“Benefit of COVID-19 vaccination accounting for potential risk compensation” (Nature, by Stanford Medical School professor John P. A. Ioannidis) points out that our current crop of COVID-19 vaccines won’t slow the spread of SARS-CoV-2 infection if humans who are vaccinated change their behavior as a result of having been vaccinated.

Tailor-made for Prof. Ioannidis: “Getting Back to Normal Is Only Possible Until You Test Positive” (The Atlantic, Alexis Madrigal). Some relevant excerpts:

I was ultracareful for 18 months. Then I got COVID.

When I first received the invitation to the wedding where I would eventually get COVID, I was on the fence about attending at all. My best friend had gone through a tough divorce and was remarrying. I was thrilled for him. His wedding had been put off repeatedly because of COVID, and this was the couple’s second try at a real ceremony. As a bonus, the wedding would take place in New Orleans, where my friend lives. I hadn’t seen him since before the pandemic. New Orleans is a miraculous place, and my favorite city to visit in America. The notion of a trip there shone out of the fog and dreariness of this whole era of history.

The downside, of course, was the risk of exposure to COVID. Sure, I’m vaccinated—two shots of Pfizer—and the wedding’s other attendees would all be vaccinated too. But breakthrough cases happen, and we’d be in New Orleans in October, a place where cases were still high and vaccination was inconsistent. One could not expect to not get exposed to COVID.

But then I reasoned both with myself and with my wife. COVID was unlikely to kill me, a vaccinated 39-year-old endurance athlete. I would be fine, and even if I gave the coronavirus to any of my family members, they too would almost certainly be fine. My wife is vaccinated, and our young children’s risk of serious illness, while not nonexistent, is very low.

Filled with a surge of love for my friends and New Orleans and a sense that, you know what, I’m ready to nose out into a new tier of risk, I booked a flight; I’d be going solo.

As the day approached, my wife and I had not run through every scenario. I still was not precisely sure how the wedding would work, COVID-wise. My friend is a doctor, and I knew the crowd would mostly be New York and California people. There would be no anti-vaxxers among the guests, and the invitation said they’d follow the local public-health protocols.

If he/she/ze/they hadn’t gotten vaccinated, he/she/ze/they never would have gotten on the packed flights nor would he/she/ze/they have attended the wedding of the righteous (“no anti-vaxxers”) at which “at least a dozen people” contracted COVID-19. I myself exhibited the identical behavior. Not being a believer in the efficacy of facerags for the general public, I avoided getting on a commercial airline flight until after getting vaccinated (and the flights that I took ended up being packed and mostly unmasked).

Separately, the rest of the Atlantic article is a great reflection of Bay Area zeitgeist:

I spent hours in an N95 mask in the Las Vegas airport and on planes before arriving in Louisiana and heading to the welcome drinks.

My kids were so happy to see me, and after my negative result came back, to hug me. Was I actually safe? No, I knew I was not. I should have quarantined. But I had stuck my wife with the kids for four days, and I wanted to get back in the mix and help. That seemed like the right thing to do.

Moms are heroic on the one hand, but on the other hand it is unreasonable to expect a mom to be able to take care of two children for four days,

On Monday, I felt fine, but I took an antigen test anyway (negative). I scheduled a PCR test for the next day. By the time my appointment arrived, I’d started to have some postnasal drip and what felt like a possibly psychosomatic tickle in my throat. Tuesday night—four days after the wedding—my PCR result came back negative, and despite having what felt like a cold, I figured I was pretty close to being in the clear.

The next day, my symptoms were about the same. I did an intense Peloton workout and it felt fine, though maybe my legs were a little slow. I wasn’t eager to test again; a negative PCR test seemed good enough. But my wife heard me cough—one of only maybe 20 coughs throughout my whole sickness—and said, “Couldn’t you take another antigen test?”

I was on the phone with a young geographer, talking about doing research at Bay Area libraries, and kind of absentmindedly did the swabbing. When I looked down a few minutes later, I had tested positive. Maybe a false positive? I immediately took another antigen test and the little pink line was practically red, it was so dark. Wrapping up the call, I packed my things quickly, texted my wife the result, walked outside with an N95 mask on, and waited for all hell to break loose.

Like my dentist friends, he/she/ze/they has a whole closet full of N95 masks! Also note the persistence in test, test, testing until positivity is achieved!

But the real worst-case scenario was everything that happened to the people around me. My kids had to come out of school and isolate with my wife. A raft of tests had to be taken by everyone I’d had even limited contact with. (I was one of at least a dozen people at the wedding who got sick.) I had been with several older people, including my mother-in-law. For my wife and children, the tests went on for days and days, each one bringing a prospective new disaster and 10 to 14 more days of life disruption or worse.

But for me, the very worst part was my children. They knew, cognitively, that I was vaccinated and unlikely to get really sick. That said, COVID-19, for them, is a terrible thing. The past year and a half of their lives has been disrupted by this virus. They take precautions every single day not to have this happen.

Even the kids know that if you’re vaccinated it is safe to party! How old are these kids?

My nonbinary 8-year-old was so mad and maybe so scared that they could barely look at me. My 5-year-old daughter proved her status as the ultimate ride-or-die kid. She brought a chair down the street so she could sit 20 feet away from me outside in her mask, as I sat on the porch in an N95.

Five and eight and they are already experts on a disease that kills 82-year-olds.

Despite his/her/zir/their vaccine, the 39-year-old author gets about as sick as the sickest unvaccinated New Yorkers and Europeans whom I talked to back in spring 2020:

I felt pretty sick, like when you have a cold, but I’ve probably been sicker 15 times as an adult.

In other words, a bad cold/flu. The kicker, though, is that he/she/ze/they imagines that he/she/ze/they would have died without the sacrament of vaccination:

These vaccines are amazing. I was and am fine. [emphasis in original]

I understand that my scenario is far better than could or would have played out in a pre-vaccination world.

What about the people infected with SARS-CoV-2 in 2020, pre-vaccines, who never had any symptoms at all? (81 percent of cruise ship passengers who tested positive, for example; or at least one third, if you believe the other side of the #Science coin) They were and are fine. If the 39-year-old endurance athlete author was seriously ill despite vaccination, shouldn’t he/she/ze/they actually suspect that his/her/zir/their vaccine was, at best, laughed at and ignored by the virus?

Readers: I hope that you enjoy the Thanksgiving flights and gatherings that you probably wouldn’t have risked if you hadn’t been vaccinated!

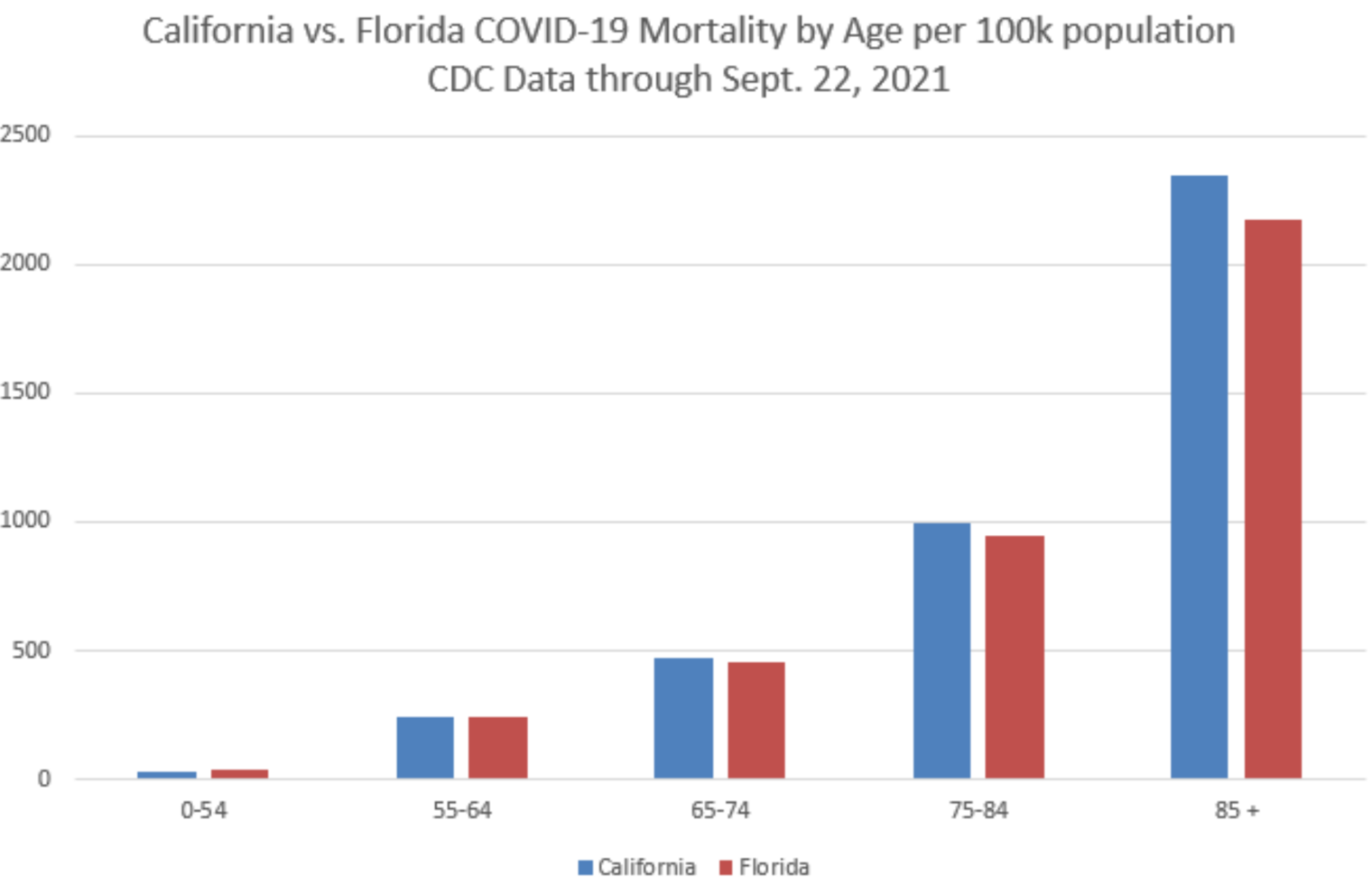

Practical Take-aways: (1) Don’t get more COVID-19 tests than you have to! With current test tech, regardless of what’s in your body, you will eventually test positive; (2) if you don’t want to get COVID-19, stay home (or move to Florida, currently the nation’s lowest-risk state, and stay outdoors!).

Recent group chat exchange:

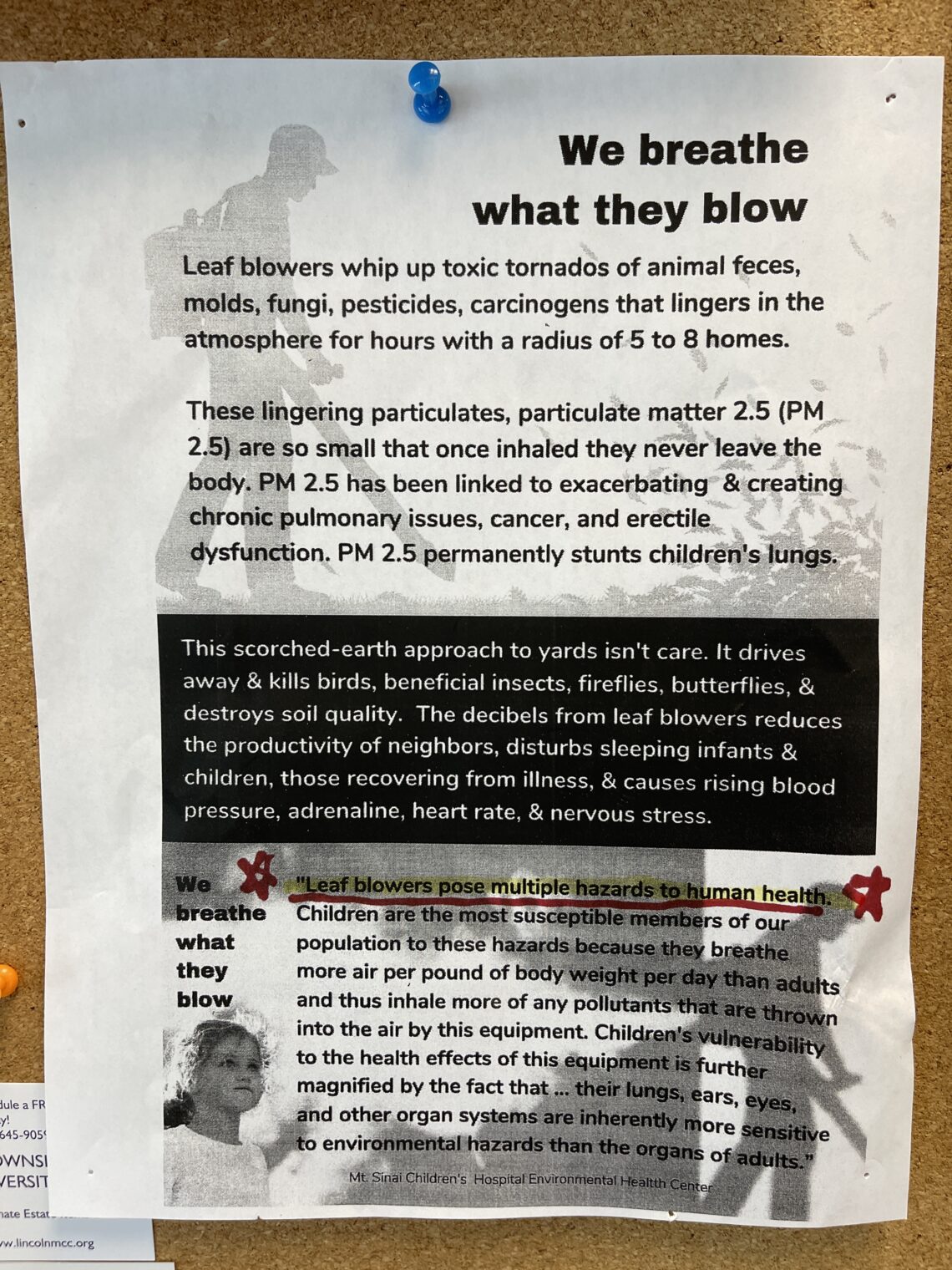

- friend 1: So i am in Poland and i got the f***ing flu. Have been coughing for 10 days. Question: Since everyone is in masks, how do I get the flu if masks work?

- me: 10 days might just be cold, not flu

- friend 1: And i didn’t have sex with any polish prostitutes

- friend 2: YET

- friend 1: Ok and cold is unaffected by masks? What is the science on that?

- me: I think those who #FollowScience are ready for you! Coronavirus is spread by airborne particles, which is why we #MaskUpAndStopTheSpread On the other hand, every other disease is spread by surface contact, which is why kids still have colds

- friend 1: I am so damn sick of all of it. Germany is on the rise despite compliance and FFP2 masks everywhere

Related:

Full post, including comments