Bartleby, the Divorce Plaintiff: A Story of Wall-Street

What if a man could look at all of the tasks required by the roles of husband and father and, like Bartleby, the Scrivener, simply say “I prefer not to”? That’s the story in Strangers: A Memoir of Marriage by Belle Burden. Her husband “James” is pseudonym for Henry Patterson Davis (nytimes 1999 wedding announcement) who was completely unashamed of abandoning the wife and kids to the point that he gave the author explicit permission to publish her tale in the New York Times and as a book, knowing that anyone with access to Google could trivially discover his real name and that they Daily Mail would run headlines like this:

For most of the no-fault divorce era in the U.S. (1970s onward), men have been kept in their place by a family court system that will ruin them emotionally (give the kids to the mom) and financially if they attempt to throw over the traces. Our laws are nominally gender-neutral, however, and women who have a higher income than their husbands have been vulnerable in recent decades to losing divorce lawsuits and writing monthly checks to enable their former spouse to enjoy sex with younger women (see “More and More Women Are Paying Alimony to Failure-to-Launch Ex-Husbands. And They’re Really, Really Not Happy About It.” (Washingtonian 2021)). Bell Burden’s book is about a wife who is moderately rich via inheritance/trusts but who quit her career and thus earns much less than her husband. His financial exposure in a divorce was limited by a prenuptial agreement keeping most of their finances separate (this can be the default in Germany by checking a box on the marriage license application). The family court system in Northeastern states is premised on the assumption that fathers don’t care about their children, are incapable of caring for children, and that their only valid role is financial support of the mother of the children (who can decide to spend some of the money that she receives on the kids, if she so chooses). Strangers: A Memoir of Marriage answers the question, “What happens if a white man with money acts in accordance with court system expectations?”

While married, “James” stays in harness, laboring like a Latinx landscaper:

In 2008, Susan bought us an eight-acre plot of land adjacent to our house. We wanted to secure our privacy and have space for the kids to build houses as adults. The new plot was all forest—oak trees, pine trees, brush. James was entranced with it. He created winding paths, pruned trees with a long pole saw, and sprayed every weekend for poison ivy, wearing a Roundup backpack with a nozzle. He said it would take him many years to make the paths perfect for the girls’ weddings. He imagined walking them through the woods to a small beach on the lake, steps from the osprey pole. He named the beach for Finn, and carved Evie’s initials in a fallen tree trunk beside the boardwalk. He found boulders in the woods and named them for each kid, the biggest for Carrie. He taught them how to find their rocks using his carefully tended paths.

He kept investing in our Vineyard imprint, year after year. In 2018, he designed a large addition to the garage to house his extensive collection of motorcycles and forestry equipment. He included a garden on top of the addition for me, raised beds we filled with herbs and tomatoes and flowers. In 2019, he planted blueberry and raspberry bushes on the edge of the property, plants that take several years to bear fruit.

As of 2019, in other words, he was investing time in a house that belonged to the wife (purchased with her family trust funds) whom he was soon to sue. The Covidcrats felt free to reevaluate all assumptions that Americans had about life, e.g., whether children had the right to attend school and adults had the right to congregate in churches or at work. Perhaps this gave “James” a mental nudge to question long-held assumptions. Regarding continued sex with a 50-year-old mom and continued hands-on responsibility for housing, feeding, and talking to adolescent children, “James” never said that there was anything wrong with married life, but only “I prefer not to continue with this life.” After the wife learns about her 35-year-old competitor:

He said, “I thought I was happy but I’m not. I thought I wanted our life, but I don’t.” He said, “I feel like a switch has flipped. I’m done.” He said, “You can have the house and the apartment. You can have custody of the kids. I don’t want it. I don’t want any of it.”

The author, her friends, and various mental health professionals were all shocked by this Bartleby-like behavior.

My stepmother, Susan, called me several times a day. We were very close, bonded from the moment she entered my life in 1972. She wept with me, both of us quiet as we cried. She was the only person who tried to reach James. She emailed him in the second week, writing that in her forty-five years of practice as a family therapist, she had never seen someone leave a marriage so cruelly. She begged him to speak to me, to do therapy with me, to try to end the marriage kindly, honorably.

[an elite neighbor on the Vineyard] leaned forward and raised both his hands, his palms facing me. He said, “I want you to understand that what James is doing is wrong. The way he left you without explanation is wrong. Walking out on his family during a global pandemic is wrong. The way he is treating you now is wrong. If he tells you it isn’t, if anyone tells you it isn’t, don’t believe them.”

[a psychiatrist] was blunt and, like the husband from overseas, she offered clear opinions. It was wrong to leave a marriage with no warning and no explanation. It was highly unusual not to want custody of kids who were as young as twelve. It wasn’t normal to search the basement for a prenup after telling children about a divorce.

A year later, the husband/plaintiff doesn’t have a more detailed explanation than “I prefer not to”:

I wrote, “You never told me what I did wrong in our marriage, why you stopped loving me. It is such an awful thing, after twenty-one years, not to know.” I had hoped something had changed, that he would give me the answer, the lost frames of the movie, something to help me understand what had happened. He wrote back, “I wish I could answer your question, something broke in me, it was me and not you, you did nothing wrong.”

Any life lessons from this book? The Martha’s Vineyard tennis club is jammed with women who have fancy degrees, but choose to not work. I.e., instead of marrying 30-year-olds with professional degrees, the men could have married 20-year-old yoga instructors and ended up with the same household income and many more kids.

The women were universally well-educated, but most, like me, had left the workforce. This felt good; in New York, I felt conflicted, and embarrassed, about having paused my legal career. I didn’t feel this way on the Vineyard, surrounded by smart women who had made the same choice.

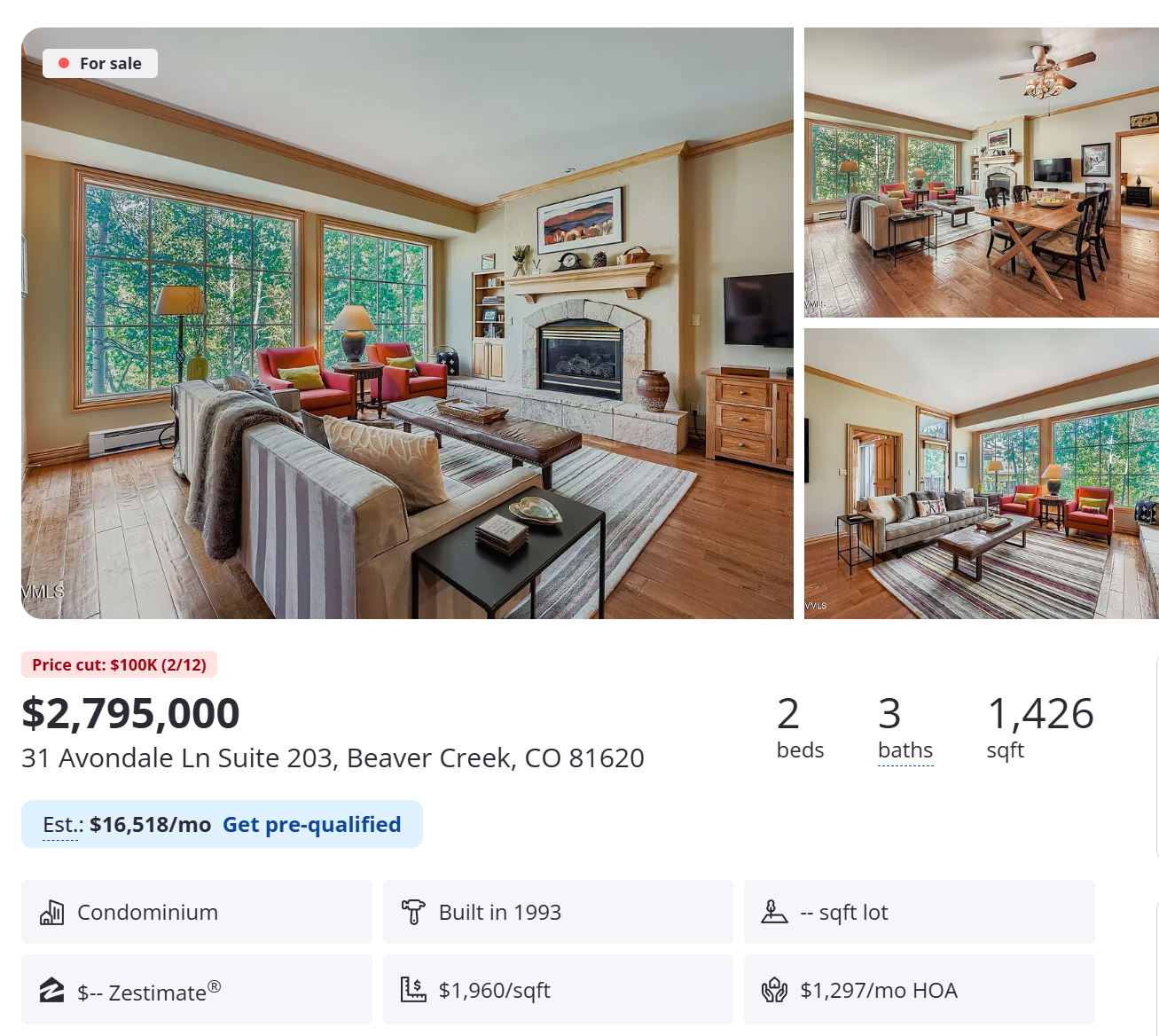

One important lesson from the book is that people shouldn’t take money out of trusts to spend on real estate. A big point of leverage that “James” had over Belle was that she’d actually paid for their apartment in Manhattan and their house on the Vineyard with her trust funds. The prenup, however, technically gave the plaintiff the right to take half of the value out of both properties. Ultimately, there was a settlement, but perhaps the wife would have done better if her trust had owned both properties rather than her holding them in her own name or them being jointly titled. If you want to protect your kids from future family court predators, therefore, set up their trust so that the trust can buy and own property and the kids have the right to use it.

Full post, including comments