How did Hurricane Fiona, a Category 1 storm, knock out Puerto Rico’s power?

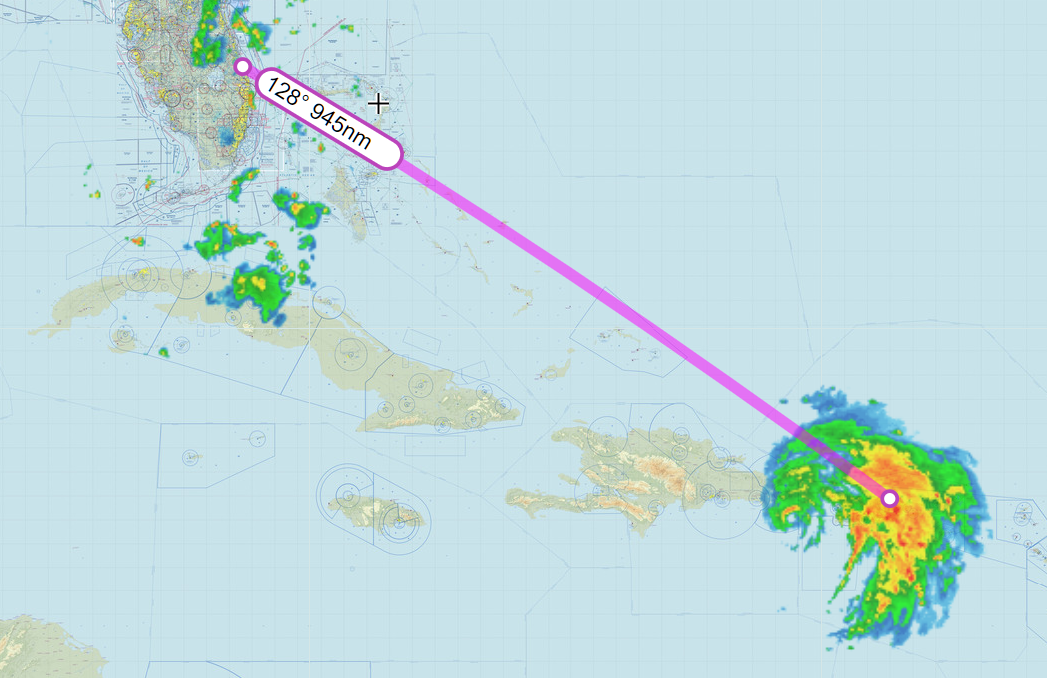

A few media-following friends in the Northeast have been checking in, concerned that Hurricane Fiona, which knocked out power in Puerto Rico, is also trashing our neighborhood. They are reassured to learn that Puerto Rico is 1,000 miles from Palm Beach County, but it has made me wonder… given that (1) Fiona is only a Category 1 storm, (2) Puerto Rico can expect something similar every year or two (history), and (3) the power grid in Puerto Rico was recently rebuilt to the latest standards (after the 2017 Category 5 Hurricane Irma), why were the reported 85 mph winds enough to take the system out?

Is it simply impossible to make above-ground lines robust enough to handle 85 mph winds? Is the problem that trees will inevitably come down and break the lines even if the lines wouldn’t have been blown down? (But a newly engineered grid should be able to handle quite a few individual tree impacts because the power would be routed around the cut line.)

From state-sponsored NPR in 2021:

It’s been four years since Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico’s electric power grid. Yet even after billions of dollars were allocated by the federal government to repair it, the island’s energy infrastructure is still in terrible shape. Blackouts continued this summer as the two entities responsible for operating the grid pointed fingers at each other over who is to blame. One of those two entities is Luma, a private company that was awarded a contract last year to distribute electricity around the island. The other is the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority, known as PREPA, which used to be in charge of the whole system and now continues to operate the power plants.

The restoration process is very bureaucratic because you have Luma going through FEMA’s process, going through the Puerto Rico Energy Bureau’s process. And you also have Luma going through federal process and going through Puerto Rican process. And you know what? There’s not a single work already done with reconstruction funds. They’re still planning and designing. So this will take a lot of years before we see something better.

An IEEE article from 2018 doesn’t explain any of the engineering or technical details:

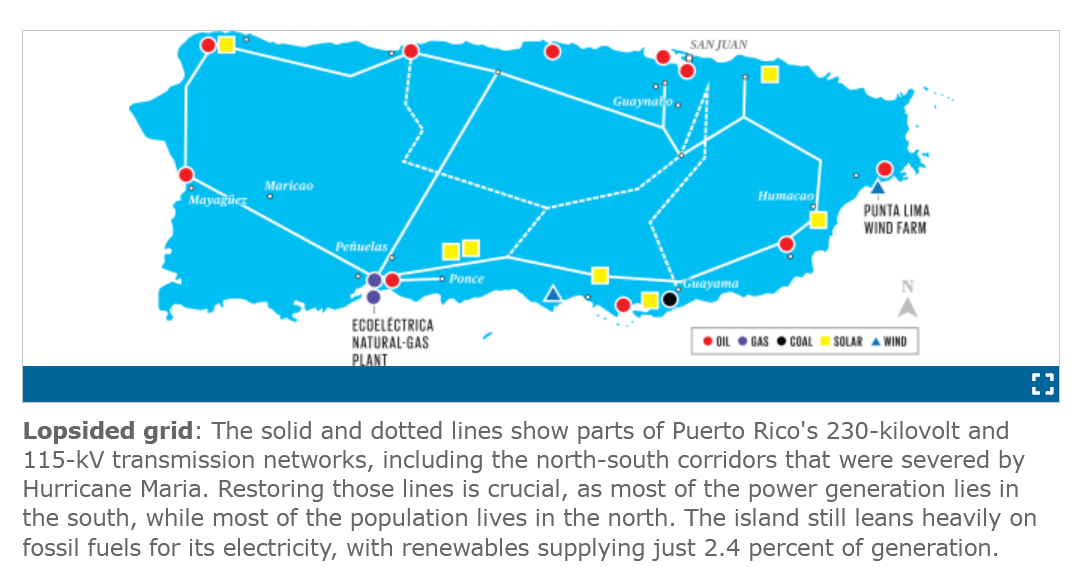

This past December, I traveled to Puerto Rico to report on this massive undertaking. I found contradictions everywhere I went. I saw utility workers fanned out across the island, yet progress remained excruciatingly slow. I met rank-and-file PREPA employees working flat out to restore power, yet each day brought a new report of fumbles at the utility’s top levels. And I heard many smart and exciting ideas for how to build a modern, resilient grid in Puerto Rico, even as the urgent need to restore power meant resurrecting the vulnerable existing system.

KSUA to TJSJ (skyvector):

Are we going to see “I stand with Puerto Rico” Facebook profile images? Or will people stick with this one:

Full post, including comments