From The Accidental President: Harry S. Truman and the Four Months That Changed the World (A.J. Baime)

General H. H. “Hap” Arnold, head of the army air forces, had gambled $3 billion—and his entire career—on the development of the B-29 Superfortress. (The B-29 program cost taxpayers considerably more than the Manhattan Project did.)

The first incendiary mission was flown March 9–10, using bombs loaded with white phosphorus and napalm; the latter substance was a new highly flammable fuel gel developed in a Harvard laboratory. The B-29 crews had been instructed on the best way to drop their payloads, to create the maximum amount of fire: “The bombs from a single ship must be spaced so as to assure a merging of the fires started by each bomb into a general conflagration before fire fighters have had time to put them out . . . With a full bomb load . . . of M-69 incendiaries, the area burned out by a single ship should be around 16 acres.”

That first firebombing of Tokyo resulted in the largest death toll of any air raid, in any war ever, up to that point—an estimated 100,000 Japanese, likely more. Civilians hiding in dug-out holes that served as crude bomb shelters were baked alive by the towering flames, the heat reaching 1,800 degrees F. Others took refuge in canals only to be boiled to death in the searing heat.

On August 1, Curtis LeMay issued a warning to Japanese citizens in twelve cities to leave their homes and jobs to save their lives, as their cities were top on what was being called in the press LeMay’s “death list”—Mito, Fukuyama, Ōtsu, among others. On August 2, the day Truman met with the king of England and then started the transatlantic journey home aboard the Augusta, the Twenty-First Bomber Command struck the enemy with what the New York Times called “the greatest single aerial strike in world history.” Nearly 900 B-29s pounded targets with 6,632 tons of conventional and incendiary bombs. The flames engulfed miles of Japanese cities. “The sight was incredible beyond description,” recalled one B-29 crewman. These attacking planes saw no opposition. “They knew we were coming but they didn’t do anything about it,” said one officer.

How did folks on the home front feel about this?

No outrage came from the American public. All the critics who had hurled calumny at the British for their willingness to bomb civilian population centers in Nazi Germany now remained silent. In fact, popular American opinion now seemed to embrace this form of warfare. Newspaper articles ran long columns with pictures of the factories where the firebombs were built. FILLING “GOOP BOMBS” THAT ARE FRYING JAPAN LIKE MIXING CAKE DOUGH, stated a Boston Daily Globe headline. “The M-69s [firebombs] become miniature flamethrowers,” reported Time magazine, “that hurl cheesecloth socks full of furiously flaming goo [napalm] for 100 yards. Anything these socks hit is enveloped by clinging, fiery pancakes.” Only Secretary of War Stimson urged an end to the indiscriminate killing. Stimson went to see the president. “I told him I was anxious about this feature of the war for two reasons,” Stimson wrote in his diary. “First, because I did not want to have the United States get the reputation of outdoing Hitler in atrocities; and second, I was a little fearful that before we could get ready the Air Force might have Japan so thoroughly bombed out that the new weapon would not have a fair background to show its strength.”

Obliquely threatened with the atomic bomb prior to its use, the Japanese refused to surrender:

On the same day the Senate ratified the UN Charter, Japan responded officially to the Potsdam Declaration. Tokyo was rejecting it. The Japanese government “does not consider [the Potsdam Declaration] of great importance,” Prime Minister Kantarō Suzuki said in a press conference. “We must mokusatsu it.” When the Foreign Broadcast Intelligence Service translated the word mokusatsu, it used the word ignore. In reality, the word meant “to kill with silence”—a vague notion. Another report from a Japanese news agency quoted the Japanese reaction to the ultimatum, saying Japan would “prosecute the war of Great East Asia to the bitter end.”

Of course, Japan did surrender after the atomic bombs were dropped, despite the fact that these bombings were less destructive to life and property than the firebombings had been.

I wonder if this is analogous to the coronaplague situation. Losing millions to influenza over the years never bothered us. Losing millions to automobile accidents that would be easy to prevent with lockdown-style regulations (e.g., only “essential” trips are authorized and private car ownership/amateur driving are banned) has never bothered us. Losing Americans to diabetes, heart disease, and other inevitable side effects of obesity doesn’t bother us enough to outlaw restaurants serving 2,000-calorie meals (or make us think twice about locking people into sedentary habits for 3 months). Losing Americans to cancer didn’t bother us enough to refrain from shutting down ultrasound and other cancer screenings from March through June 2020.

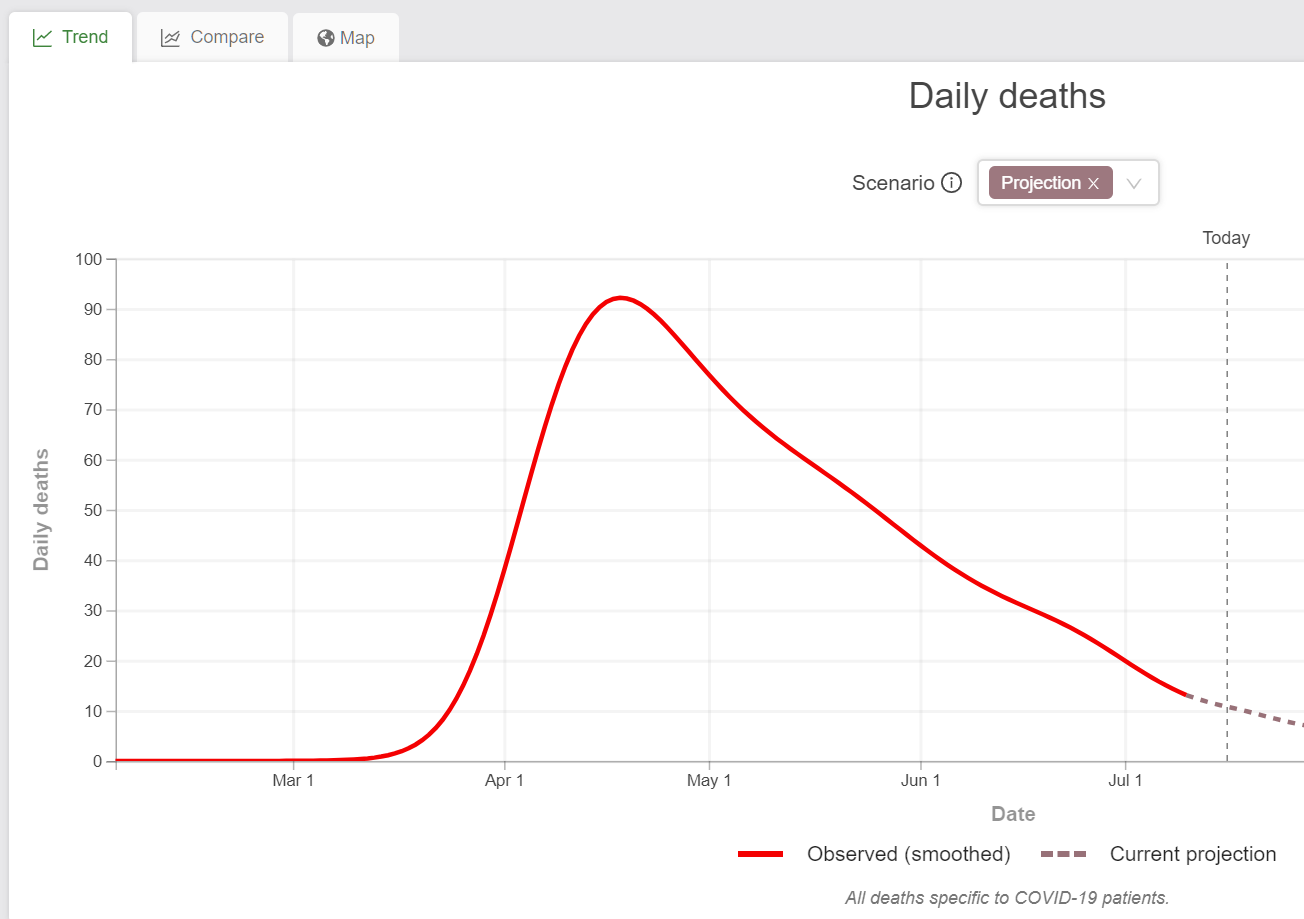

Unmitigated coronaplagues are sharp and painful, however. Even with a “do almost nothing” approach like Sweden took, the total number of deaths is smaller than causes of death that don’t motivate us to change behavior or policy. But the deaths are concentrated over a two-month period rather than being spread out over a year or two. From IHME:

Readers: What do you think? Correct SAT answer? “Atomic bomb is to firebombs as coronaplague is to influenza”

Bonus, from my Japan photos, Kyoto (spared both firebombs and the atomic bomb):

Related:

Full post, including comments