How an asset bubble that inflates and deflates makes a lot of people worse off

One might think that an asset bubble that inflates and deflates doesn’t hurt that many people. After all, if you just stay in your house, what difference does it make if the value goes up to 3X and then comes back down to 1.2X?

Jeremy Grantham, the G in the asset management firm GMO, points out that people caught up in bubble fever adjust their consumption (i.e., spend like drug dealers). From his January 20 newsletter (a friend who has managed $billions sent it to me):

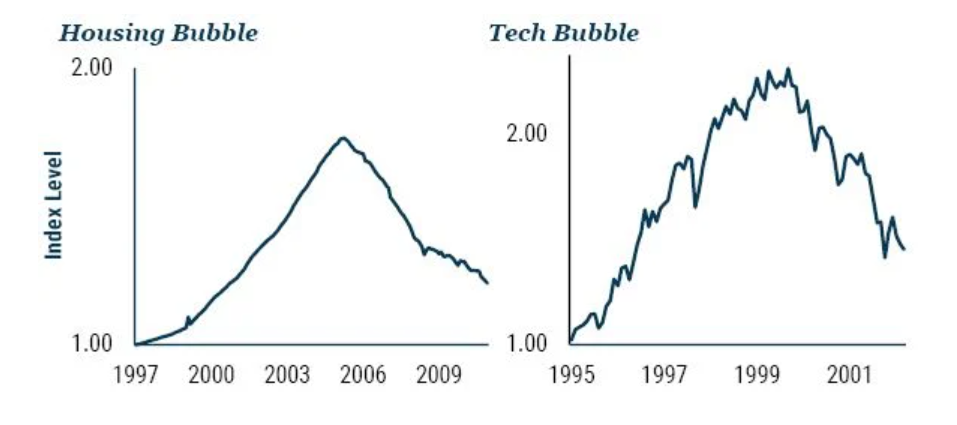

All 2-sigma equity bubbles in developed countries have broken back to trend. But before they did, a handful went on to become superbubbles of 3-sigma or greater: in the U.S. in 1929 and 2000 and in Japan in 1989. There were also superbubbles in housing in the U.S. in 2006 and Japan in 1989. All five of these superbubbles corrected all the way back to trend with much greater and longer pain than average.

Today in the U.S. we are in the fourth superbubble of the last hundred years.

One of the main reasons I deplore superbubbles – and resent the Fed and other financial authorities for allowing and facilitating them – is the underrecognized damage that bubbles cause as they deflate and mark down our wealth. As bubbles form, they give us a ludicrously overstated view of our real wealth, which encourages us to spend accordingly. Then, as bubbles break, they crush most of those dreams and accelerate the negative economic forces on the way down. To allow bubbles, let alone help them along, is simply bad economic policy.

What nobody seems to discuss is that higher-priced assets are simply worse than lower-priced ones. When farms or commercial forests, for example, double in price so that yields fall from 6% to 3% (as they actually have) you feel richer. But your wealth compounds much more slowly at bubble pricing, and your income also falls behind. Some deal! And if you’re young, waiting to buy your first house or your first portfolio, it is too expensive to get even started. You can only envy your parents and feel badly treated, which you have been.

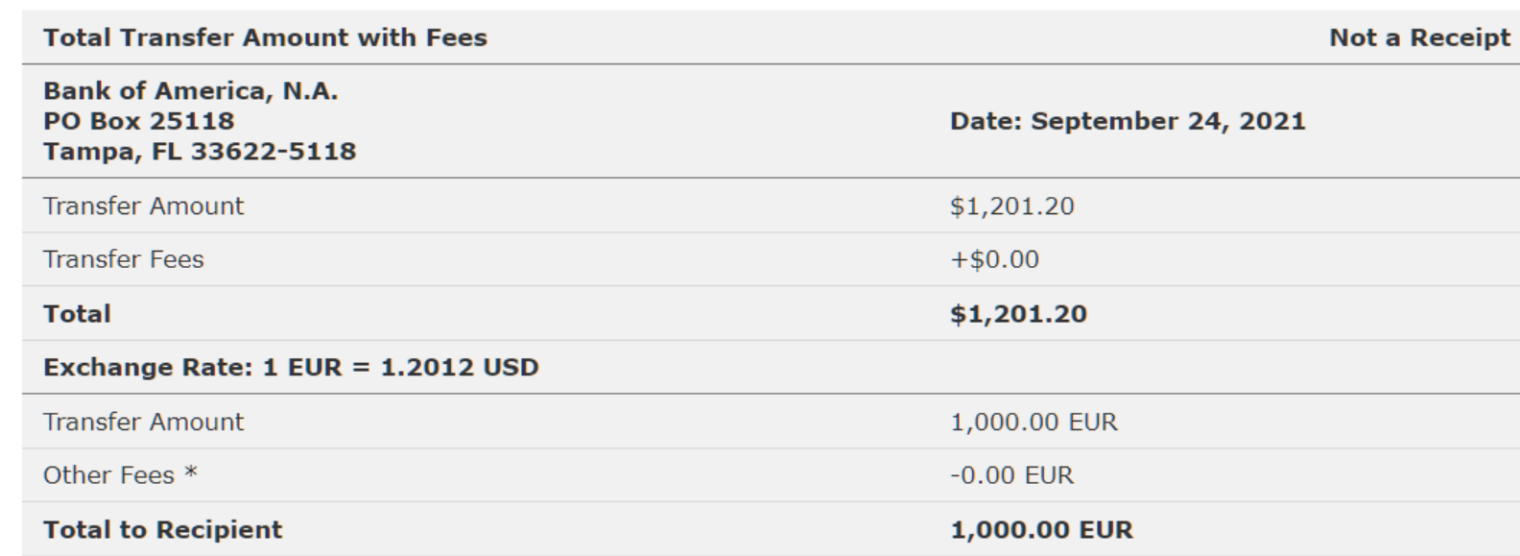

If your house goes from being worth $800,000 to $1.6 million, as the houses in our Florida neighborhood have done within the past two years, Grantham predicts that you’ll sign up for that lavish vacation, buy the fancy new car, splurge on clothing and jewelry (see “Cartier’s Dazzling Festive Season Bodes Well for Luxury Stocks” (WSJ): “Overall, U.S. jewelry sales increased 32% year-over-year from Nov. 1 to Dec. 24”), pay $1.2 million for a piston-powered unpressurized airplane, etc. We see this with governments as well. States that are raking it in from temporarily turbocharged capital gains taxes build new spending programs that will need to be funded every year, even if capital gains tax revenues collapse due to asset values stagnating (but maybe inflation can help, since capital gains tax calculations don’t adjust for inflation and, therefore, even assets that actually lost value will result in taxes being owed on a nominal profit).

Where does Grantham, an elder statements of the equity markets, think we’ll end up?

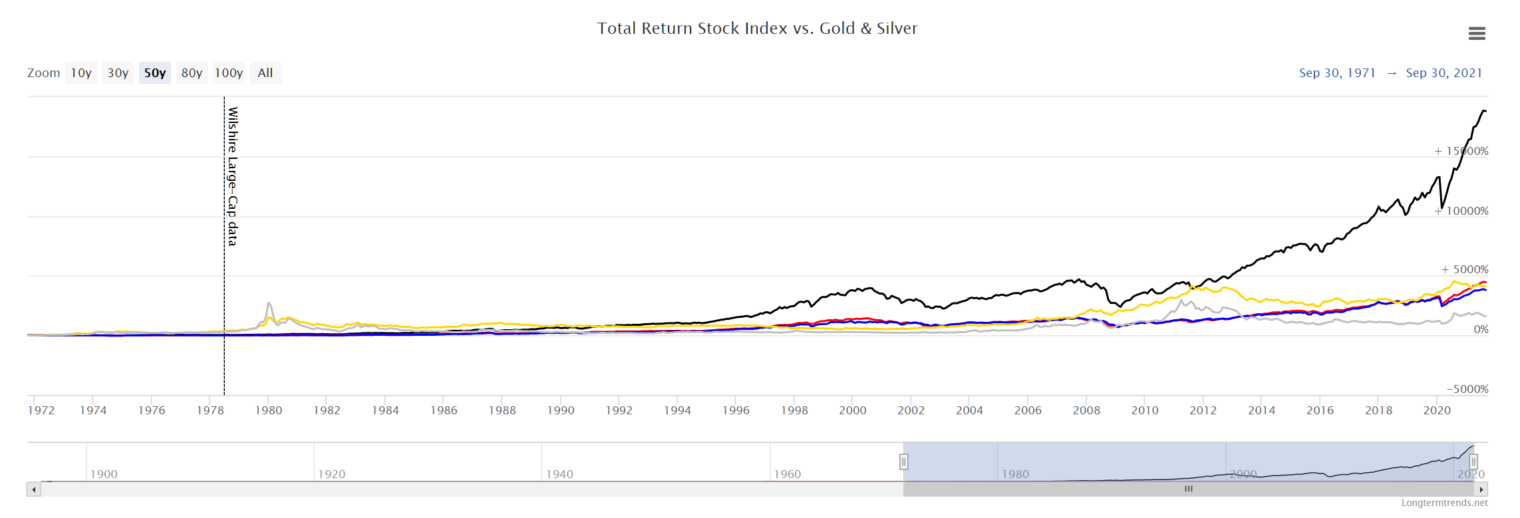

The key here is that two things are true: 1) the higher you go, the lower the expected future return; you can gorge on your cake now or enjoy it piece by piece into the distant future, but you can’t do both; and 2) the higher you go, the longer and greater the pain you will have to endure to get back to trend – in the current case to a trend value of about 2500 on the S&P 500, adjusted for the passage of time, from whatever high point the market might reach (currently at nearly 4700).

In other words, the S&P crashes to 2,500 or, assuming sufficiently clever manipulation of all the control wheels by wizards in Washington, D.C., stays more or less where it currently is, adjusted for inflation, for a decade or so.

(Maybe “spend like drug dealers” above isn’t the best expression for today? How about “spend like crypto early-adopters”?)

Related:

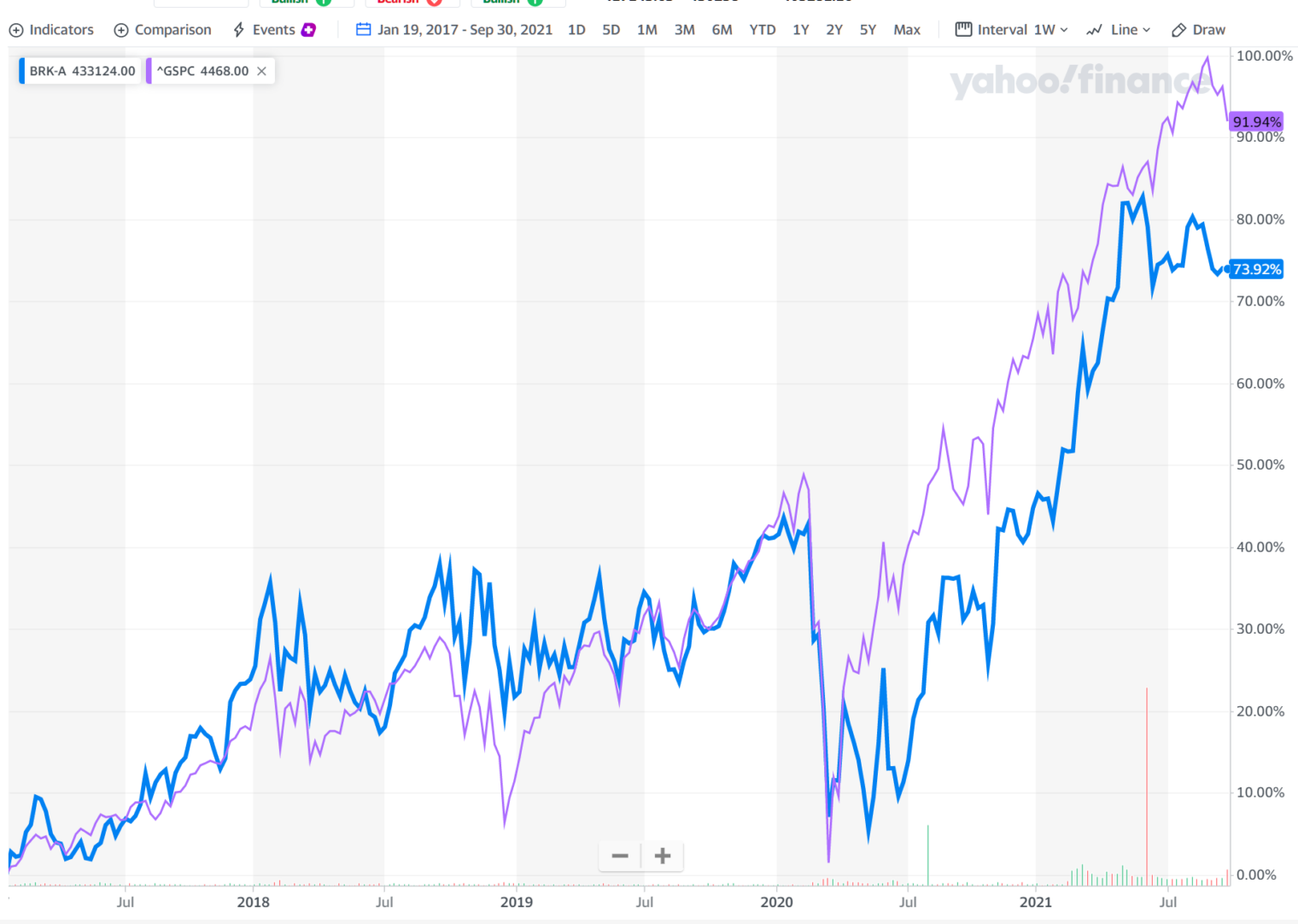

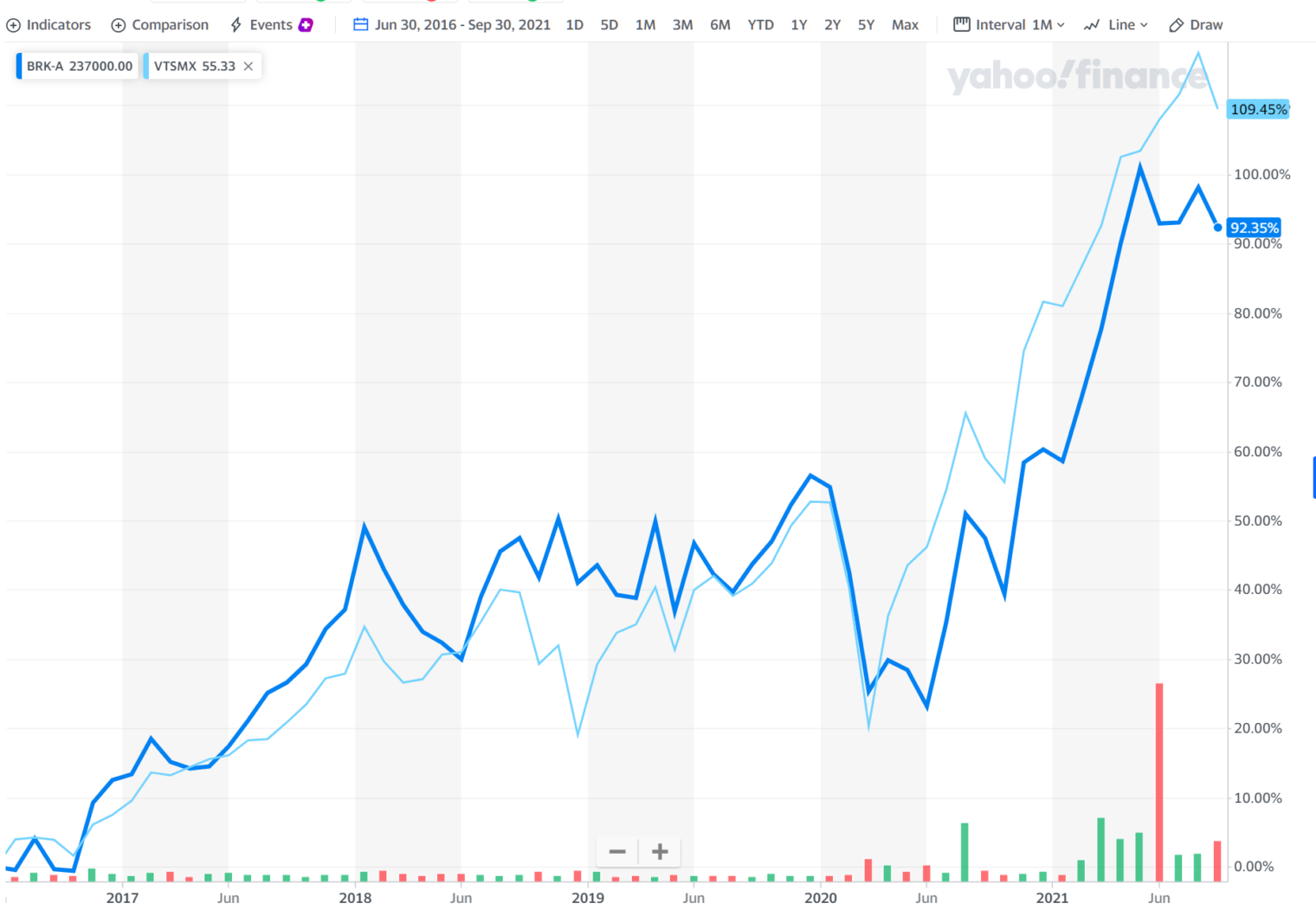

- Grantham warned us of a bubble in January 2021 (and if you’d followed his advice by going short or moving to inflation-savaged cash you’d be pretty miffed right now!): “We at GMO got entirely out of Japan in 1987, when it was over 40% of the EAFE benchmark and selling at over 40x earnings, against a previous all-time high of 25x. It seemed prudent to exit at the time, but for three years we underperformed painfully as the Japanese market went to 65x earnings on its way to becoming over 60% of the benchmark! But we also stayed completely out for three years after the top and ultimately made good money on the round trip. Similarly, in late 1997, as the S&P 500 passed its previous 1929 peak of 21x earnings, we rapidly sold down our discretionary U.S. equity positions then watched in horror as the market went to 35x on rising earnings. We lost half our Asset Allocation book of business but in the ensuing decline we much more than made up our losses.” The Jan 2021 piece includes the figure below.