Medical School 2020, Year 3, Week 2

“The first week was pure adrenaline. I never felt tired. This week I’m crashing hard,” comments Surgeon Sara, a classmate on the emergency surgery service, as we head up in our scrubs to the PCU at 4:45 am. I’ve learned that I need more time so I wake up 15 minutes earlier at 3:45 am. We both reminisce how we should have studied basic postoperative recovery timeline (e.g., Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol, pain medication regimens, anxiety meds, etc.).

Several of the attendings are on vacation so we have a light caseload for elective (non-orthopedic) surgery with the exception of the surgical oncologist’s cases. The Chief is very excited about “her Whipple” on Thursday. I let my classmate Charlie scrub in on some more melanoma cases while I try to get in on some cases on other services. There are always ample orthopedic cases going on all hours of the day (including Saturdays), so my goal is to find a joint replacement.

The first step is to check Epic for the “Status Board” of scheduled surgeries. There are no private desks or offices. Using a personal device is challenging due to VPN requirements for accessing the hospital’s Epic system. I take a rolling cart containing a Windows PC, which will connect via WiFi and Citrix, to the end of a deserted hallway. I find a shoulder replacement that looks interesting and watch a couple of videos in prep while consuming Cheez-Its and granola bars at 10:00 am.

Second step is locating the attending to ask if I can scrub in. Epic shows his name, but not a photo. His university profile page contains a photo, but these images are usually 10-20 years old. There are six attendings in the OR lounge, identified by badges, and I find him on my third attempt. “Of course, I’ll see you there in ten minutes.”

We’re doing a total shoulder replacement. I help retract as the surgeon hammers in the prosthetic joint parts. When finished, the surgeon steps out to begin another scheduled case and the PA allows me to close the incision sites under her guidance. I ask where I can get trauma shears, the most coveted item for medical students hoping to be useful during rounds and trauma alerts. They can be used for cutting clothes off a trauma patient, during dressing changes, and for chest tube removal.”Stay here” She disappears for 30 seconds and returns with a brand new pair.

I get out of this case and a follow-on shoulder arthroscopy (minimally invasive procedure using endoscopy to evaluate and clean out a joint) at 12:30 pm and find my team in the OR lounge. The cases are finished, and they are planning to check in with the intern before the Chief heads out for the day. I check the status board and notice an organ procurement procedure is posted. I ask my Chief if I can see that. “Yeah, they might already be finished.” As we are in the elevator, Christian Charlie mentions, “That’s awesome you’ll be watching an organ harvest. Good luck!” The Chief responds: “We don’t use the term harvest; it’s ‘organ procurement’. But yeah, they are surprisingly quick, in and out in 30 minutes, but you can’t beat the anatomy experience.” I head down to OR 10.

When I arrive, there are 10 people sitting on the floor outside the OR. The donor is 35 years old, suffered a car crash a week earlier, was declared brain-dead yesterday and had care withdrawn, thus initiating the donation cycle. Three different transplant programs have arrived — a heart, a lung, and a liver/kidney team. They’re waiting for final approval from the hospital’s legal department while the donor is kept perfused by the anesthesiologist, the one remaining member of our hospital’s team. The patient checked the organ donor box for his driver’s license years earlier, but the organ donor program (typically a contracted company for the state) also sought and received written consent from his wife, which initiated the transplant program (the care team never brings up the possibility of organ donation with a family). Two hours, the wife withdrew her consent and requested a delay for reasons that are unknown to us.

The heart team includes an attending, a cardiothoracic surgery fellow, and resident. I take them to the cardiology reading room so they can review the TEE (transesophageal echocardiogram) images to confirm an acceptable heart. Everyone agrees it is a strong heart. When we return, there is no resolution on the consent issue. I check back in with my team still in the OR lounge. Christian Charlie went home around 2:00 pm, and the Chief is packing up. I head back to the OR and take a seat with the transplant teams.

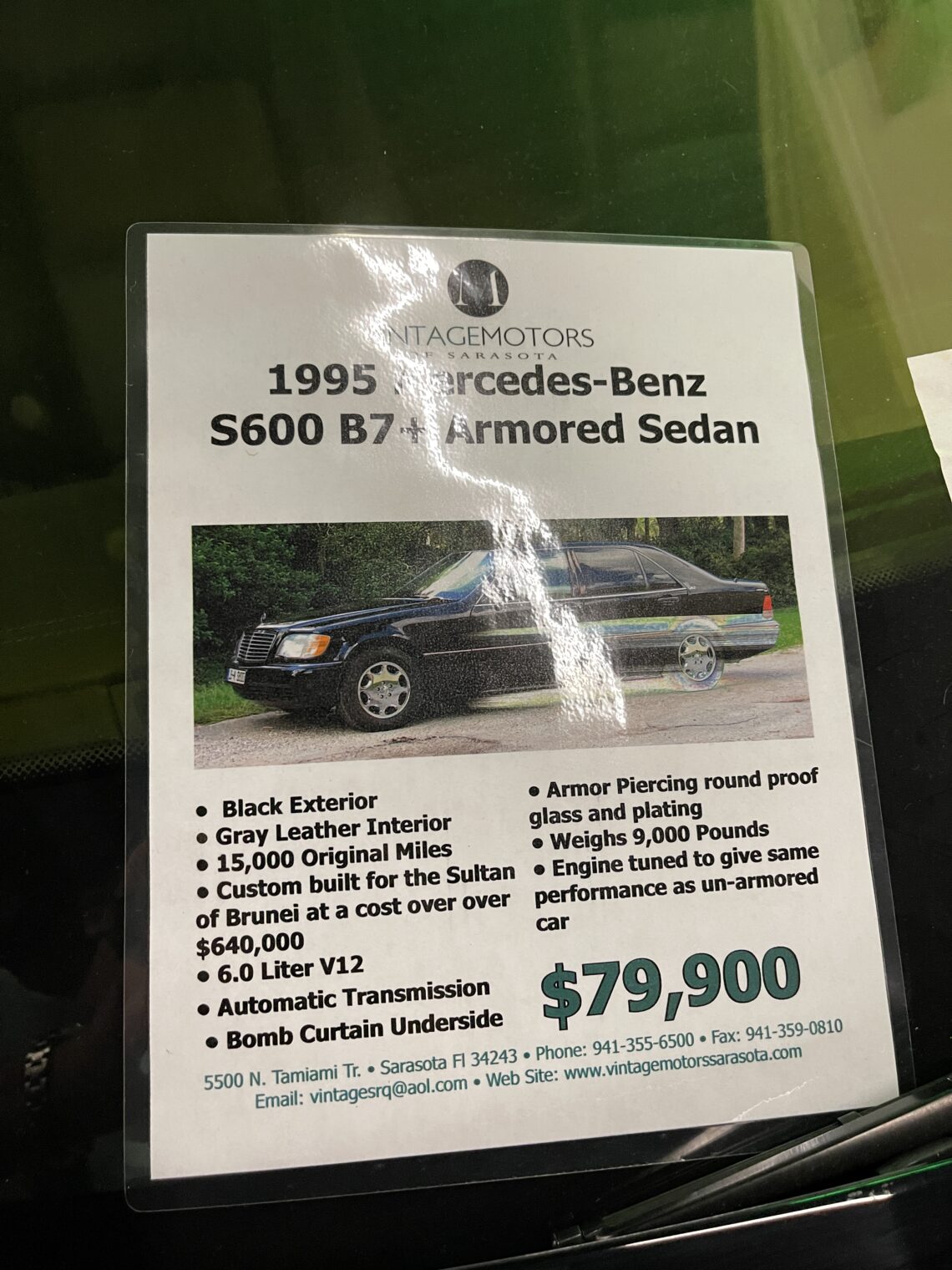

The surg tech explains that he is on call for blocks up to 72 hours, and has to be at his local airport within one hour of a call to board a business jet.

[Editor: Our Boston-area organ program has a Cessna CJ4 and the pilots work week-on/week-off shifts.]

The state-authorized transplant coordinator finally gets an update. The wife wants to cancel the donation. This ignites a tense discussion among teams and four institutions legal teams (our hospital’s, plus lawyers from each of the three hospitals that have sent transplant teams). The attending from the lung team wants to go ahead; the other two are leaning towards declining. A life-or-death situation calls for people to drawn on all of their philosophy, moral background, and legal training: “I’ll decline, if you’ll decline,” says the liver/kidney attending to the heart surgeon.

The lung team calls home to see if they can use the other organs, but the transplant coordinator begins calling further down the list. “We have to continue going down the list as long as my program and legal say its a go.”

“My responsibility is to my patients and their families back home,” says the lung surgeon in an Old World accent and a tone that would earn him a role in the next sequel to Silence of the Lambs. The heart attending: “If the wife starts talking to the press, this will set back transplant medicine a decade. I know we might have legal ground, but as a doctor if you are not comfortable with something you always have the right to decline.” The perfusionist on the lung team: “This doesn’t seem right.”

I leave at 7:00 pm and learn the next day that the organ procurement occurred at 3:00 am. Hannibal Lecter got his lung and two new teams jetted in overnight for the two two. Ultimately the widow had agreed to the procurement.

Thursday is the big day. The Whipple, a 6-11-hour procedure to remove a bile duct tumor (see Week 1). We are the first and only case scheduled for our OR. Only one student can be officially scrubbed in at once, so Christian Charlie and I agree to alternating two-hour shifts. We finish rounding at 6:45 am and head down to Pre-op to introduce ourselves to the patient. We help move the patient from her stretcher onto the OR bed, and the CRNA (Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetist) lets me intubate the patient!

Charlie scrubs in first. I’m not officially scrubbed in, but watch from a stack of three step stools behind the drapes at the head of the bed.

The chief begins with a large midline incision from one inch below the xiphoid to one inch above the pubis. Christian Charlie helps suction and retract. Once the parietal peritoneum is opened, the Chief uses clips and the Bovie to dissect the lesser omentum of the stomach. The attending questions Charlie: “What vessels are we cutting?” (short gastrics) and “What space are going into when we cut this omentum?” (lesser sac). Charlie won’t admit ignorance: “It’s something in the abdomen.” From my perch I ask, “Why don’t we have to remove the fundus if we take the short gastrics [that are supplying the fundus with blood]?” The attending explains, “The stomach is one of the most collateralized organs in the body. You can take a few vessel groups and it will still be happy.”

After about 30 minutes, they’ve gone too deep for me to see anything so I head off to my secret alcove and find the computer still there on its rolling cart. I watch YouTube videos of the Whipple procedure and read UpToDate as I eat Cheez-Its.

Charlie and I swap for the rest of the day. The most exciting part was when we were dissecting the common bile duct off from the portal vein. The tumor had spread into the adventitia of the portal vein requiring extreme care. “Careful, careful!” exclaimed the attending as he takes control from the Chief. The team will work until 11:30 pm, but Charlie and I have to leave for a required “learning environment” session at the medical school hosted by the Chief Diversity Officer. Charlie is unhappy about missing the rest of the operation and as we walk over, we encounter Ambitious Al, who had to scrub out of an exciting rib plating on a car accident victim (“MVC” for “motor vehicle crash”). “They might have let me do the chest tube.”

We are 10 minutes late, but people are still filing in. We watch the same PowerPoint that we’ve seen four times previously in two years about types of reportable mistreatment. The Chief Diversity Office maintained an excited high-energy tone through slides defining harassment and avenues for reporting it, but many students took advantage of this break to check Facebook and Amazon from their laptops. Those on surgery rotations whispered about what they were missing. Last year’s 45-minute lecture has been extended to 2 hours and 15 minutes total, including a 1.5-hour block for 8 students to go through scenarios with a dean.

We get a one-paragraph description of a case and each student is required to say something before we move on to the next one. A sample of the 11 cases…

Case 1: A surgeon hits a student’s hand that is holding an instrument and yells, “Don’t do that.” The student begins to cry. Our Chief Diversity Officer opens: “The attending should never hit a student. Period.” Lanky Luke: “We don’t know the full story. Maybe the student was about to do something really bad on the patient, and it was a light tap, saying don’t do that.” Canadian Camy: “That is still inappropriate. It makes you feel very uncomfortable, especially if it is a male hitting a female.”

Case 2: The chair of the department notices a female medical student studying in the library. The chair begins asking questions about the subject, which she can’t answer. He continues to press, until she begins to cry. Class President: “There is a clear distinction between teaching versus emotional distress. There is no reason to push someone until embarrassment and mental distress.” Type-A Anita: “Sounds like a douchebag old white male getting off on a powertrip.” Chief Diversity Officer: “I love that! I’ll have to use that with next year’s group.”

Case 3: Two males and two females are on an away rotation. The two males become good friends with the residents while playing basketball after work. They start to go on “boys night out”. The two female feel like they are getting less OR time and less teaching time. Is this inappropriate? Type-A Anita: “Everyone should be given the same opportunities.” Chief Diversity Officer: “I think there is a win-win scenario here. The women should ask to meet up with the team for drinks after basketball so everyone gets to know each other.” [Editor: What if the two females are Muslim and don’t drink?]

We get out at 7:30 pm and start at 4:30 am Friday morning for more of the same.

Christian Charlie and I begin a 24-hour call shift at 6:00 am on Saturday. We join the Chief, Quiet Quincy (PGY 3), and Prego Patricia (an intern

Full post, including comments