Bubble in the Sun: The Florida Boom of the 1920s and How It Brought on the Great Depression (Christopher Knowlton) explains how Miami Beach was essentially the vision of a single individual, Carl Fisher (a pioneer in automobile headlights, highway development, and co-founder of the Indy 500).

Jane believed the project would be an expensive mistake. When Fisher took her to inspect the property by boat, they entered from the bay side, rowing up a channel lined with dense mangroves. “Mosquitos blackened our clothing,” she wrote. “Jungle flies, as large as horse flies, waited for our blood.… Other creatures that made me shudder were lying in wait in the slimy paths or on the branches of overhanging trees. The jungle itself was as hot and steamy as a conservatory.… What on earth could Carl possibly see in such a place?” But Fisher insisted that he knew what he was doing. Standing with her on the soft sand on the ocean side of the long neck, the surf breaking toward them in slow, white rollers, he sketched out his vision for the area. It would be half beach resort and half playground. “In that moment, Carl’s imagination saw Miami Beach in its entirety, blazing like a jewel with hibiscus, oleander, poinsettia, bougainvillea, and orchids, feathered with palms and lifting proud white towers against the sky,” Jane recalled. “But I looked at that rooted and evil-smelling morass and had nothing to say. There was nothing a devoted wife could say.”

As 1919 unfolded, Carl Fisher made two final and critical changes to his business strategy. The first was to switch his target audience, which had always been the elderly and the retired rich, most of whom still favored Palm Beach over Miami, and always would. As he told Business magazine a few years later, “I was on the wrong track. I had been trying to reach the dead ones. I had been going after the old folks. I saw that what I needed to do was go after the live wires. And the live wires don’t want to rest.” He would concede the superrich and the old money to Palm Beach. Instead, Miami Beach would be for the nouveau riche; for men like Fisher himself, especially those from the industrial Midwest; men who were younger, still making their fortunes, and looking for fun ways to spend their new wealth. He would appeal to them with the sort of activities that appealed to him: contests, races, and other events that featured sports celebrities. Henceforth, Miami Beach would become “a youthful city of indeterminate social standing,” in the words of social historian Charlotte Curtis. Fisher’s second change in tactics was equally radical: he raised his land prices by 10 percent, in part to give the appearance that his lots were appreciating rapidly in value. And to further promote that perception, he offered a return guarantee of 6 percent “to any customer in Miami or elsewhere who purchased lots from us and are not well pleased with their investment.” He assured his buyers that, from then on, he would be raising prices by 10 percent every year. Ten percent was an exceptionally attractive rate of return; 10 percent that seemed virtually guaranteed was even more attractive. Fisher, in trying to stoke a small fire, was about to fuel a conflagration. Behind the scenes, other factors had contributed to the marked improvement in sales. Chief among these was the wide proliferation of the automobile. The machines that Fisher had raced, sold, and promoted back in Indiana had evolved into bona fide consumer products, viable and cost-effective substitutes for the horse and buggy. The automobile, more than the railroad, the streetcar, or any other factor, turned the American landscape from raw land into real estate. It did so by making the land accessible and thus developable: its value could be easily established, enhanced, and commodified. Land then became a far more salable product, one that benefited landlords, lenders, contractors, and real estate agents, to say nothing of the purchasers and renters of that property. Nowhere was this truer than in Florida. And nowhere in Florida was it truer than in Miami Beach, where the road built over the Collins Bridge and the new County Causeway (renamed MacArthur Causeway in 1942) at last made the resort developments there commercially viable—by making them accessible to cars. Miami Beach was on its way to becoming the most widely publicized and most famous resort destination in the country. Fisher was now forty-three years old but still full of vitality. “This is only the beginning,” he announced presciently in an ad that appeared in the Miami Metropolis newspaper late in 1919, adding that he planned to further enhance Alton Beach the following year with “a polo club house, a church, theater, schoolhouse, six store buildings, and ten Italian villas ranging from $10,000 to $35,000 each.”

By the mid-1920s, Fisher’s vision was more or less realized:

In her memoirs, Fabulous Hoosier, Carl’s first wife, Jane, captures the surreal nature of the late boom years and how the clientele of their once sleepy resort town had changed: “Pouring into Miami Beach they came, fantastic visitors to a fantastic city. The gold diggers and the sugar daddies, the gigolos, the ‘butter and egg men,’ the playboys and the gilded heiresses, the professional huntresses, the tired businessmen who never grew tired, the gentlemen who preferred blonds. Miami Beach was the playground of millionaires and the happy hunting ground of predatory women.”

Then he tried to do it all over again in Montauk, Long Island and, due to leverage, blew up. The book chronicles the fate of other folks who became billionaires (in today’s debased money) from their efforts in Florida real estate, e.g., George E. Merrick who planned and built Coral Gables and Addison Mizner who is responsible for the Spanish-style architecture that we now see all over Florida. Essentially all of them went bust after staking their fabulous riches on yet more expansion.

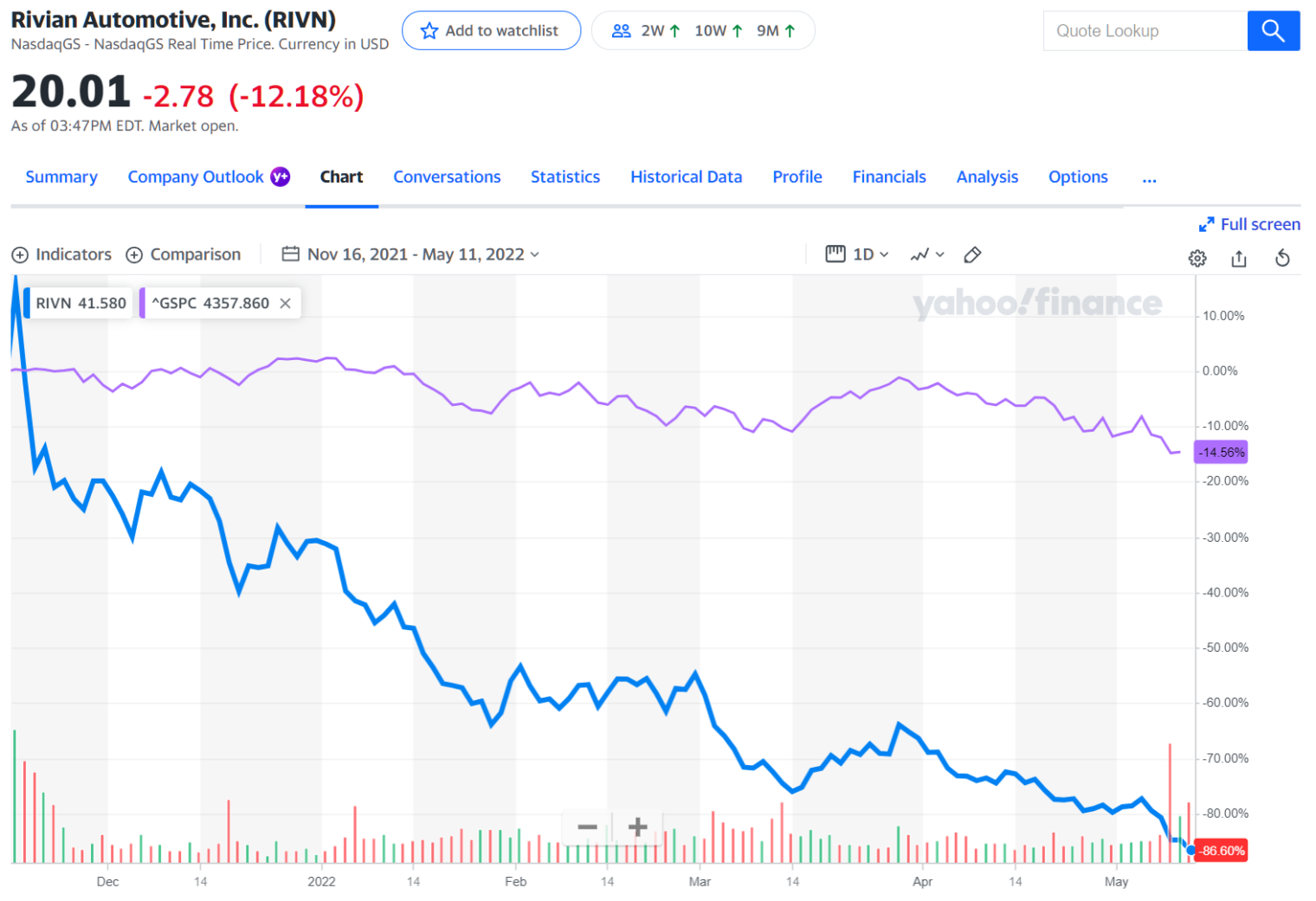

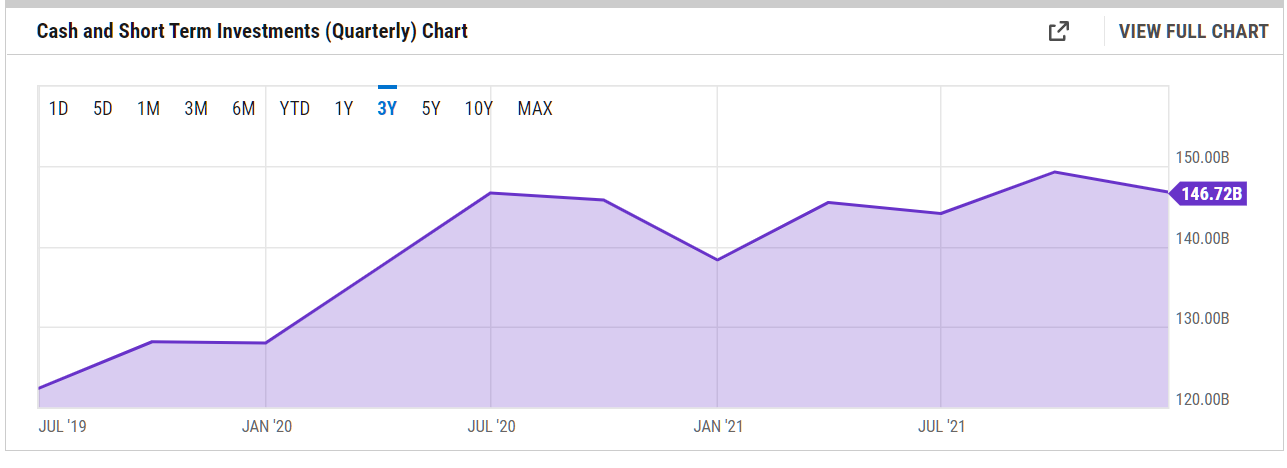

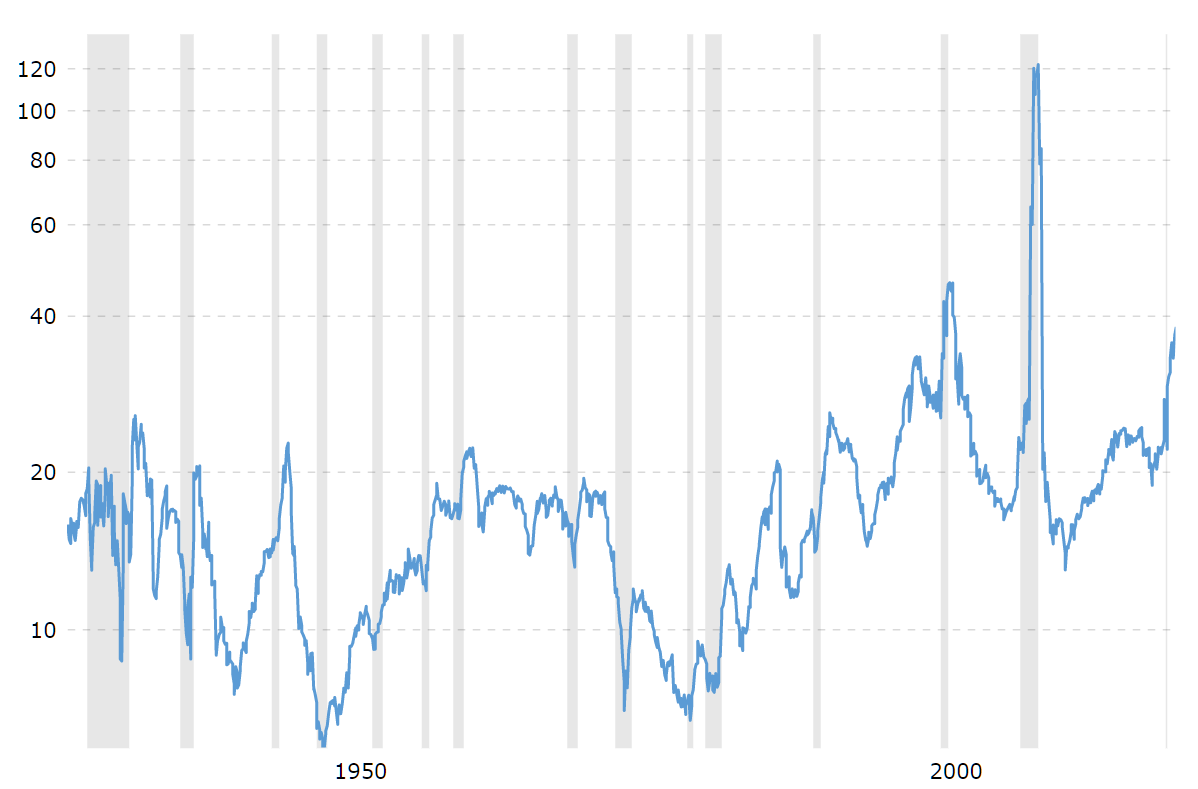

What’s the worst that can happen in our current real estate and stock market boom? A retired hedge fund manager friend says that he wouldn’t be shocked to see a 90 percent crash. I think that this is excessive given that Manhattan real estate crashed by only 67 percent from 1929 to 1932 (HBS) and this was much steeper than the nationwide decline.

The book should be an inspiration for more diversification, though 2008 showed how tough that can be to achieve. Here are some $5-12 million houses (Jupiter Inlet Colony) to enjoy while the good times last…

Related:

Full post, including comments