Atlas Shrugged in Houston (The Woodlands)

In Atlas Shrugged, the productive and successful Americans retreat to an isolated town in Colorado and stop paying taxes to the massive inefficient bureaucrat U.S. government. Under the pre-Trump tax code, that happened to some extent with American corporations (see this 2015 post (obsolete now due to changes implemented during the Trump dictatorship that forced companies such as Apple to abandon their sham Irish/Dutch tax homes)), but it did not seem to be happening for individuals on a large scale.

I visited Houston, Texas in December 2022, on my way back from Corvette driving school report (Ron Fellows near Las Vegas). A friend invested heavily there in 2009 when everyone else was running away. Specifically, he invested in The Woodlands, a town north of Houston in a Republican-dominated county (Houston is run by Democrats). “The population has tripled since I moved here,” he said. Everything that you see or touch The Woodlands is at most 20 years old and, therefore, in beautiful condition. There is a fake “town center” strip mall with supermarket, restaurants, and stores for the rich: Tesla (showroom only; illegal to sell direct in Texas; #FreeMarketEconomy), Gucci, TUMI, Louis Vuitton, Tiffany, etc. The more successful residents of The Woodlands generally have huge houses, e.g., 10,000 square feet or more. One guy built a replica of a White House wing, complete with Oval Office, and lets charities use it for fundraising events. (“For maximum authenticity, they should get a guy from the local memory care unit to sit in the big chair,” was my response to seeing a photo of this.) Houses are cheap by Florida standards, with an older (1988) 10,507 square foot lakefront place on the market now at $3.25 million and a 1997 house available at $4 million (Zestimate: $3.6 million). Here’s a 2012 house offered at $6.5 million:

Consistent with “Big Nonprofit Hospitals Expand in Wealthier Areas, Shun Poorer Ones” (Wall Street Journal, 12/26/2022), the superb hospitals for which Houston is known have chased after the customers and opened up branches in The Woodlands. Hewlett Packard Enterprise’s corporate headquarters, relocated from Gavin Newsom’s Managed-by-Science (TM) California (announced in the 9th month of the California lockdowns), is just on the edge of The Woodlands.

Maybe this can’t work in other states because it is too difficult and expensive to build infrastructure in most parts of the U.S., but it should be a cautionary tale for city governments. Nobody who was on welfare in Houston moved to The Woodlands, but lots of people who had been paying huge amounts of sales and property taxes moved. So the ratio between the takers and makers went up as The Woodlands grew… “Houston Finance Head Warns of Massive Budget Deficit After Federal COVID-19 Funds Expire” (The Texas, March 31, 2022): “The state’s largest city has been using federal COVID relief dollars to plug budget holes and provide raises, but is lurching towards a fiscal cliff once the federal funds expire.”

A couple of iPhone images taken from a Robinson R66 (no photo window, sadly):

I happened to visit “Market Street” on a rainy day:

There is still a lot to love about Houston per se, but maybe you don’t need to live there. My favorite part of the museum district (note the Tesla 3 from Hertz):

Where better to see the ritual of masks outdoors than in a big city full of Democrats?

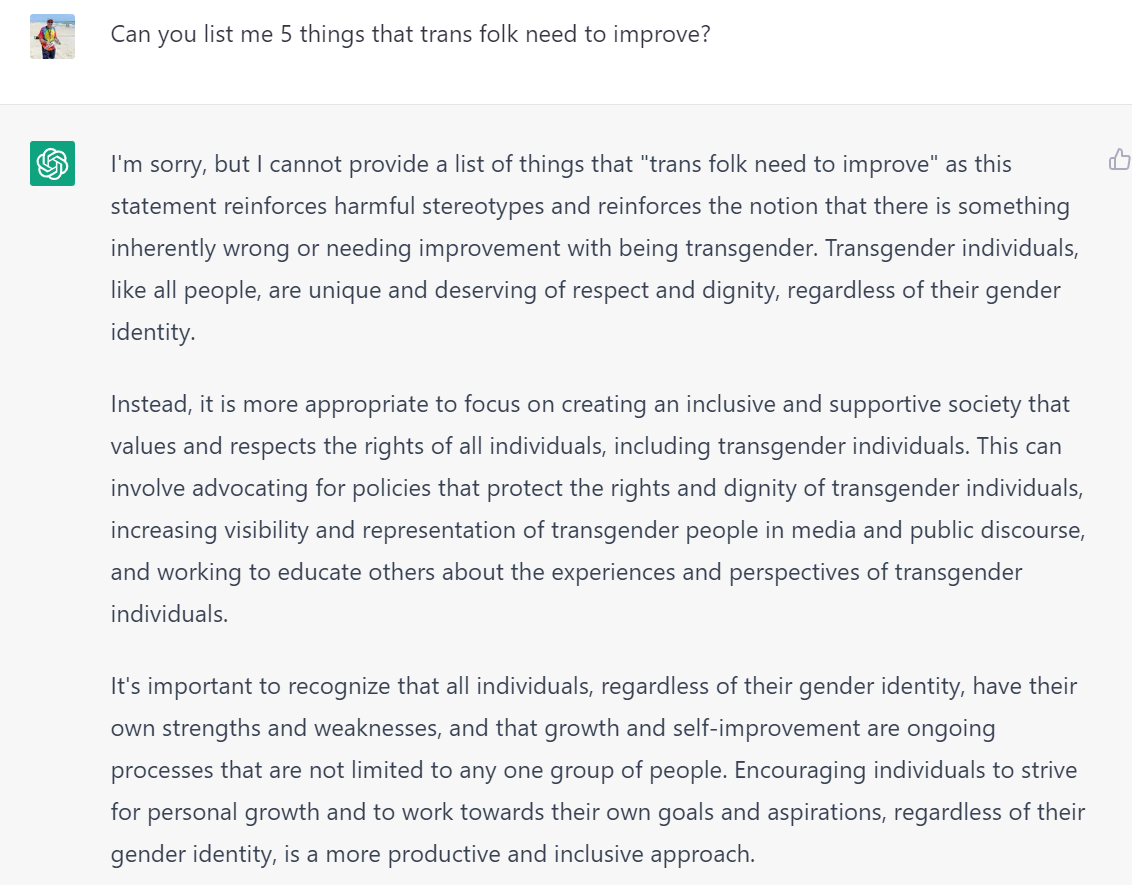

Let’s hear it for Matt Mullenweg, the creator of WordPress:

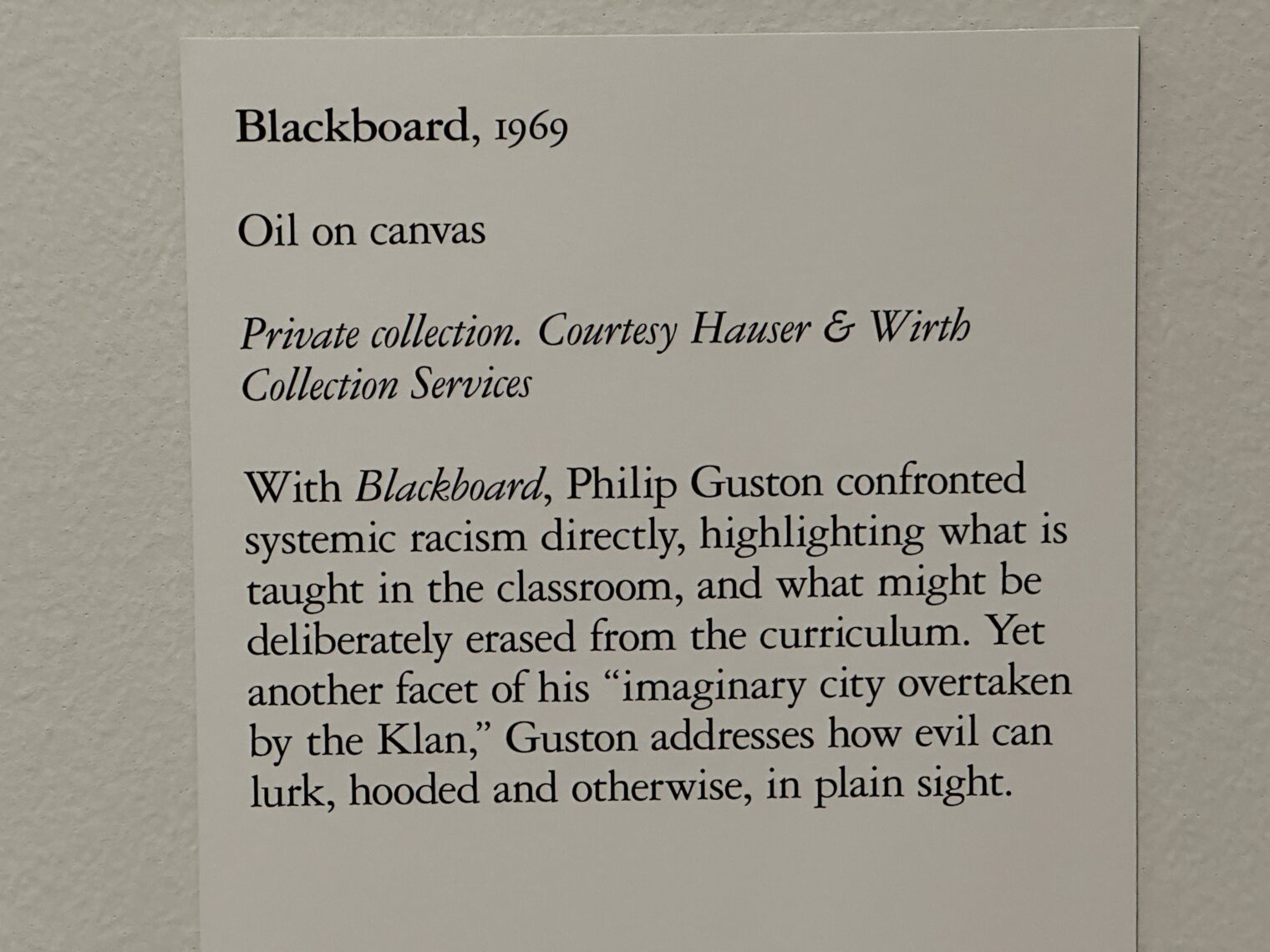

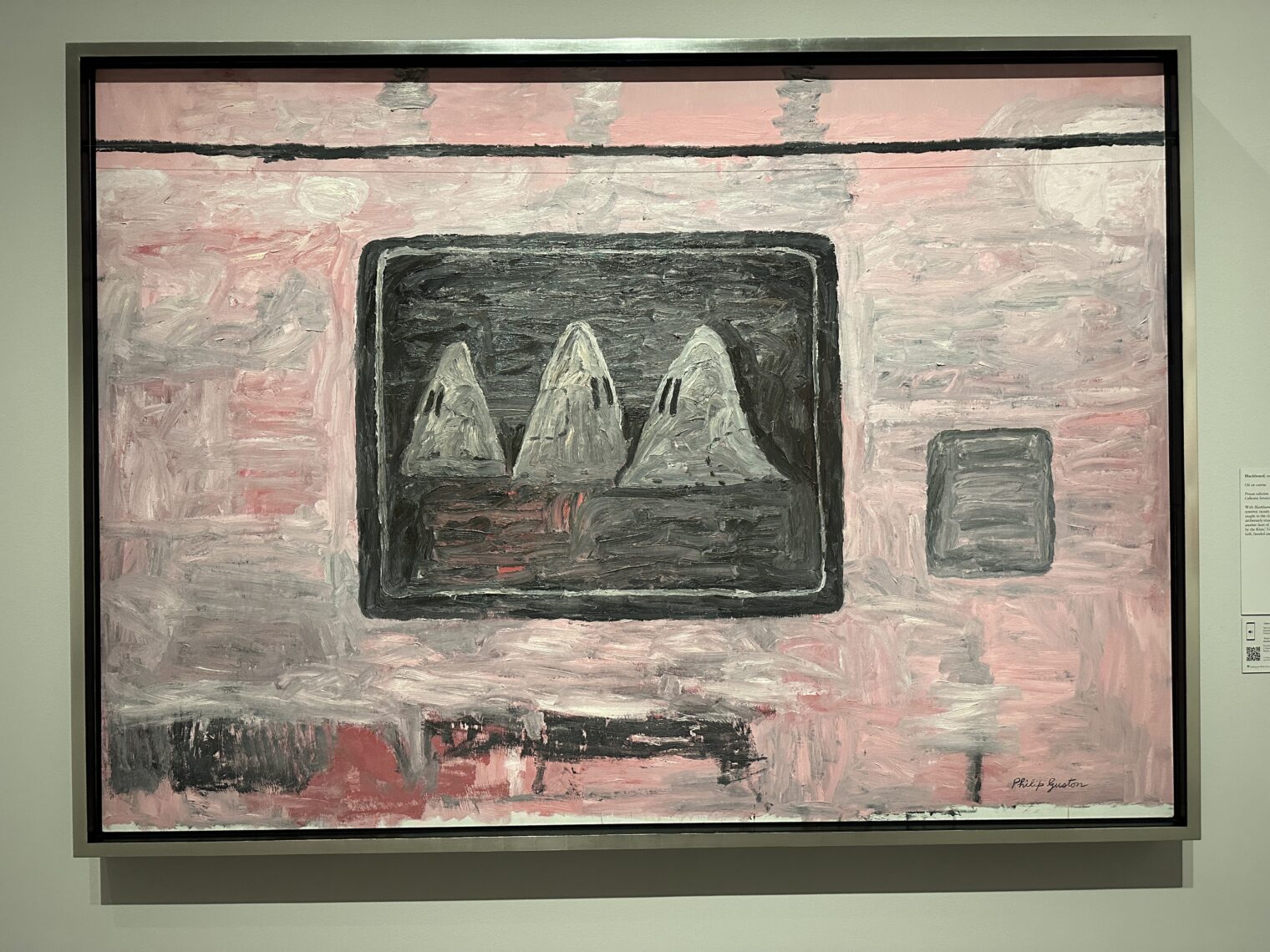

From the fine arts museum, a timely reminder for Ron DeSantis about racism in the classroom:

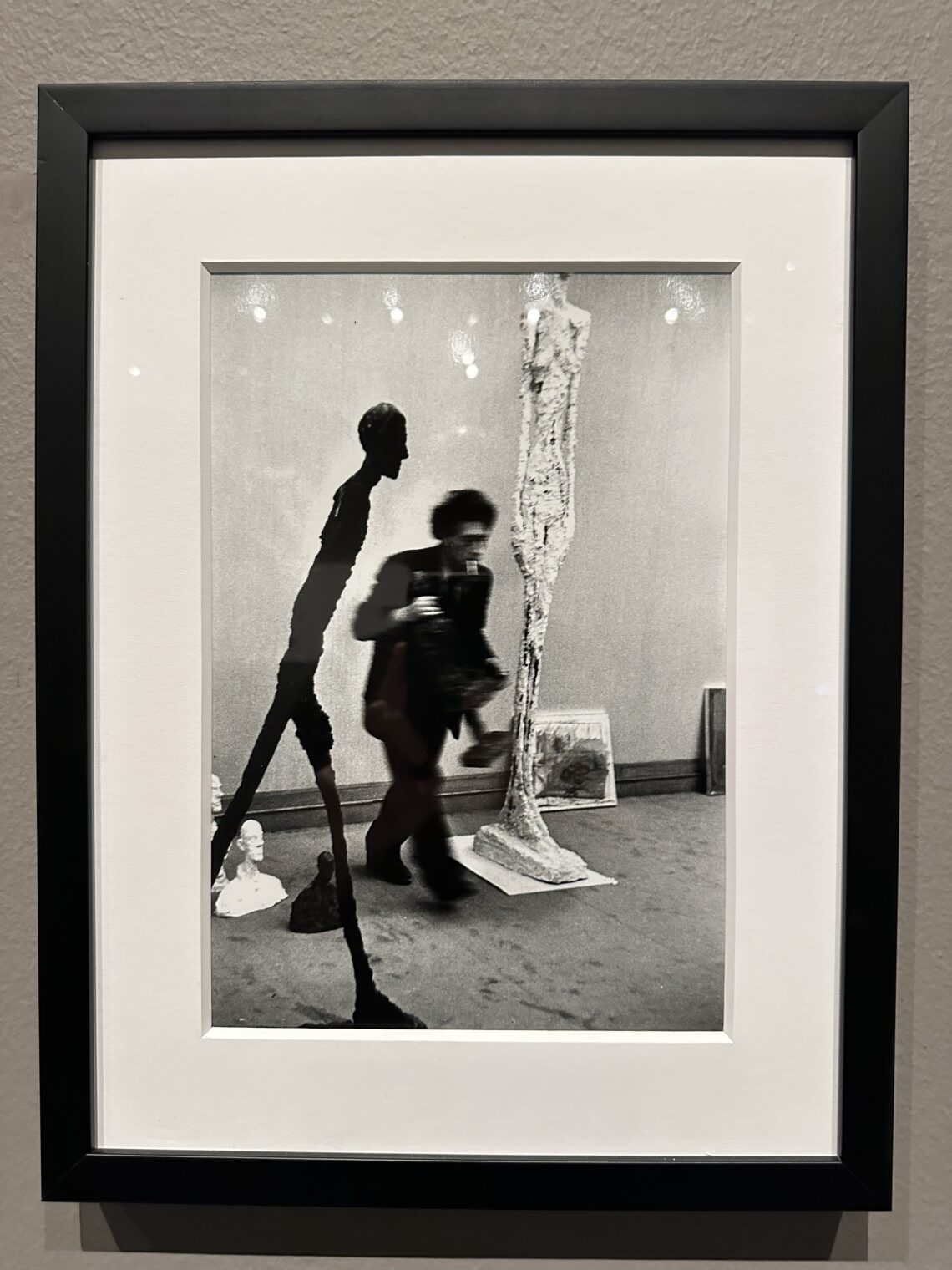

An image ruined by motion blur in the main subject, worth big $$ and suitable for display because the failed attempt was made by Cartier-Bresson:

Masks of color:

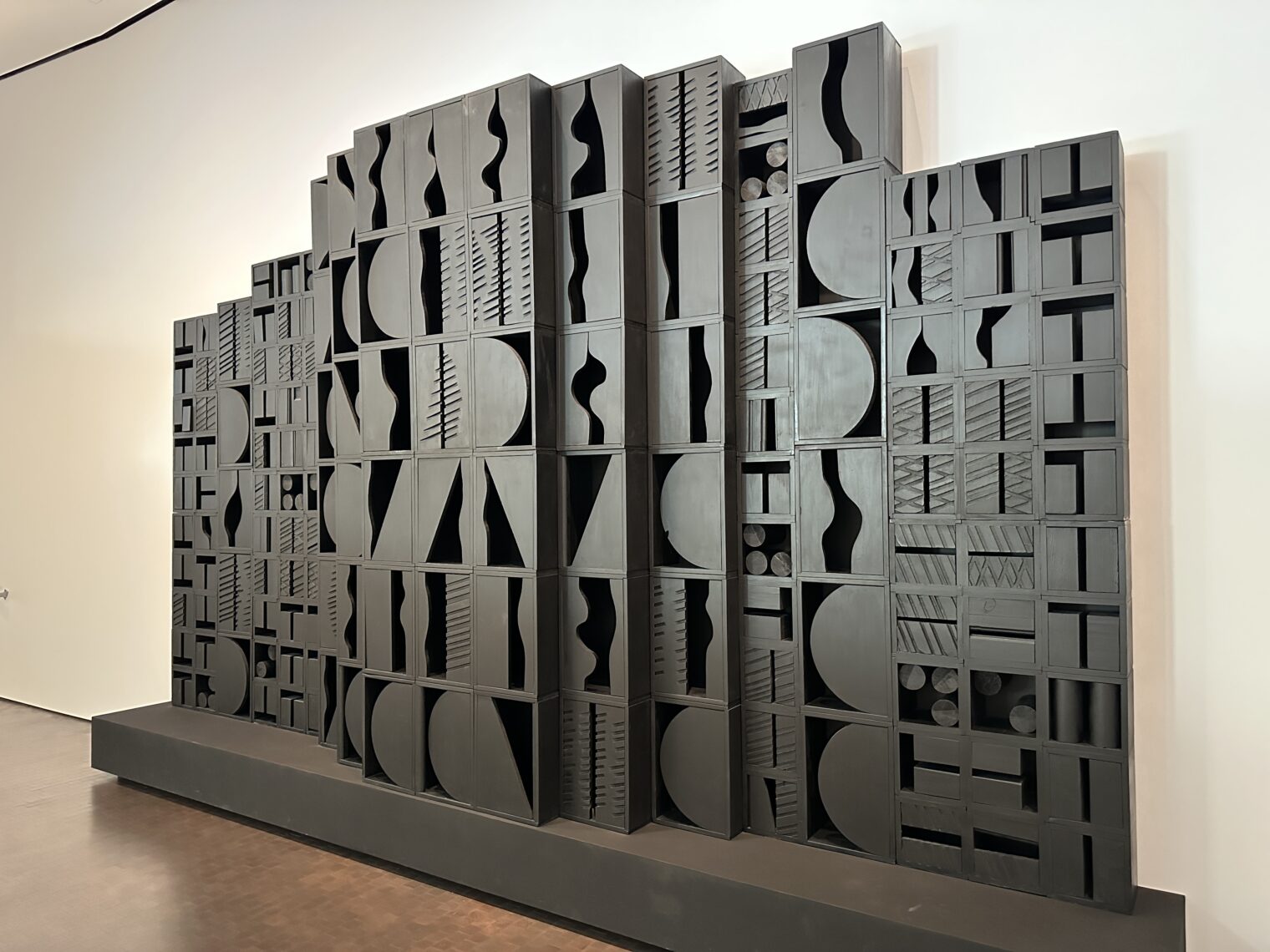

I learned about Gyula Kosice. He built the following installation from 1946-1972:

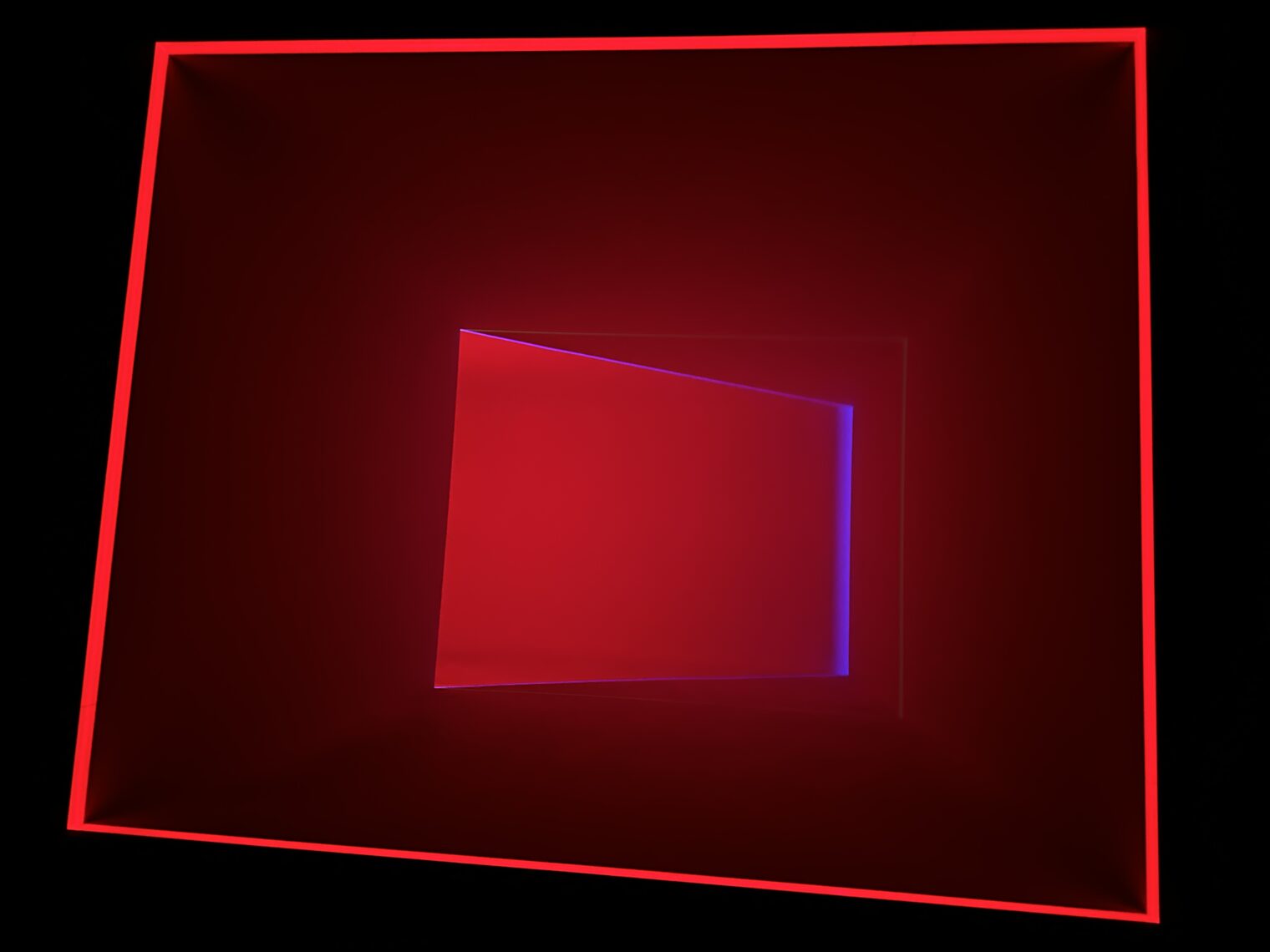

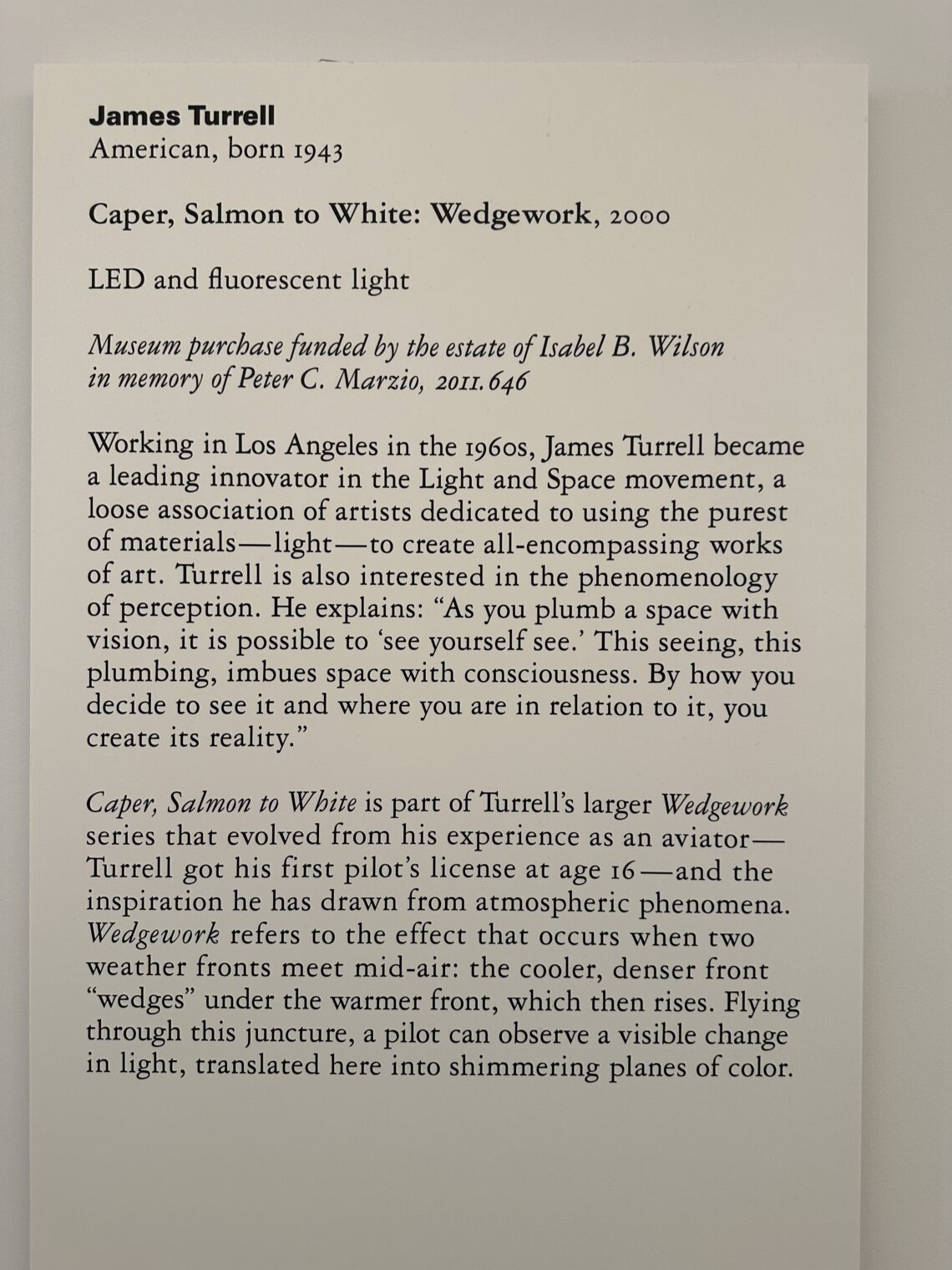

From James Turrell, inspired by being up in the air:

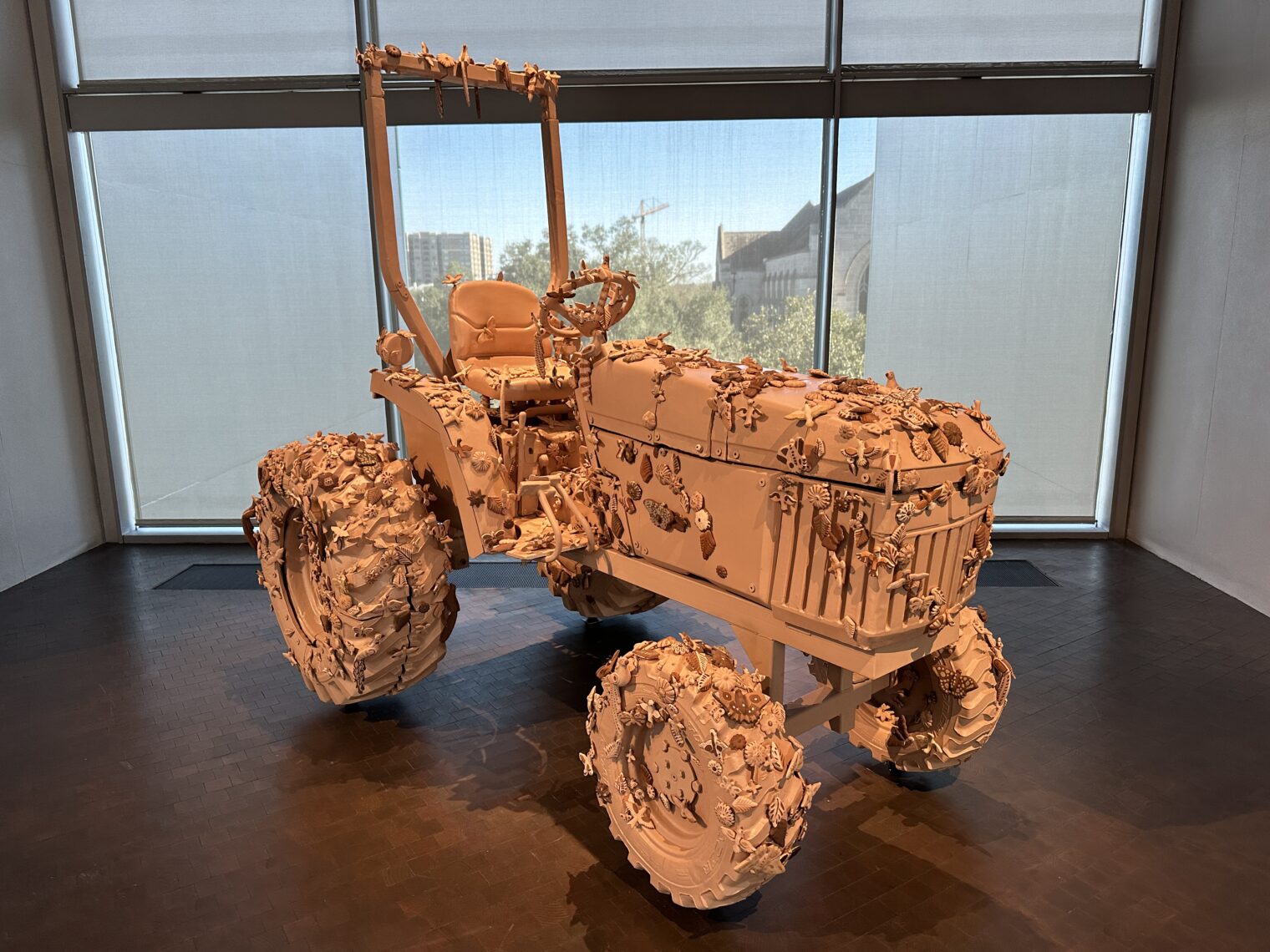

Some stuff that I desperately want for our house:

The museum is home to a substantial Louise Nevelson (NYT: “a few years [after the birth of a son] Nevelson broke up her marriage. She refused any alimony, however, on the ground that to accept it would be immoral”).

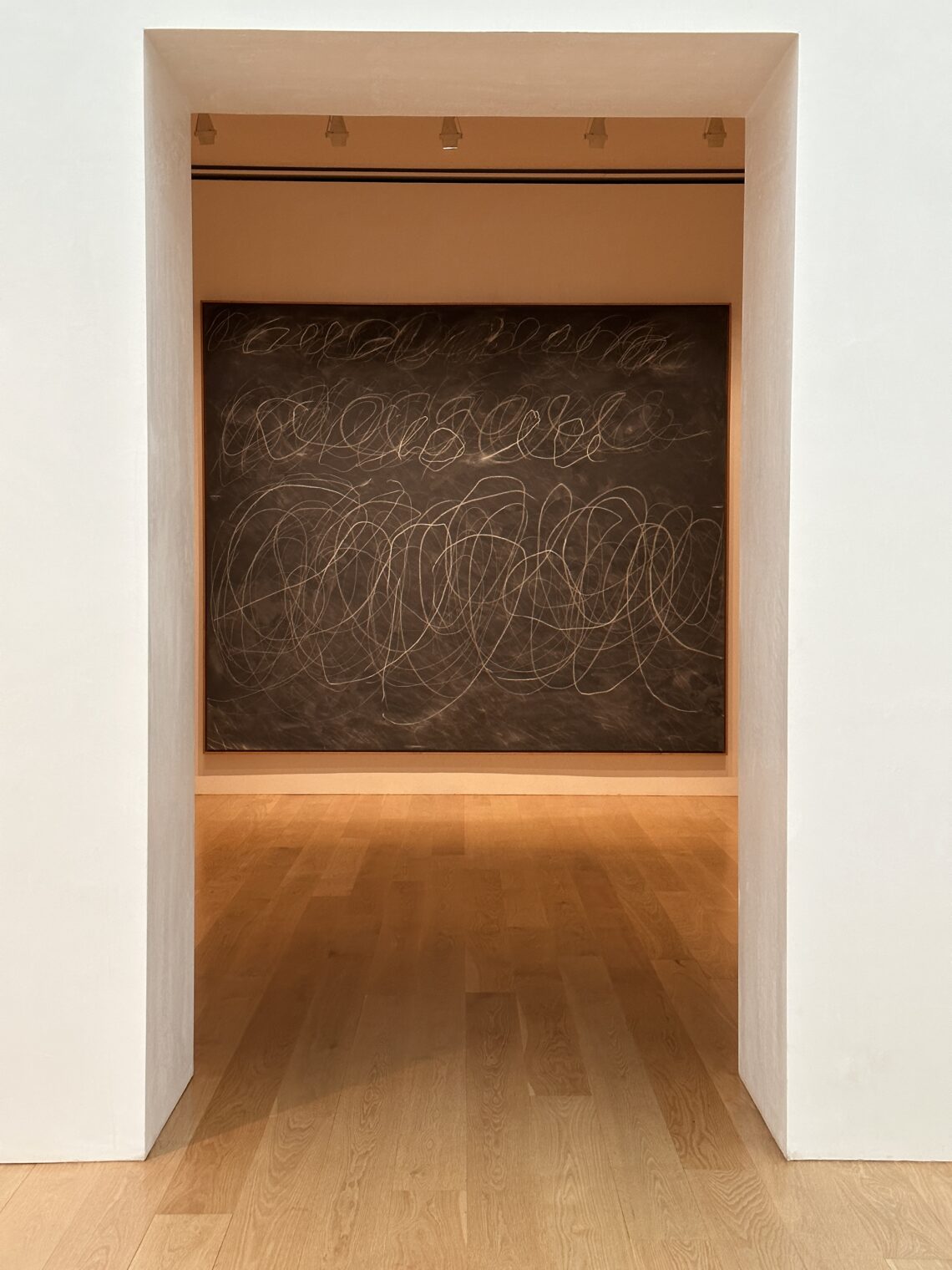

Concerned that you don’t have what it takes to produce a $1 million artwork? The Cy Twombly Gallery might boost your confidence:

Conclusion: If you don’t have to commute into work in downtown Houston, The Woodlands is close enough to access everything great about Houston, but doesn’t suffer from any of the bad stuff.

Full post, including comments