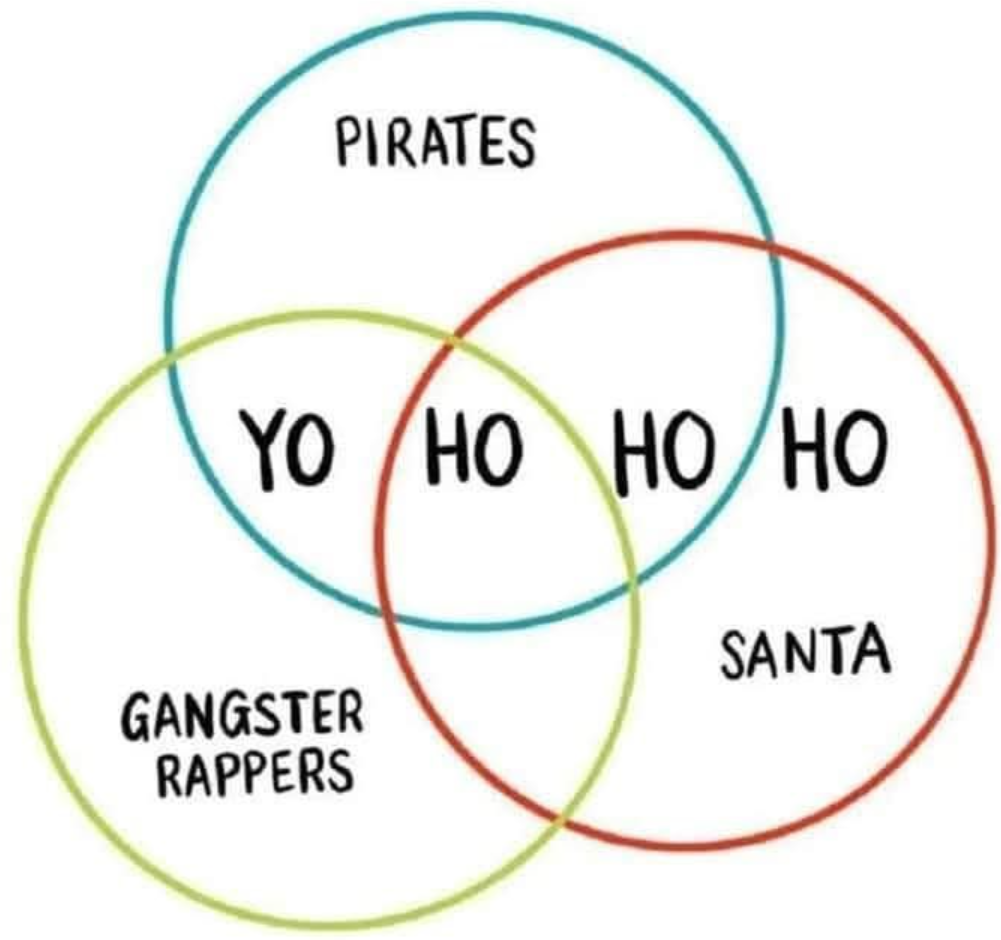

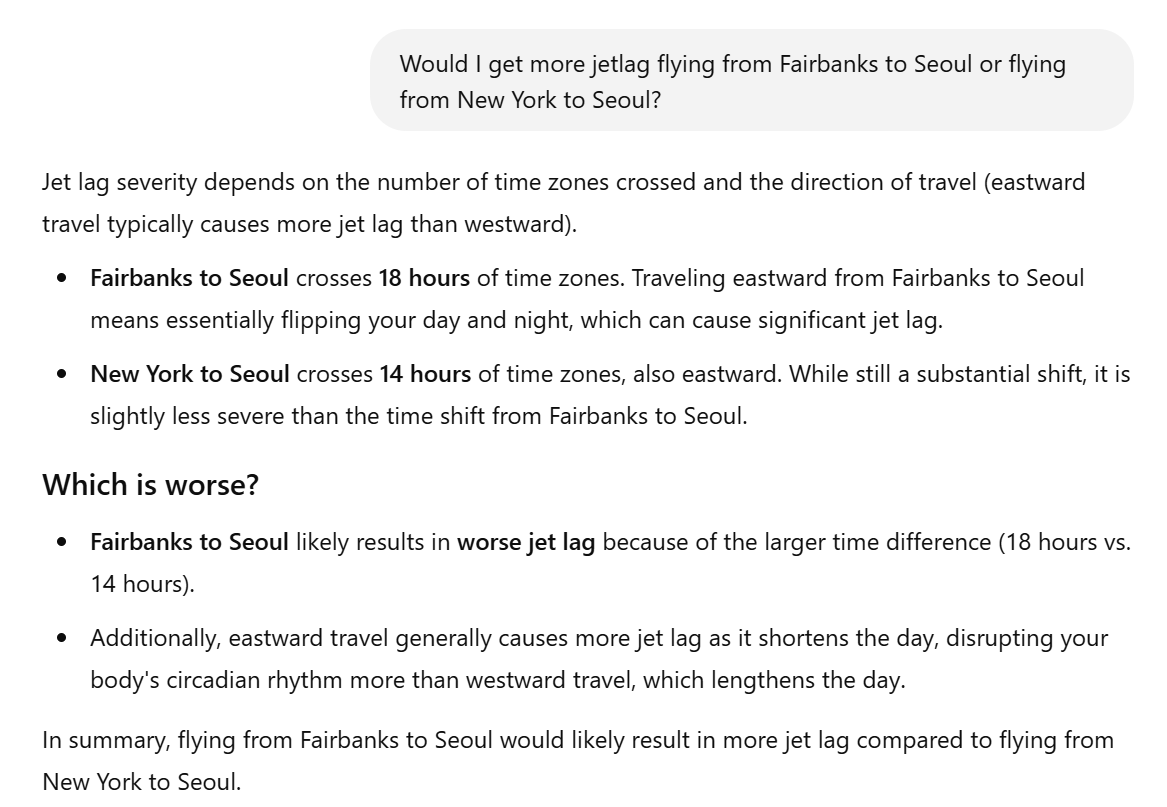

Finally, let’s remember how much seemingly different groups of people actually have in common. The following diagram should be helpful and inspiring:

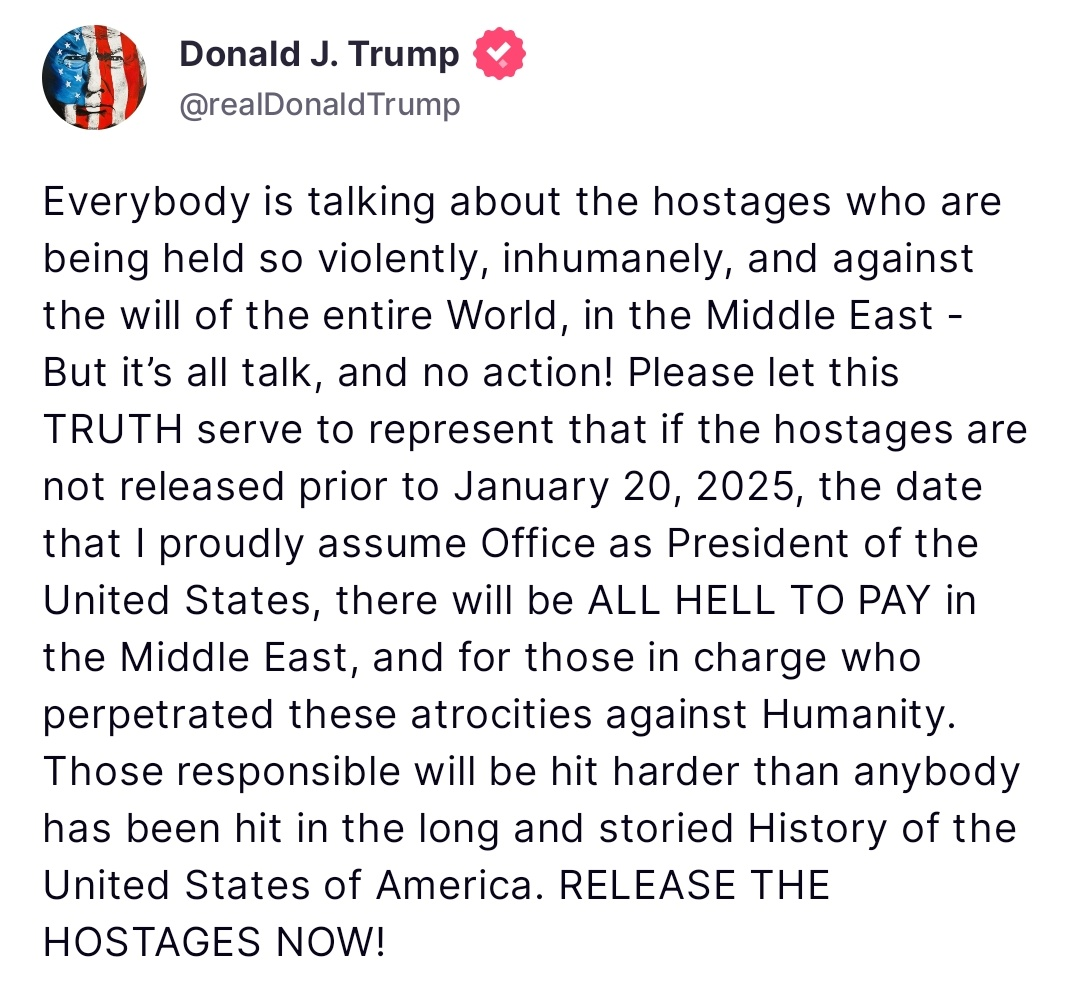

In case the above tweet is memory-holed:

Full post, including comments