Non-profit logic: higher prices make the museum more accessible

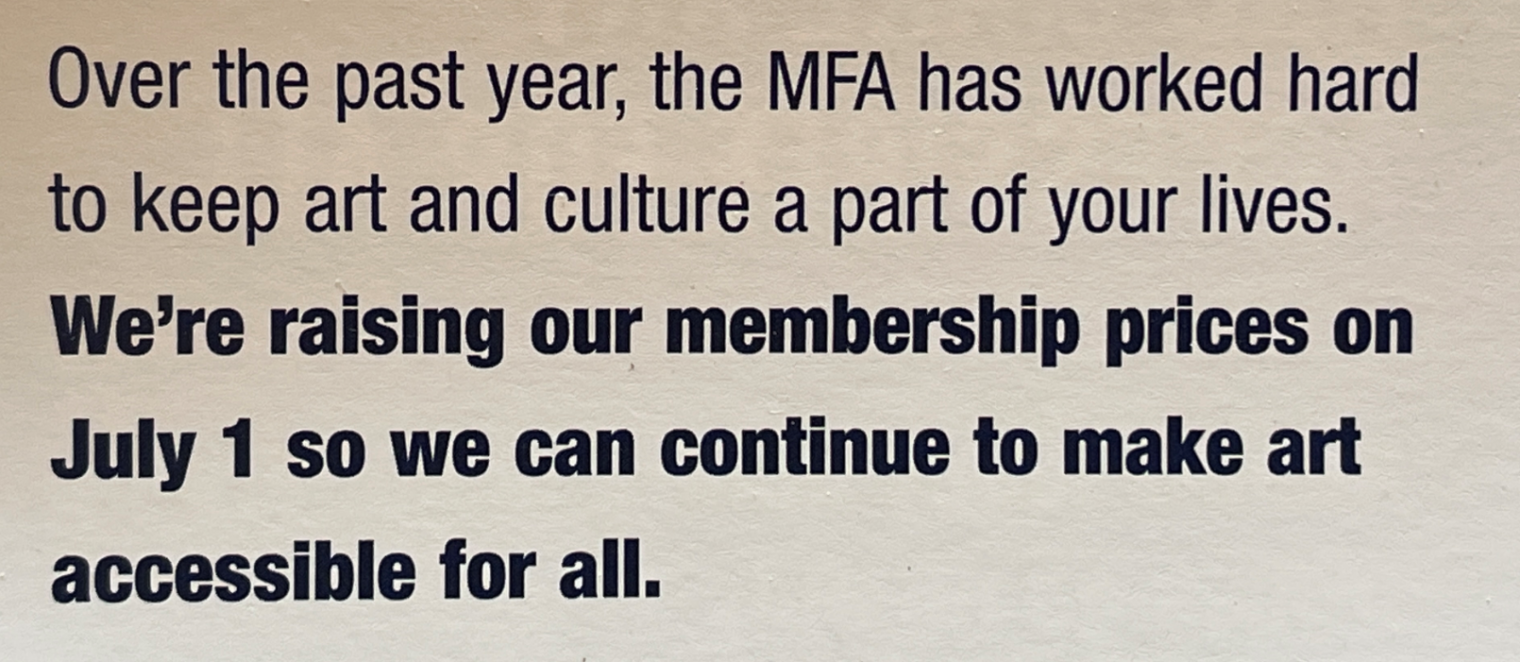

From the Boston Museum of Fine Arts:

(“We’re raising our membership prices on July 1 so we can continue to make art accessible for all.”)

So a middle-class family that wants to visit the museum regularly and not pay $50 per visit (two adults) will find art more accessible when annual membership is more expensive!

Separately, if you ever need someone to run an Ebola clinic, the MFA should be the first recruiting stop. We visited on February 19, 2021 and they’d set up a quarantine tent outside the front door. About six people were employed to check the handful of visitors to make sure that they had reservations, that they answered a bunch of COVID-19 symptom questions, that their temperature was checked, and that they donned orange wristbands to show that the screening process had been accomplished and they couldn’t somehow slip into the building without first going through the quarantine tent.

Once inside, the vast spaces had a post-apocalyptic empty feeling.

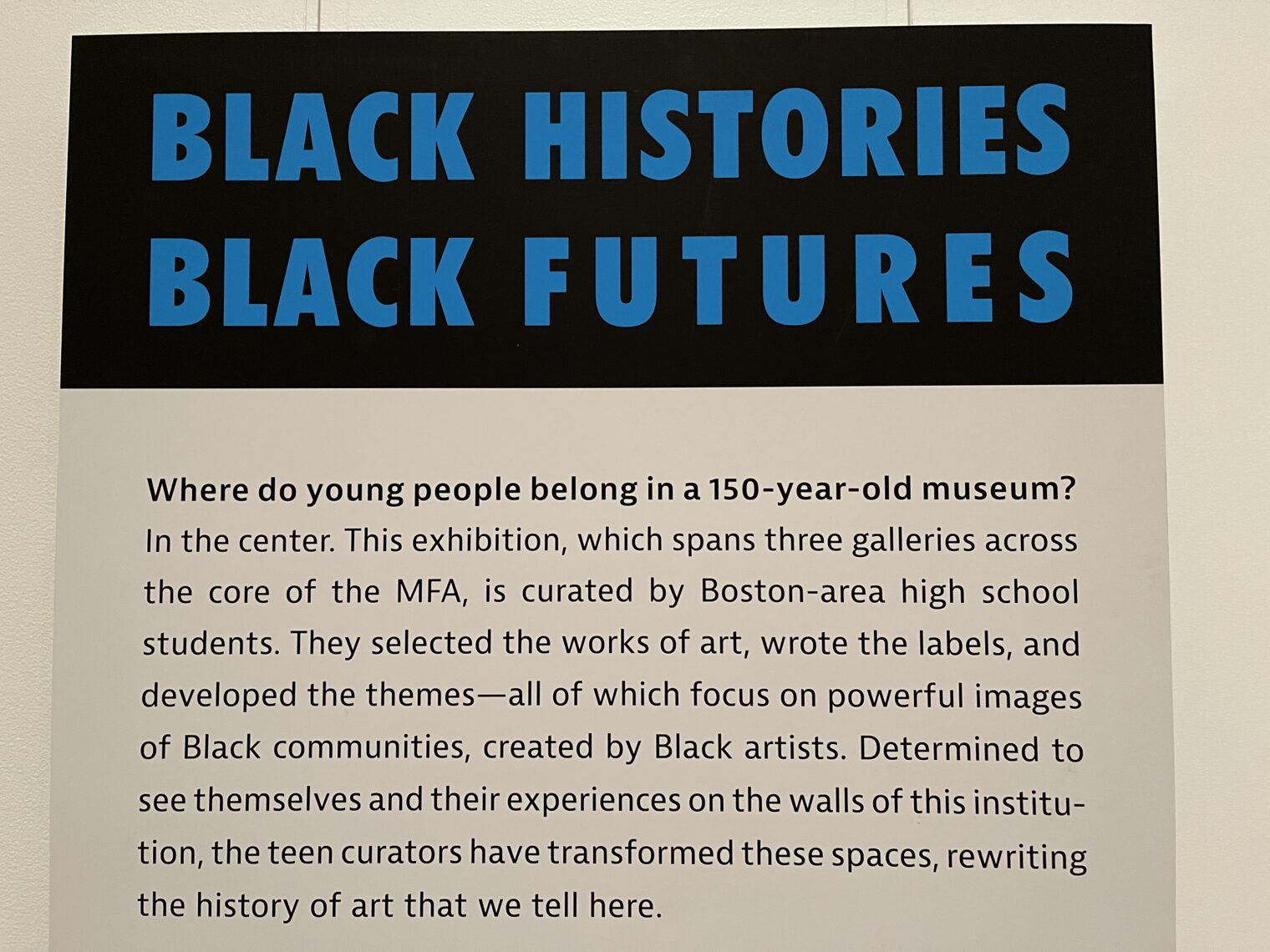

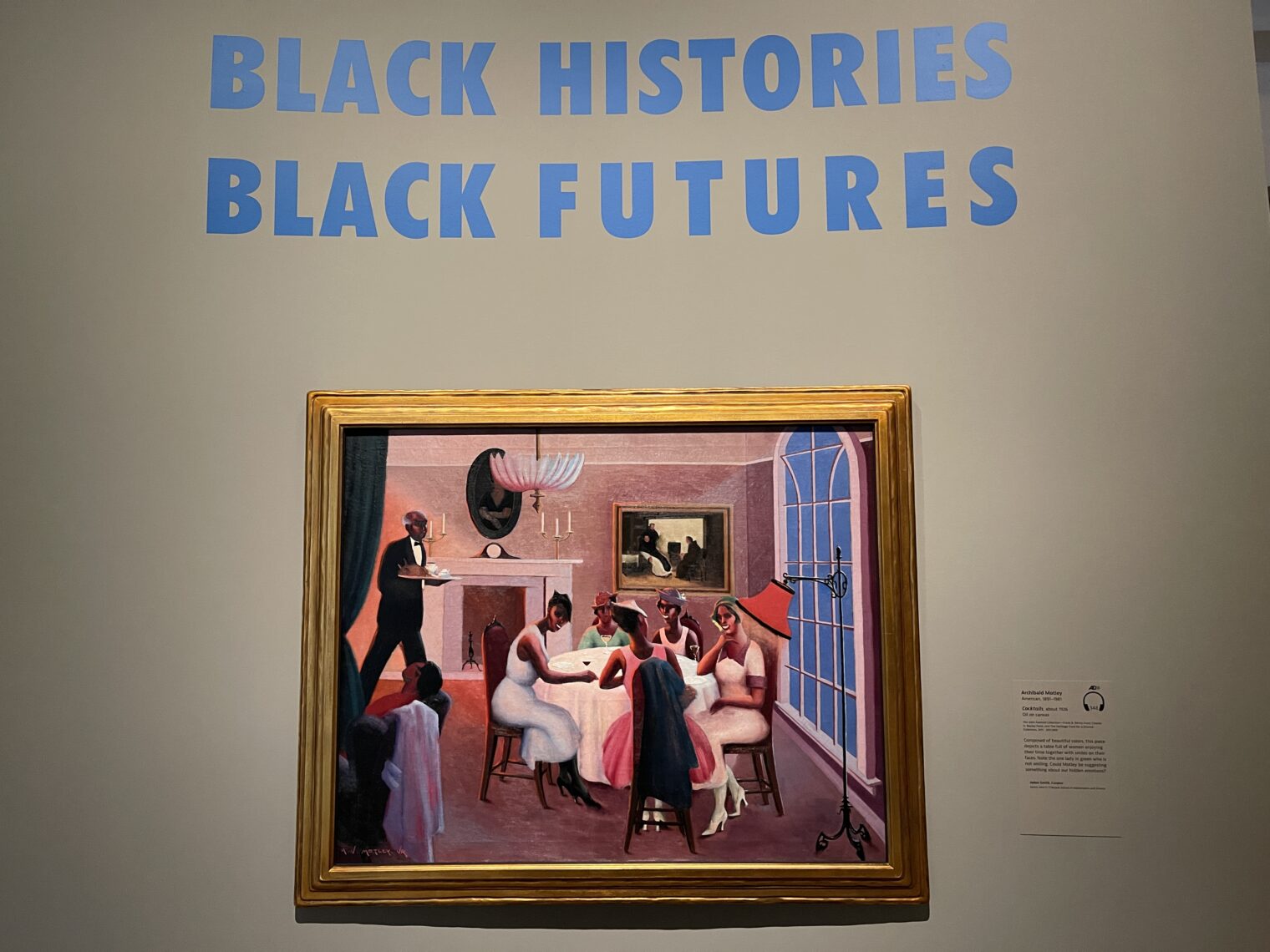

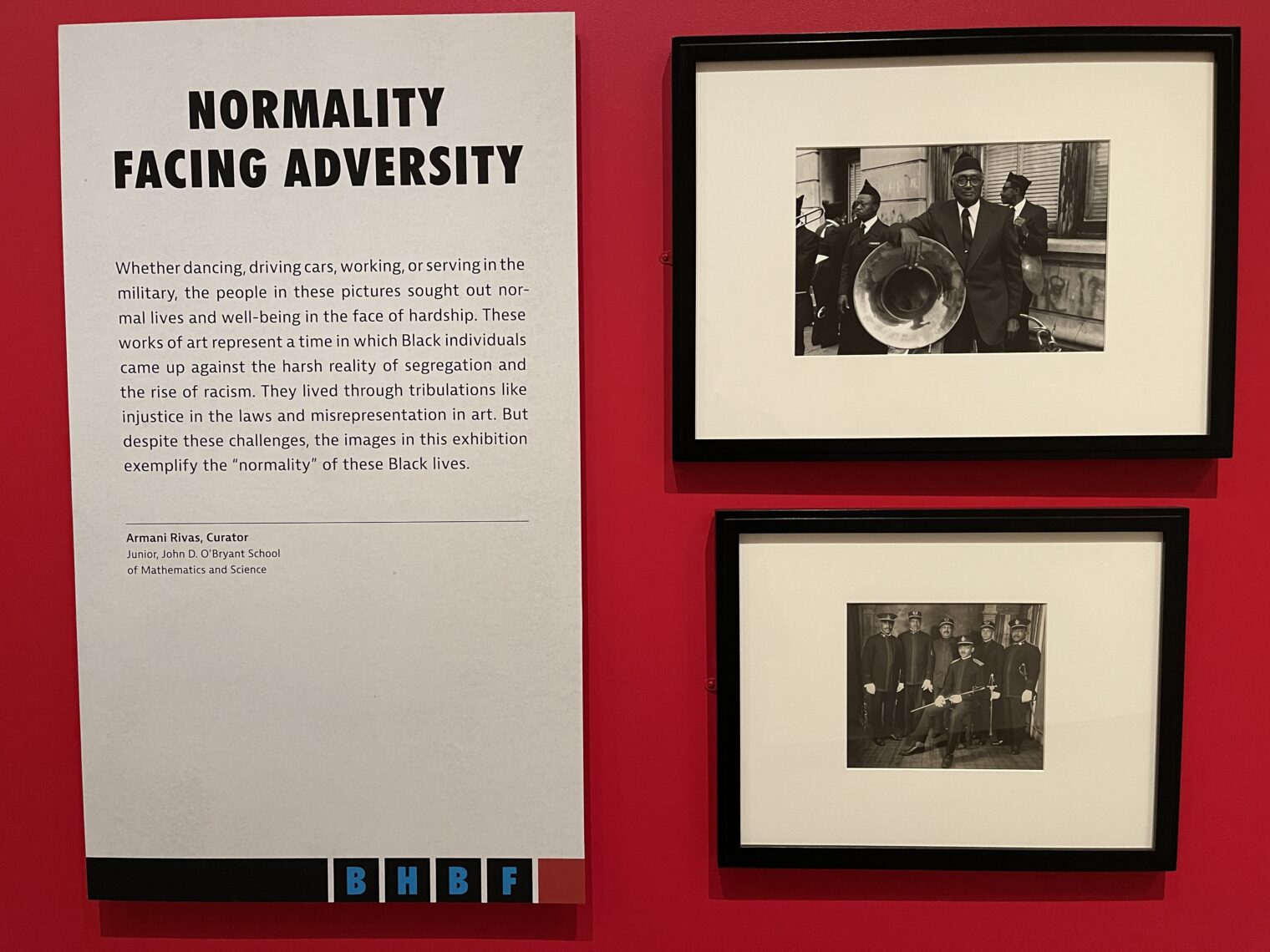

The white say-gooders who run the museum delegated curatorial responsibility to high school students (of color?):

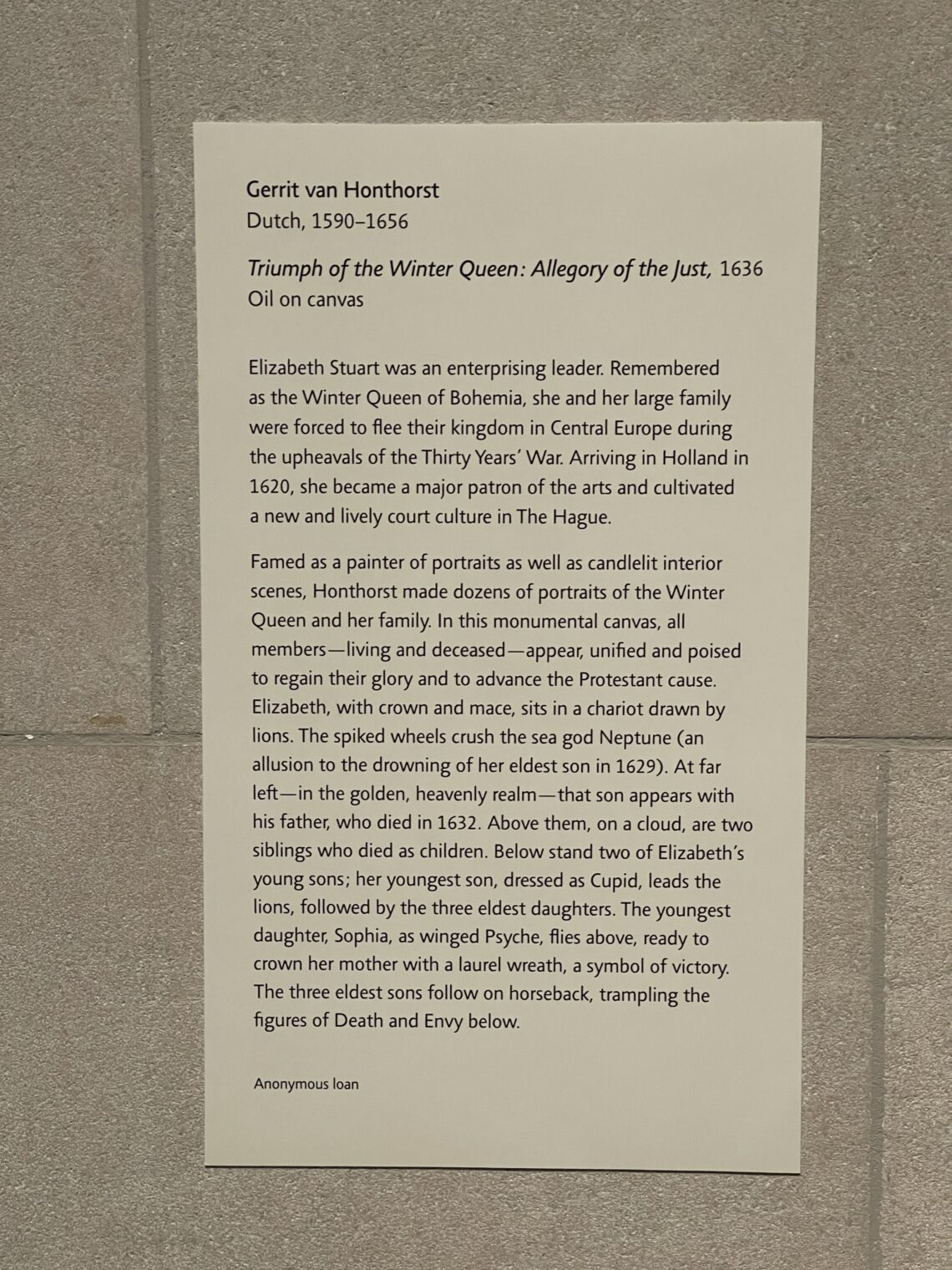

An allegory of #Science crushing coronavirus via masks and shutdown:

And let’s not forget that closing the drinking fountains will keep us all safe:

If you’re not too dehydrated from the closed drinking fountains to need to use the restroom, the good news is that the Women’s room is for those who “self-identify” as “Women”:

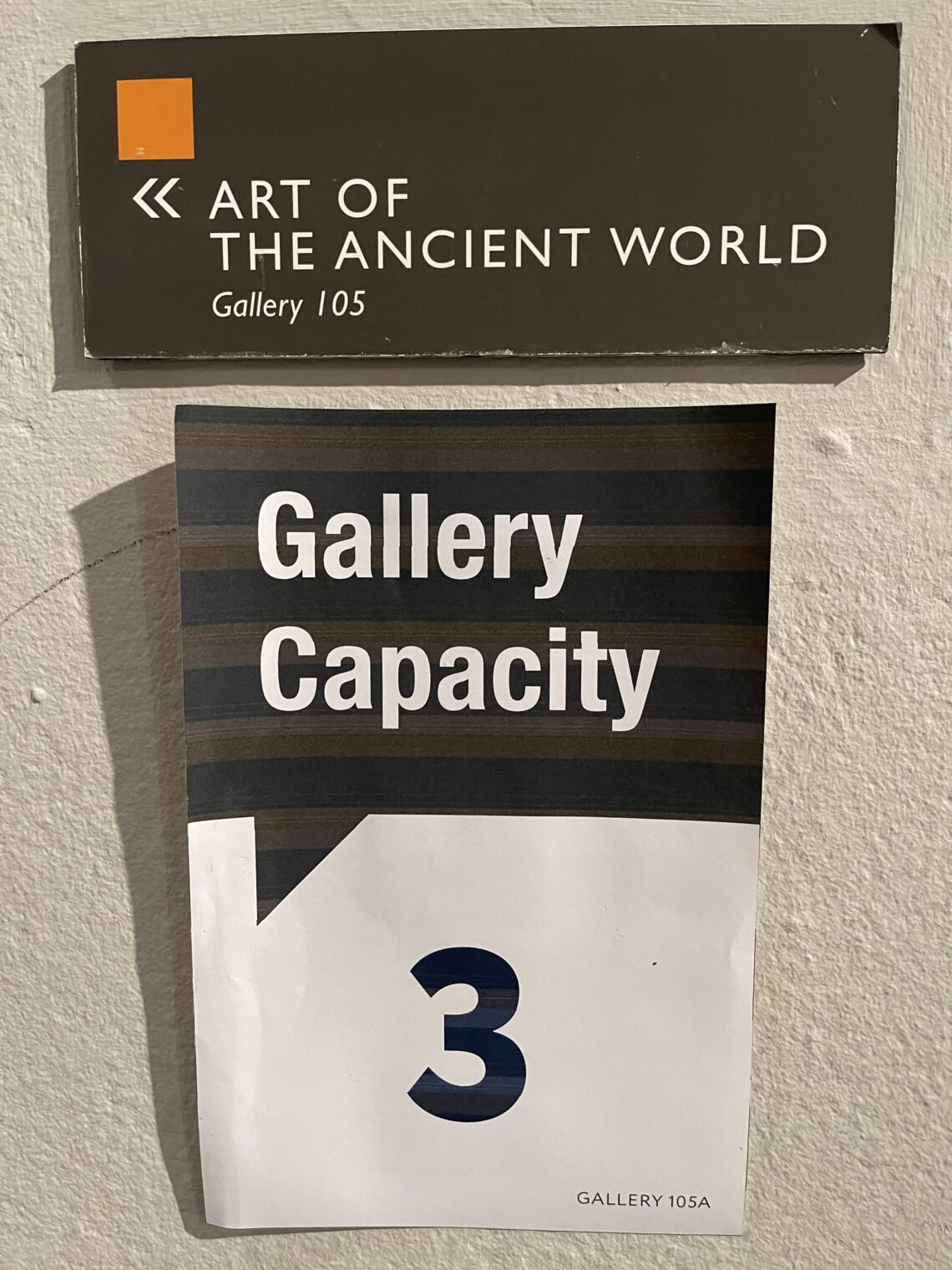

A thoughtful technocrat determined a COVID-safe capacity for each gallery in which masked (a bandana was fine as PPE) visitors might congregate:

Directional stickers on the floor would, if followed, prevent people from passing each other while moving from room to room.

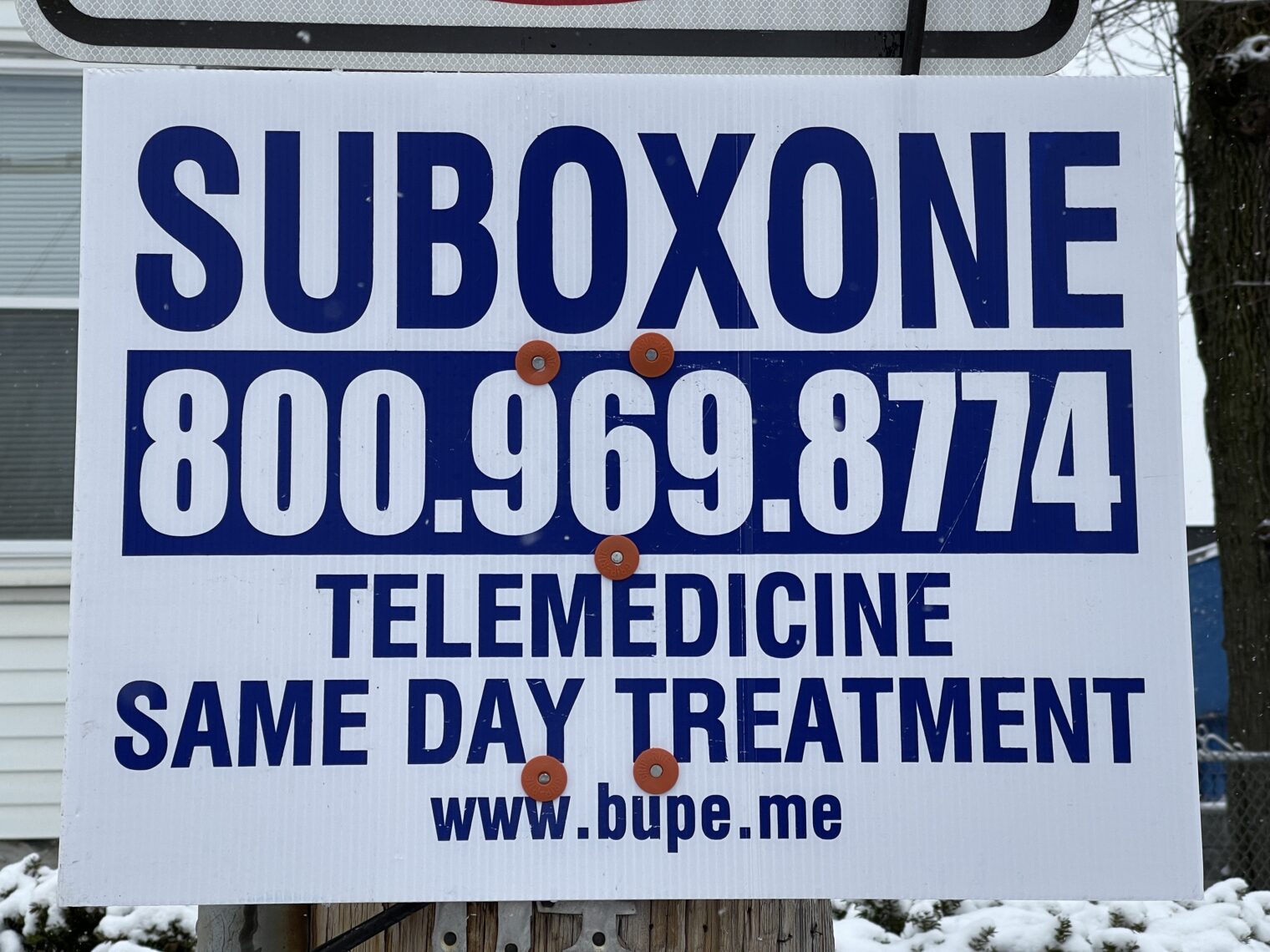

During a post-museum lunch stop, we were reminded that the same government that uses #Science to protect us all from COVID-19 will also buy us an unlimited supply of opioids as a means of treating our opioid addiction:

Although we’re members and returning to the museum would be free, we haven’t gone back. The constant COVID-19 messaging, the emptiness, and the screening procedures more elaborate than what local hospitals use for visitors made it an overly clinical experience.

Related:

- Boston Museum of Fine Arts establishes a ghetto for female artists

- Ghetto for dark-skinned snapshot subjects at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts

- Holiday fun for Bostonians: The Museum of Fine Arts Dutch show (good old days of 2015)

- The art of victimhood