Book review: Ferry Pilot

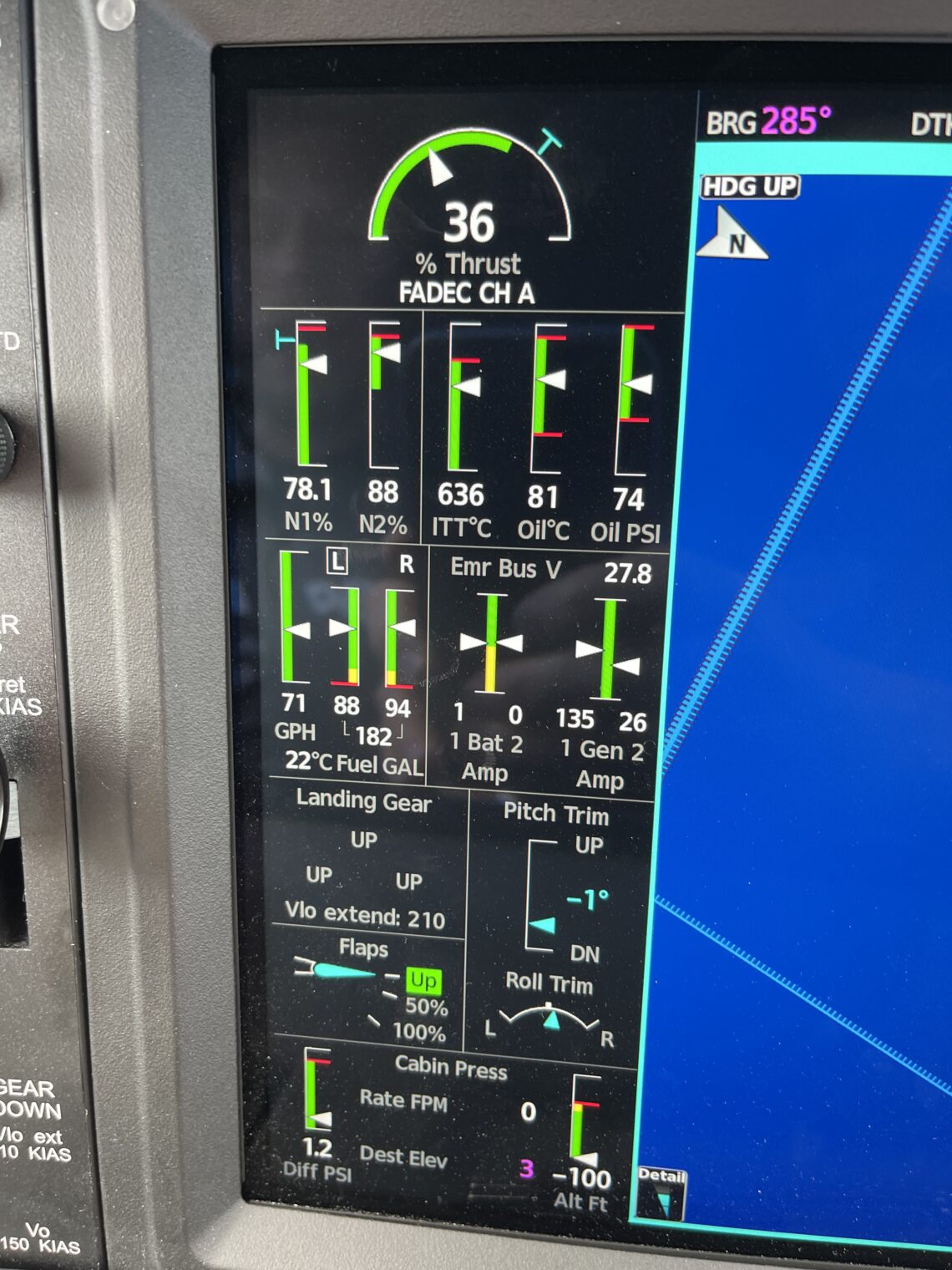

FERRY PILOT: Nine Lives Over the North Atlantic, by Kerry McCauley, is about taking transoceanic trips in planes that were engineered for $50 hamburger missions (now $500 thanks to the inflation that the government tells us does not exist…). These planes might have only one piston engine, one alternator, one battery, one attitude indicator, etc. In other words, many single points of failure and each point reasonably likely to fail during a 10-hour leg.

The book opens by quoting Marco Polo: “An adventure is misery and discomfort, relived in the safety of reminiscence.”

Icing is a persistent enemy:

The turbulence started almost immediately. I tightened my seat belt and concentrated on the instruments in a futile attempt to keep the plane on its assigned heading and altitude. Shortly after entering the clouds, a frosty haze of ice started building up on the windshield. I looked out the side window and I saw that a layer of rime ice was building up on the leading edge of the wings and the landing gear. Picking up ice really got my attention because encountering icing conditions in a small plane like the Cessna 182 is considered an emergency situation because the anti-ice systems are almost nonexistent. They consisted of a heated pitot tube to keep the flight instruments functioning and a windshield defroster that will do next to nothing in heavy ice. I wondered if I could open the side window and scrape at it with my fingernails if the ice got too thick. As ice accumulates on the leading edge of the wings, the airflow gets disturbed, reducing their ability to produce lift. Add to that the increased weight of the ice itself accumulating on the exposed sections of the airframe and it doesn’t take long before the plane is going down, whether you like it or not. And if your windshield is still iced over when you break out of the clouds then you won’t be able to see anything as you try to pick out a place to crash. I don’t know, maybe it’s less scary that way. As I penetrated deeper into the clouds the layer of ice continued to build. Normally, the correct response to flying into icing conditions would be to immediately turn around. But I decided to keep going. I figured if the ice got too bad I could just descend to the warmer air over the Mediterranean where the ice would melt quickly. (Okay, “should” melt quickly.) It was a plan. Not a great plan, but a plan.

After being in icing conditions for fifteen or twenty minutes the wings had picked up about two inches of bumpy rime ice. The 182 had been slowed by twenty-five knots, but so far I was able to hold altitude. Suddenly, there was a sharp BANG from the front of the plane followed by intense vibration. … After landing I inspected the front of the aircraft and discovered the source of the vibration. The cone-shaped spinner attached to the propeller had a two-inch strip of metal missing around the edge of the propeller. The damage was probably caused by ice building up unevenly on the spinner, causing an imbalance. When it finally let go, it took some metal with it. I felt bad about the damage.

Flying over the maximum design weight is conventional.

At 25 percent over maximum gross weight, the heavy Cessna didn’t exactly leap into the muggy night air.

A night flight over the Sahara Desert doesn’t go as planned due to the failure of the single alternator:

I trimmed up the plane, engaged the autopilot, made a few navigation notes, then took out a Tom Clancy novel and tried to get comfortable. I was feeling fat, dumb and happy. A condition that lasted for about three hours. I was just starting to get into the groove of an all night flight when out of the corner of my eye I saw an ominous red light wink on. Curious, I leaned forward and read the words LOW VOLTAGE under the glaring red light burning on the instrument panel.

I pulled back on the yoke, climbing for a better look, and there laid out in front of me was what I’d been praying for all night, the city of Abidjan. I yelled out in joy at my luck. I’d flown 1800 miles over Africa, at night, with no electrical power and still managed to somehow find my way.

(Our hero author had been reduced to using dead reckoning, a compass heading, and a flashlight to see the attitude indicator (“artificial horizon”) for hour after hour.)

He ends up having to fly through a lot of thunderstorms, either because he’s already three-quarters across the Atlantic Ocean or because he’s over some African nations without good aviation infrastructures (GPS was new at the time that he was doing his flying and the Africans did not operate their VORs consistently).

“In reference to flying through thunderstorms; “A pilot may earn his full pay for that year in less than two minutes. At the time of incident he would gladly return the entire amount for the privilege of being elsewhere.” – Ernest K. Gann

My mood darkened as I stared out at the impressive light show laid out in front of me. I didn’t bother looking at the map for an escape path. I needed to go east and the storms were in my way. As I approached the storm wall I felt tiny and insignificant, like an ant at the base of a skyscraper. The boiling mass of dark gray towered above me, topping out at 40,000 … feet? … 50? … higher? The tops didn’t matter to me. I was heading for the middle. Tightening my seat belt I studied the flashing clouds, looking for a weakness. Not seeing any breaks in the wall I picked an area with the least amount of flashes, kicked off the autopilot and dove in. Strong turbulence slammed into the plane as soon as I penetrated the cloud wall, tossing me around like a rag doll. A strong downdraft made it feel like a trapdoor had opened beneath me. The little Cessna lost a thousand feet of altitude in just seconds. Loose items floated around the cockpit as I shoved the throttle to the stops and hauled back on the yoke trying to arrest the uncontrolled descent. In spite of my efforts I was still going down at fifteen hundred feet per minute. Then just as suddenly, an updraft grabbed the plane and pushed me down in the seat as the altimeter spun back the other way. This cycle repeated several times while lightning flashed around me like a crazy strobe light show. The sound in the cockpit was deafening as heavy rain pelted the windshield and airframe. I slowed my airspeed down as much as possible to prevent structural damage. (The words “in-flight breakup” echoed in my mind.) Holding a heading was impossible. Suddenly, I burst out of the clouds and found myself in clear air with massive thunderheads towered above me on all sides. The difference was incredible. One minute I was desperately fighting for control of the plane in severe turbulence, the next minute the air was smooth as glass.

Understanding systems is critical. When he can’t transfer fuel from the ferry tank that has replaced the back seats, he is able to figure out the problem and move 90 gallons of 100LL with lung power.

The owner was colorful:

On the leg from Bangor to Goose Bay, I heard two Canadian pilots from Quebec speaking French on the frequency Pete and I were using. The Canadian pilots were having a nice long conversation that was, I have to admit, kind of annoying. I knew if they were bugging me they had to be driving Pete crazy. One of the first things I learned about Pete was that there was a long list of things he hated: the FAA, customs officials, female pilots, stupid people, and, strangely enough for the owner of an international ferry company, foreigners, especially the French. … “Hey, why don’t you two learn to speak English?” Pete said over the radio. “FUCK YOU!” One of the French speaking pilots replied. Without missing a beat Pete replied, “Good! You’re learning!”

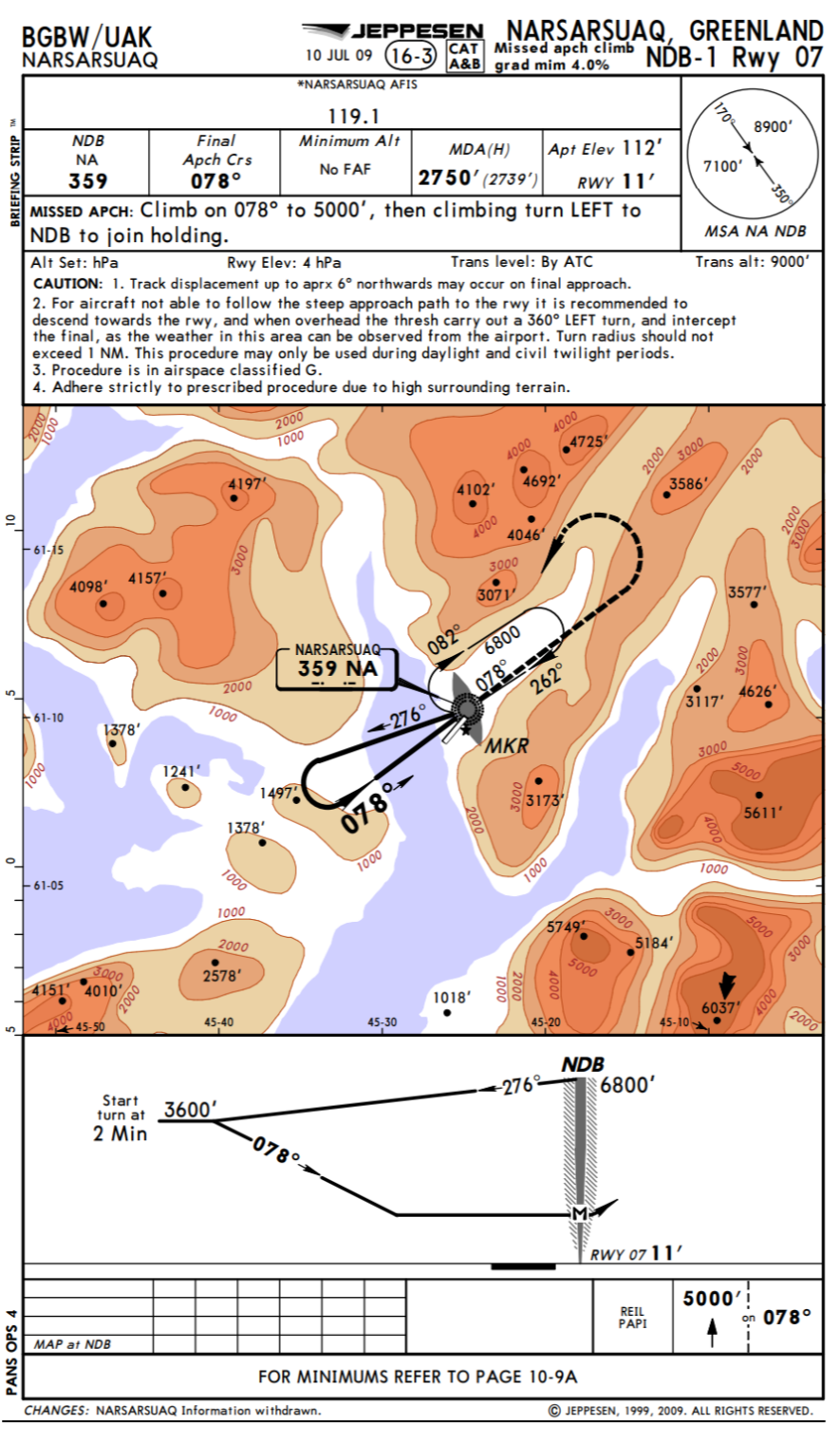

He describes the famous NDB approach to Narsarsuaq, Greenland:

The minimums:

Not for the faint of heart! (The GPS-based procedure is easier, but still gets one down only to 1700′ over the airport; a standard instrument approach at a flatland airport goes down to 200′ above the runway.)

Even though this was my tenth trip to Narsarsuaq, and Pete’s umpteenth, we were still slightly unsure if we’d picked the correct fjord until we saw the familiar sunken ship halfway in that marks the correct path.

#StopEskimoHate

After checking in to the Hotel Narsarsuaq, with its huge Polar Bear statue in the lobby, we headed to the Blue Ice Café for dinner. The food was fantastic and seeing that we were only flying about four hours to Iceland the next day, Pete and I decided to stick around and shoot a few games of pool. Meanwhile, the bar started filling up with local Inuit men and women. About ten o’clock the party started to get a little rowdy, and the Danish workers who were in the bar got up and left. The two airport employees we were talking to told us that they never stayed at the bar very late because the Eskimos who frequent the bar had a tendency to get roaring drunk, and fights broke out almost every night.

I can recommend FERRY PILOT: Nine Lives Over the North Atlantic to anyone who flies little planes (and the book is included for Kindle Unlimited subscribers). If you’re a Cirrus pilot you’ll gain a better appreciation for the redundancy that we do have: two alternators, two batteries, two or three attitude sources, a parachute.

Related:

- Amelia Rose Earhart, an American famous for a 2014 around-the-world trip in a Pilatus PC-12 (accompanied by a factory demo pilot)

- Around the world in 1964