Rudy Giuliani would still be rich if he’d moved to Florida, bought a house and universal life insurance, and created a Nevada trust

Happy National Florida Day, celebrated every year on January 25 to commemorate the founding of Florida becoming a state on… March 3, 1845. (CBS makes no attempt to explain the apparent discrepancy.) Let’s check in with someone who should have paid more attention to National Florida Day…

“Giuliani, Slow to Give Up His Belongings, Tests Patience of Court” (New York Times, January 3, 2025):

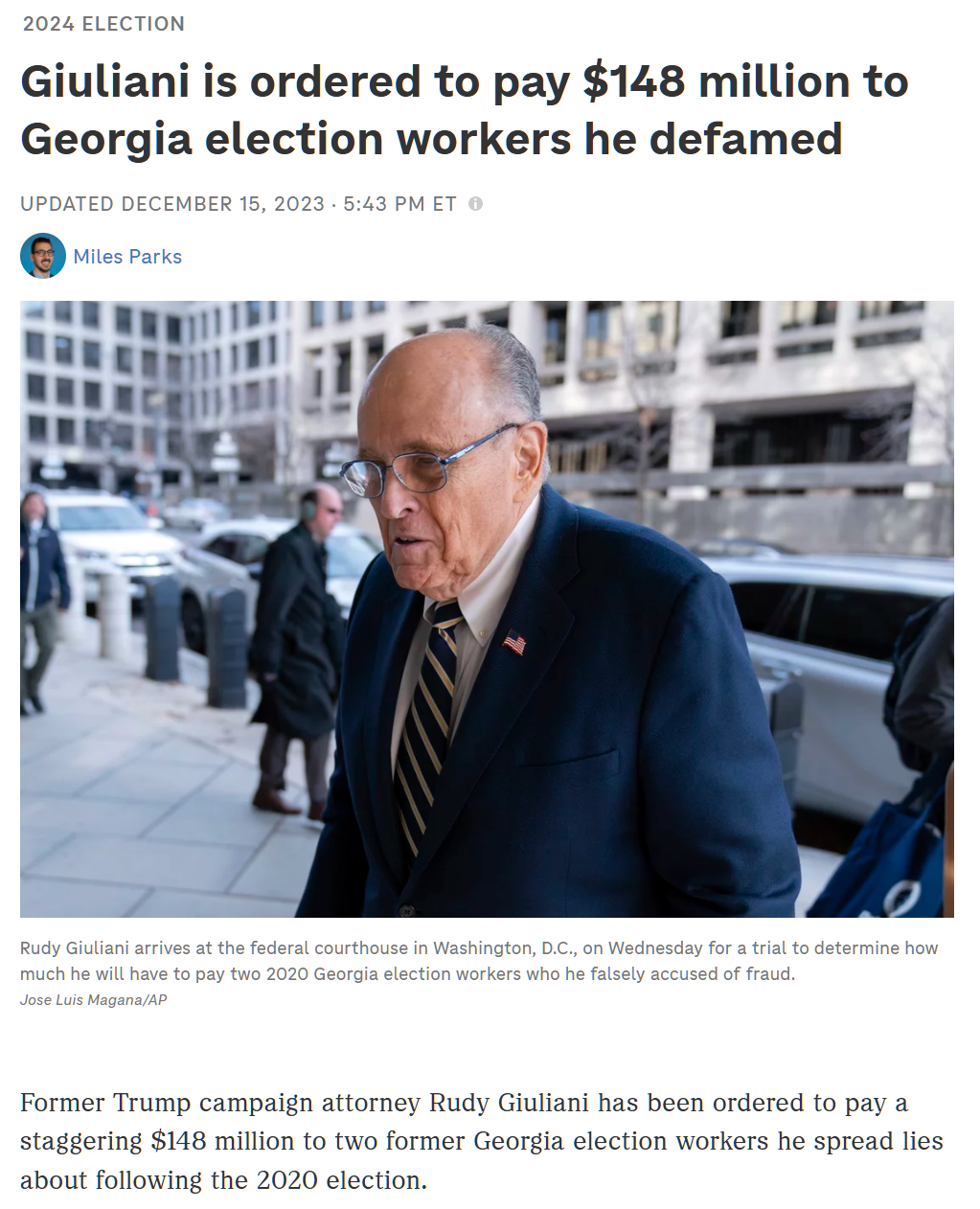

After several missed deadlines and extensions, Rudolph W. Giuliani, the former mayor of New York, could be found in contempt of court on Friday for failing to deliver assets worth $11 million to two poll workers he defamed after the 2020 presidential election.

If he is held in contempt, he could face steep penalties, including jail time.

Mr. Giuliani, 80, was set to appear in federal court in Lower Manhattan to justify the stalled handover of some of his most prized possessions, including a penthouse apartment in Manhattan, a collection of Yankees memorabilia, luxury watches and a vintage Mercedes-Benz convertible. (It is unclear whether Mr. Giuliani will appear in person; his lawyers have indicated that he might attend the hearing remotely, citing health problems.)

The transfer was originally scheduled to take place in October, as a down payment on a $148 million judgment that he was ordered to pay to two Georgia election workers, Ruby Freeman and her daughter, Shaye Moss. Mr. Giuliani had claimed, without evidence, that the women had helped steal the presidential election from Donald J. Trump more than four years ago.

After a lifetime of work, the guy was on track to be destitute, with all of the money that he earned going to a couple of election workers in Georgia whom nobody had ever heard of and who nobody today has apparently heard of (the NYT didn’t think it worth mentioning their names). His two children (Wikipedia) were on track to inherit nothing (though maybe indirectly they would because their mom was divorced from their father in 2001).

Giuliani tried to salvage about $3 million in home equity via a foxhole conversion to Floridianism on July 15, 2024 (a primary residence in Florida cannot be acquired by a creditor). Perhaps this was a factor in a settlement (NYT, Jan 16) where he managed to cling to at least some portion of his former wealth.

What could Giuliani have done as soon as he got sued? Or, indeed, at any time during the trial that wiped him out?

- sold all real estate outside of Florida

- consolidated all real estate equity into a single no-mortgage primary residence (“homestead”) in Florida (he likes Palm Beach and his maximum estimated net worth was $50 million so he could have easily found a single house to absorb all of his real estate wealth)

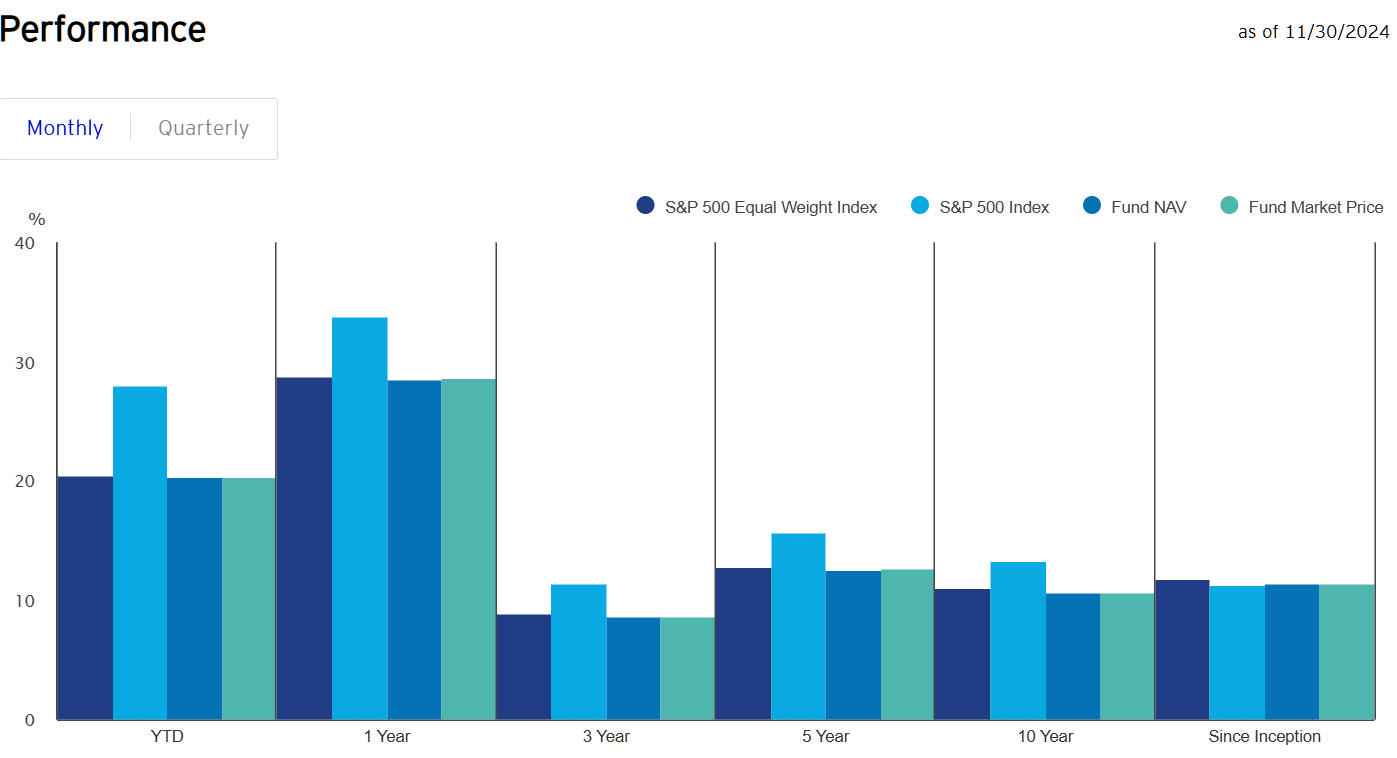

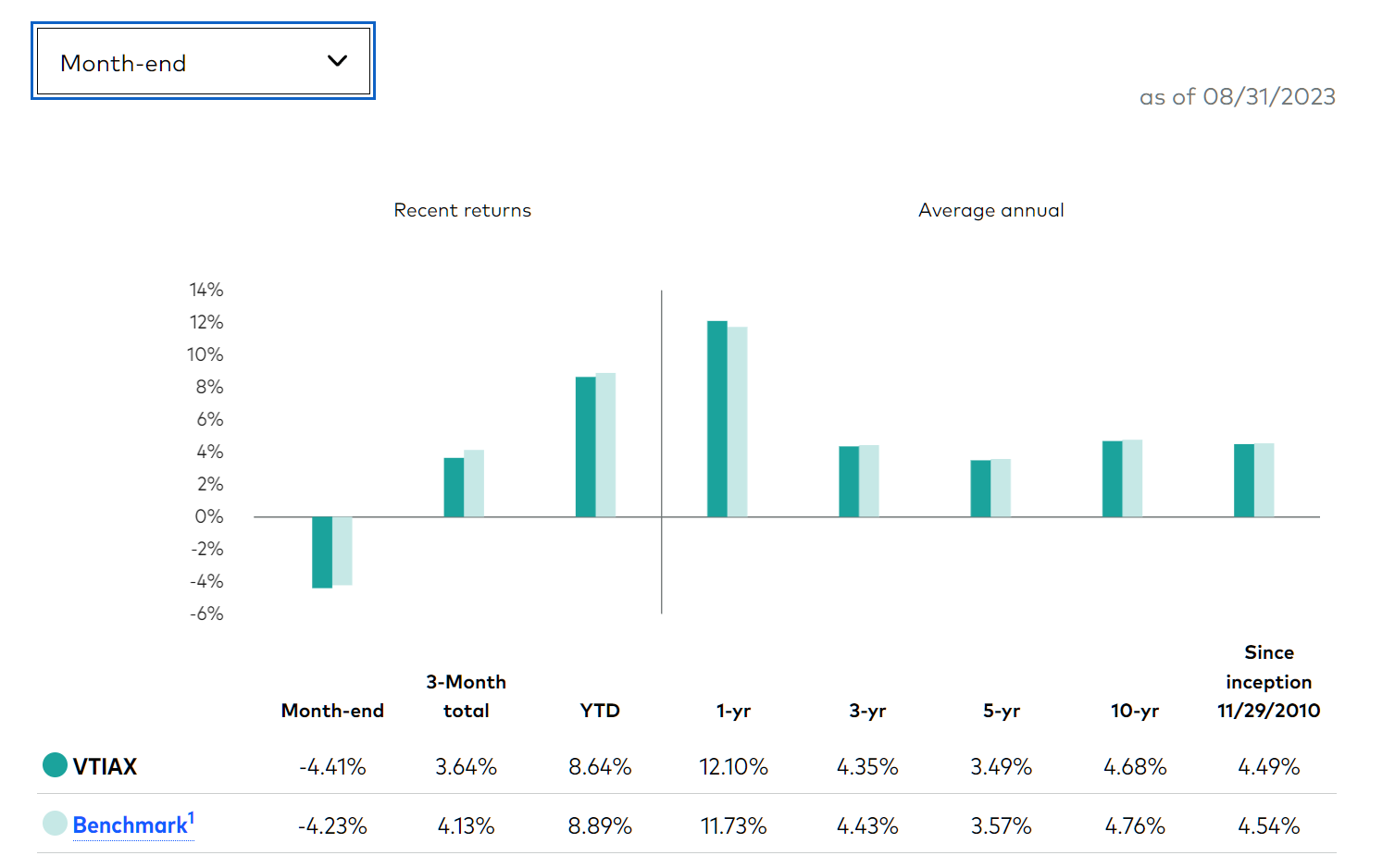

- sold all financial assets and personal property and split the proceeds into a life insurance policy for himself and a Nevada trust for his heirs

(A universal life policy can be tapped into while the insured is still alive and it can function essentially like a high-fee mutual fund account that has the advantage of no taxation of dividends and no taxation of capital gains when it finally pays out (the capital gains exemption is of more value when the insurance policy is held by an irrevocable trust; any investment positions held personally and not sold during a person’s lifetime will “step up” in basis on death anyway).

Florida State Constitution (which also prevents a state personal income tax from being dreamed up by a righteous legislature), Article X, Section 4:

(a) There shall be exempt from forced sale under process of any court, and no judgment, decree or execution shall be a lien thereon, except for the payment of taxes and assessments thereon, obligations contracted for the purchase, improvement or repair thereof, or obligations contracted for house, field or other labor performed on the realty, the following property owned by a natural person:

A relevant statute:

222.14 Exemption of cash surrender value of life insurance policies and annuity contracts from legal process.—The cash surrender values of life insurance policies issued upon the lives of citizens or residents of the state and the proceeds of annuity contracts issued to citizens or residents of the state, upon whatever form, shall not in any case be liable to attachment, garnishment or legal process in favor of any creditor of the person whose life is so insured or of any creditor of the person who is the beneficiary of such annuity contract, unless the insurance policy or annuity contract was effected for the benefit of such creditor.

(222.21, “Exemption of pension money and certain tax-exempt funds or accounts from legal processes”, may also be relevant)

Why a Nevada trust? Steve Oshins explains it better than I can in a lot of scenarios. Florida appears to offer many of the advantages of Nevada for a conventional trust (not a “domestic asset protection trust” that is “self-settled” (the grantor is also the beneficiary)), but it favors beneficiaries to the point that litigation becomes much more likely than with a Nevada, New Hampshire, or South Dakota trust. A beneficiary can sue because he/she/ze/they is unhappy about a trustee’s decision, e.g., to pay some other more virtuous beneficiary more, and not run afoul of a “no contest” clause. Nevada, as well as some other states, are more likely to consider the grantor’s intent as primary. All of that said, a Florida trust for his kids should have been protected from his plaintiffs.

It is kind of surprising to see such poor planning from a person who is a lawyer and who has been surrounded by lawyers. If the jury verdict had gone the other way, Giuliani wouldn’t have given up anything other than some commissions and the right to continue paying New York State and New York City income taxes. The cobbler’s children have no shoes?

So… let’s remember on National Florida Day that Florida is a place where a person can keep much or most of what he/she/ze/they has earned even if positioned for insolvency in the typical state. (One type of predator against whom Florida law is useless: a divorce, alimony, or child support plaintiff! In those situations, having a Nevada DAPT and actually living in Nevada is the solution.)

Background, from state-sponsored NPR:

From state-sponsored PBS, Giuliani can’t use the bankruptcy process to retain enough for a meager personal lifestyle:

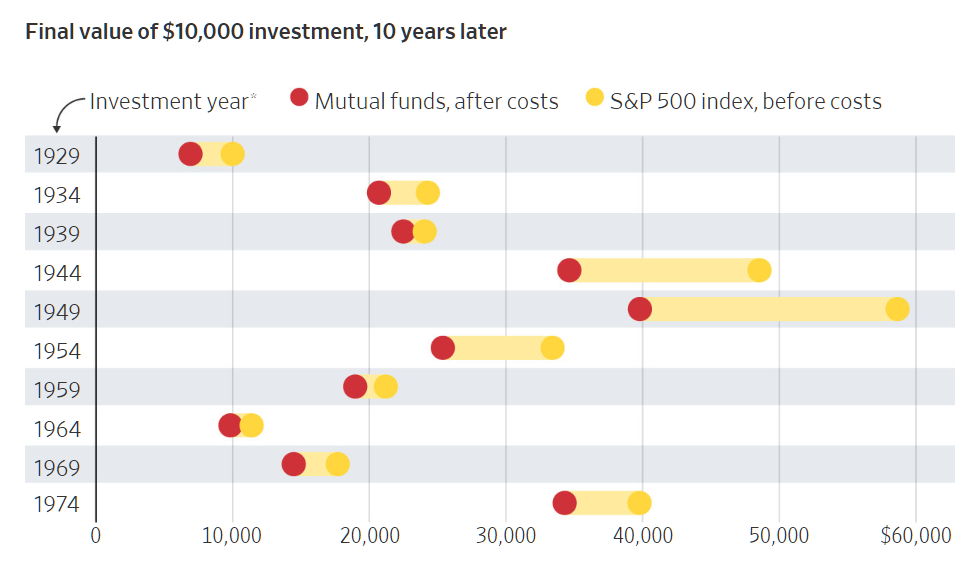

Full post, including commentsWhen Giuliani filed for bankruptcy, he listed nearly $153 million in existing or potential debts. That included nearly $1 million in state and federal tax liabilities, money he owes lawyers and millions more in potential judgements in lawsuits against him. He estimated at the time he had assets worth $1 million to $10 million.

In his most recent financial filing in the bankruptcy case, he said he had about $94,000 in cash at the end of May and his company, Guiliani Communications, had about $237,000 in the bank. He has been drawing down on a retirement account, worth nearly $2.5 million in 2022. It had just over $1 million in May.