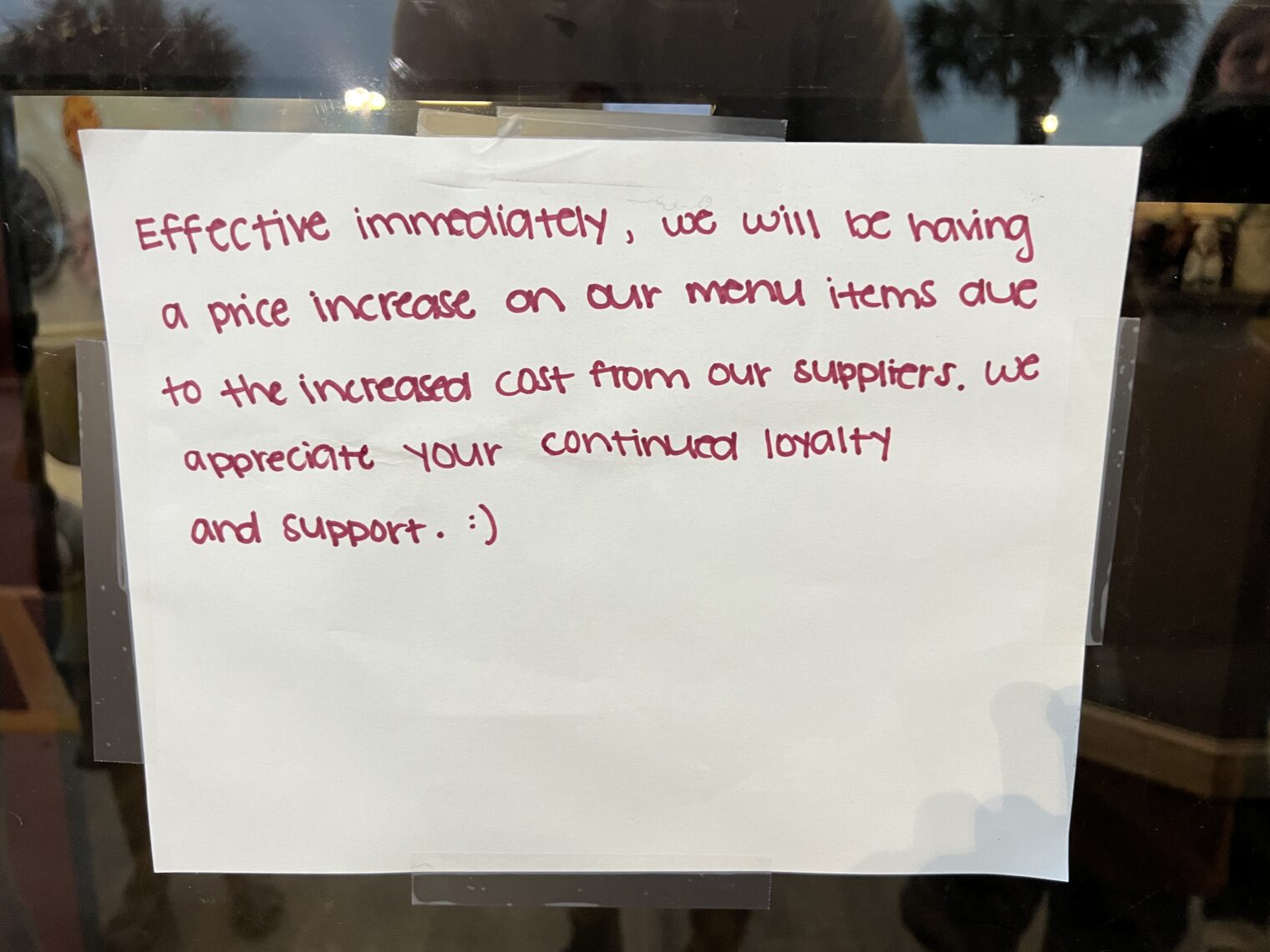

“Renters across US face sharp increases – averaging up to 40% in some cities” (The Guardian):

According to an analysis conducted by RedFin, rents in the US jumped 14% in December 2021 to $1,877 a month, the largest rise in more than two years.

Some of the most affected cities included Austin, Texas, with a 40% increase in rental prices compared with a year previous, New York City at a 35% increase, and several metro areas in Florida exceeding over 30% increases in rental prices.

Members of the 2SLGBTQQIA+ community are the worst-afflicted, according to The Guardian:

His $1,500-a-month rent was already a struggle for him to pay, and if late on rent payments he incurs a $100 fee. With the latest rental increase of nearly $450, he worries about his future in Sarasota, a community he’s lived in and helped build as a promoter and organizer for LGBTQ events over the years.

“Now, I can’t even afford to live in the community that I helped to create,” added Beadle. “This is not OK, There needs to be an answer for the young, single people who are trying to survive and thrive. We can’t just be happy with being able to pay rent one more month not knowing if we will have a place to live next month.”

One week before his wedding in January 2022, Joey Texeira and his partner received a lease renewal from their landlord in New York City, with a 30% increase to rent of $750 a month for a one-year lease renewal or a 41% rent increase of $1,050 a month for a two-year lease renewal for an apartment they have lived in since December 2020. The lease renewal would start on 1 May.

“We’re very stressed and don’t know exactly what we plan to do yet,” said Texeira.

His husband was also unexpectedly laid off recently and their neighbors downstairs were recently priced out of the apartment building with a rental increase of $250 to $500 added to their monthly rent.

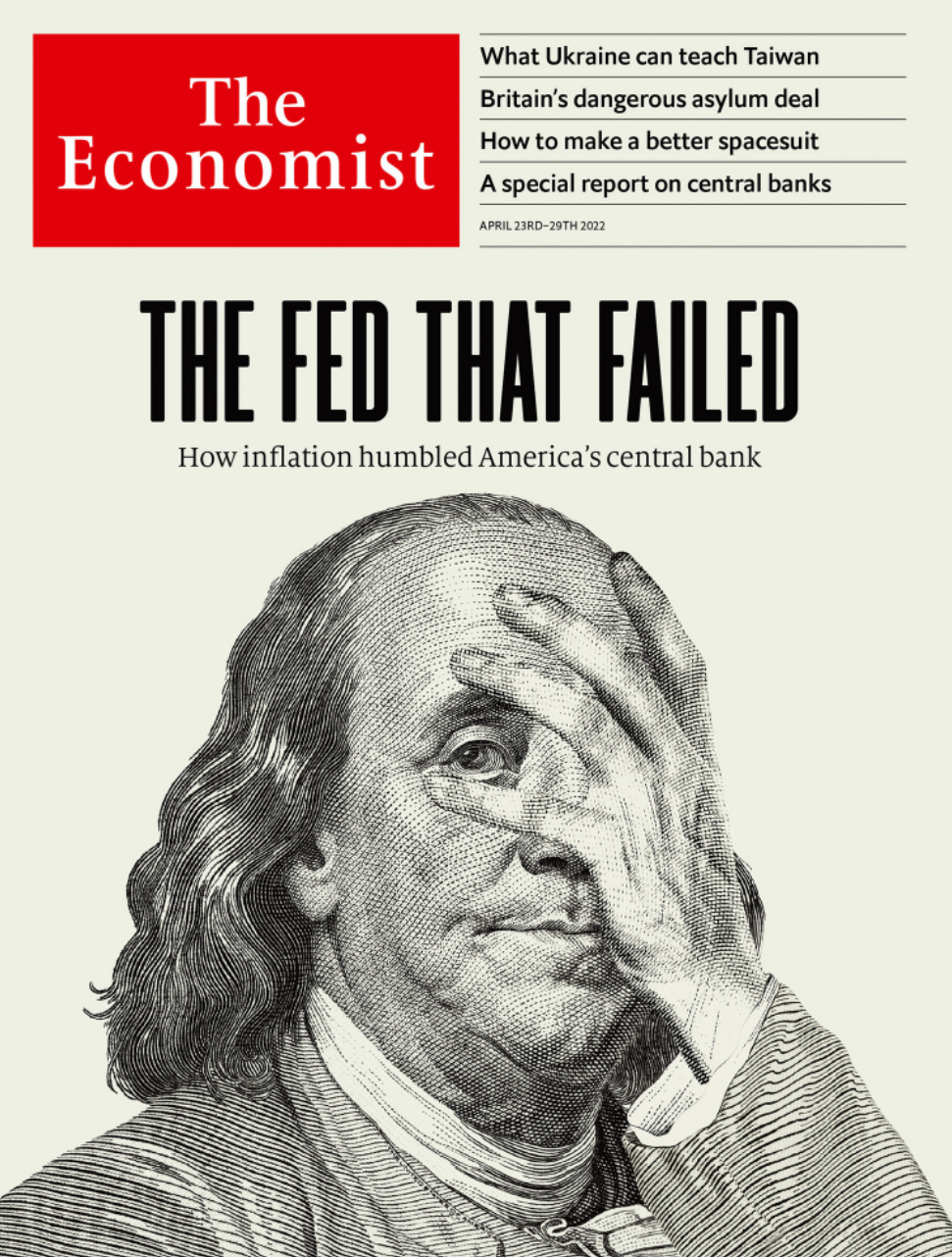

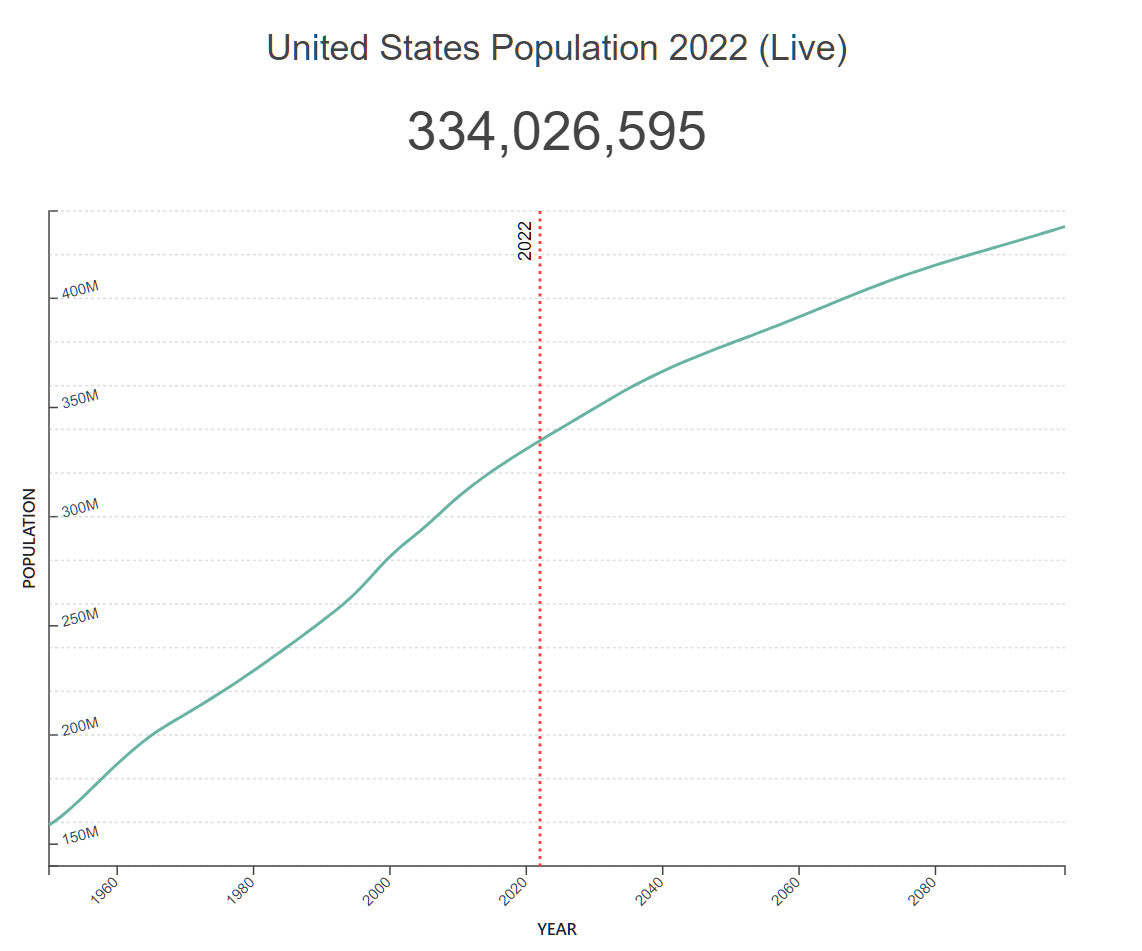

How is it possible that the market-clearing price for housing is going up? Let’s look at the demand curve:

Why does the demand curve rise? Partly this is due to the no-fault (“unilateral”) divorce revolution, which creates more households per capita (the typical U.S. state’s family law takes people out of the workforce (successful plaintiffs face a huge disincentive to work because W-2 wages might result in a reduction of the family court gravy train), which reduces GDP available to build housing). But mostly the demand growth is due to immigration: “Modern Immigration Wave Brings 59 Million to U.S., Driving Population Growth and Change Through 2065” (Pew 2015).

A larger population might not result in a housing crisis if every new addition to the population had sufficient skills to earn enough to afford a new house, but even Americans at the median cannot afford to live in a new apartment (see City rebuilding costs from the Halifax explosion for some numbers).

Leading up to the shock and horror of the 40 percent rent increase story, The Guardian has been advocating for increased low-skill immigration to the U.S. Here’s an example explicitly calling for “open borders” … “Why Democrats should support open borders” (Reece Jones, February 2018):

… the Republican leadership has already settled on an extreme position that will substantially reduce all immigration to the United States. … In the face of this recalcitrance, the Democrats must rethink their current incoherent immigration policy and argue robustly for more open borders.

Open borders could have an enormous positive impact on GDP worldwide.

The concern that some citizens might lose jobs to immigrants is not supported by research. One study found migrant and native workers are employed in different sectors of the economy, another showed that migrants create 1.2 additional jobs beyond the job they do because they rent an apartment, buy a car, and frequent local businesses.

How many people would actually move if borders were open? A 2011 Gallop survey found that 14% of the world population would like to move to another country, with perhaps 100 million wanting to go to the US. These numbers may alarm some, but these movements would happen over years, or even decades.

… there is not a moral or ethical reason to justify restricting the movement of other human beings at borders.

I disagree with Professor Jones that there are only 100 million people who would want to come to the world’s 2nd most generous welfare state (measured by percentage of GDP devoted to welfare). The U.S. offers free unlimited health care via Medicaid and/or simply going into a hospital for “charity care.” Why wouldn’t anyone on Planet Earth who has a serious illness want to come to the U.S. for pull-out-all-the-stops treatment? The cruel National Health Service in the UK won’t spend money if the bureaucrats don’t think it is worth it (explanation). But if you’re 80 years old and think that you might benefit from some joint replacements, why not pop over from the UK to the US and get the $300,000 of surgery that the UK’s NHS is denying? Since the borders are open, it will always be possible to migrate back.

On the other hand, I agree with Professor Jones that, under the ethics and morality professed by a majority of Americans, there is no reason to deny people from the world’s poorest countries free housing, health care, food, and smartphone here in the U.S. If “housing is a human right” is our reason for providing taxpayer-funded housing to an American who chooses not to work, an undocumented migrant should be equally entitled to a free house since the migrant is equally human.

Maybe that “open borders” headline is an outlier? Let’s sample “opinion plus US immigration” in The Guardian. “The Biden administration has ended use of the phrase ‘illegal alien’. It’s about time” (Moustafa Bayoumi, April 2021):

Real immigration reform must follow. Paths to citizenship for the millions of undocumented people who are living in the shadows must be made into law. Unaccompanied minors must be afforded the same levels of safety and dignity we would want for our own children. And asylees must be admitted at far higher numbers than currently permitted.

Every asylum-seeker needs a place to live, presumably. And someone who claims to be an unaccompanied minor (there is no way to verify the age of an “undocumented” person since one cannot ask for his/her/zir/their passport) can’t have a safe and dignified lifestyle without a taxpayer-funded apartment.

“Calls to end inhumane border conditions aren’t enough. Ice must be abolished” (Natascha Elena Uhlmann, September 2019):

… where are we as a society if we cannot dream bigger? What does it mean that some of our most beloved writers – who have laboriously envisioned new and radical worlds – didn’t imagine a future that respects the right to human movement?

It is by refusing to concede to a rightwing vision of possibility that unimaginable prospects become reality.

With our imagination we can turn currently vacant land into 7 million houses/apartments for “extremely low-income renter households” (the “gap” as of March 2021).

“‘Australia’s loss is America’s gain’: the Nauru and Manus refugees starting anew in the US” (Anne Richard, January 2019):

Australia had stopped thousands of asylum seekers from reaching its shores and had arranged to detain them on islands in the South Pacific; the US had agreed to resettle some in America. … As the assistant secretary of state for population, refugees and migration in the US, I had signed the deal in September 2016. Had our team said no to the Australians, it might have kept the pressure on them to change their policy, but reports about the dire conditions on the islands worried us and my sense was the refugees would be better off restarting their lives elsewhere as soon as possible.

I met Sri Lankan parents of three children – including a baby born under difficult circumstances in the Pacific Island nation of Nauru – who are now living on the US west coast, happy that their children will receive an education, have a good future and experience freedom. The father, however, fears the earnings from his job at an Indian restaurant will not be sufficient to pay the rent for a two-bedroom apartment and other bills.

… three young men told me they had fled their village in Pakistan … One is working the graveyard shift at a convenience store and another, who had earlier studied medicine, is now a landscaper.

(Would the profiled 2SLGBTQQIA+ folks afflicted with 30-40 percent rent increases have preferred to pay their old rent and pulled a few weeds themselves and perhaps waited until 7 am for the convenience store to reopen?)

“Ice is a tool of illegality. It must be abolished” (Zephyr Teachout, June 2018):

On Sunday, Trump doubled down and took direct aim at our constitutional order when he tweeted: “When somebody comes in, we must immediately, with no Judges or Court Cases, bring them back from where they came. Our system is a mockery to good immigration policy and Law and Order.”

This is a direct affront to the most foundational principles of public morality and law. Our constitution insists that “no person shall be … deprived of life, liberty or property, without due process of law”. It should not need saying, but undocumented immigrants are persons.

“Why Trump thinks domestic violence victims don’t deserve asylum” (Jill Filipovic, June 2018):

What else, other than out-and-out hostility and a desire to hurt the most vulnerable, justifies Sessions’s decision to remove asylum protections from women suffering violence at the hands of their partners?

In other words, anyone willing to spin a tale of domestic suffering, which cannot possibly be verified from 1,000+ miles away, is entitled to live in the U.S. forever.

Going back to the happy days before the Trump dictatorship… “Bernie Sanders is wrong on open borders: they’d help boost the economy” (Cory Massimino, August 2015):

Bernie Sanders has come out against open borders, claiming they are a “right-wing proposal” that “would make everyone in America poorer.” He argues that, while we have a “moral responsibility” to “work with the rest of the industrialized world to address the problems of international poverty… you don’t do that by making people in this country even poorer.”

In other words, Bernie predicted, 6 years in advance, that non-immigrant Americans would become poor via rent increases! And some of the haters who comment here say that Comrade Bernie does not understand economics!

Related:

Full post, including comments