Define irony: Private school hosts diversity, equity, and inclusion event at a country club

Garland Greene:

Define irony – a bunch of idiots dancing around on a plane to a song made famous by a band that died in a plane crash.

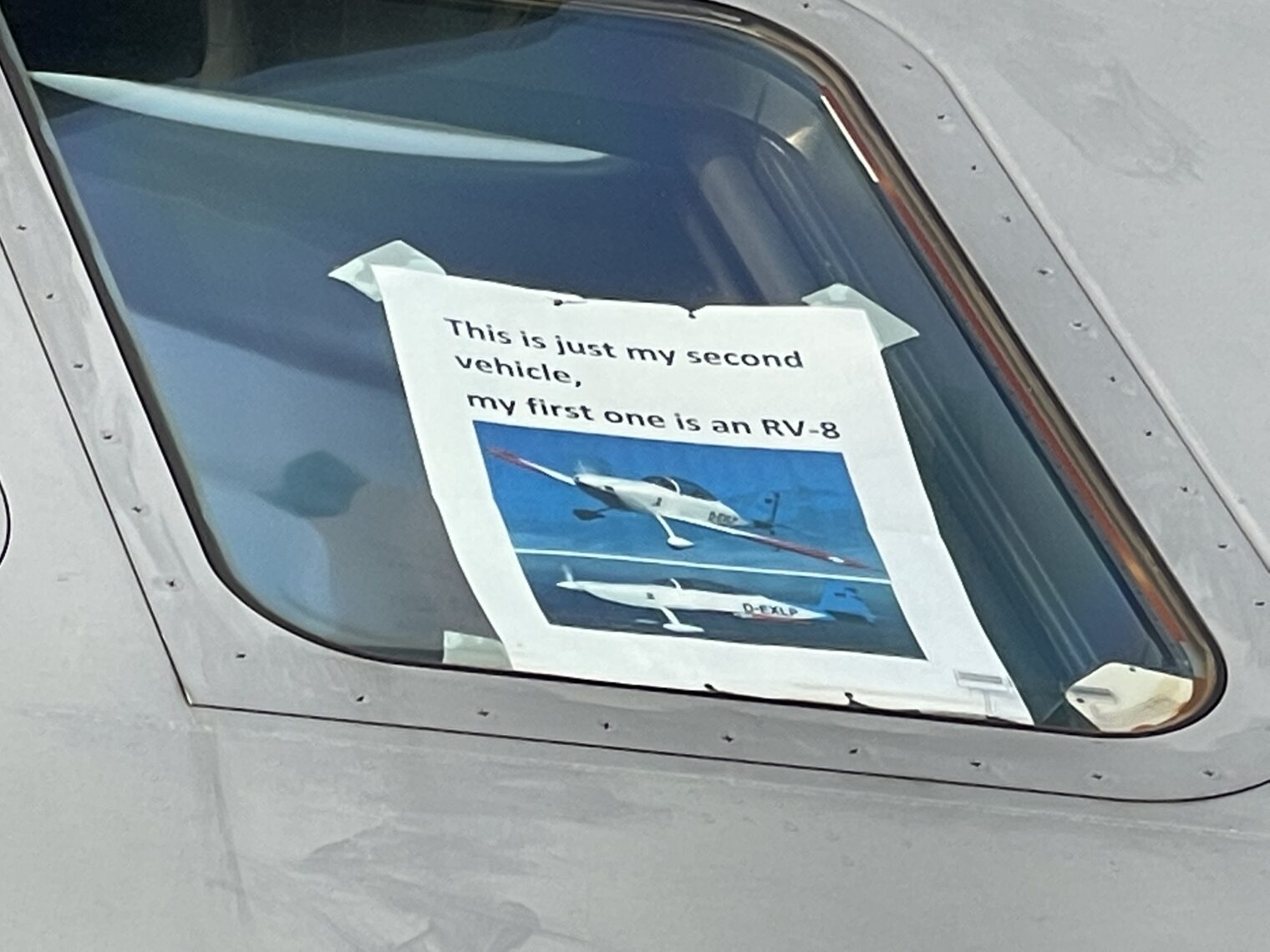

I would like to propose an update to this philosopher’s work. #DefineIrony: We were invited to an exclusive (and expensive) private school’s diversity, equity, and inclusion event… at a country club.

Related, from Saturday Night Live, April 9 1977…

Julian Bond: Well, this is the major problem with these studies. The measurements of I.Q. which form the basis of comparison come from tests composed by whites for whites. The tests are culturally biased; it’s not surprising that whites would score better than blacks.

Garrett Morris: Could you give us an example of what you’re talking about?

Julian Bond: Certainly. Here are some questions that have appeared on recent I.Q. tests. Number one: “You have been invited over for cocktails by the officer of your trust fund. Cocktails begin at 4:30, but you must make an appearance at a 6:00 formal dinner at the Yacht Club. What do you do about dress?

A. Wear your blue-striped seersucker suit to cocktails and change into your tuxedo in the bathroom, apologizing to your host for the inconvenience.

B. Wear your tuxedo to cocktails, apologizing to your host for wearing a dinner jacket before 6:00 PM.

C. Walk to the subway at Columbus Circle and take the “A” Train uptown.”