A book about the Federal Reserve and inflation

A timely book… The Lords of Easy Money: How the Federal Reserve Broke the American Economy (2022) by Christopher Leonard.

Motivation…

First, since this is a political book let’s look at the author’s background politics. He is particularly hostile to the Tea Party,

If the Tea Party had a single animating principle, it was the principle of saying no. The Tea Partiers were dedicated to halting the work of government entirely.

An aging population relied more and more heavily on underfunded government programs like Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security,

The existence of these Deplorables kept the reasonable Democrats and Republicans in Congress from doing great work via government spending, thus putting pressure on the Fed to act. The Fed’s rash actions may thus be laid at least partly at the doors of the haters. Also, the best characterization of the world’s most expensive health care programs, as a percentage of GDP, is “underfunded”. Without the Tea Party, every Medicaid beneficiary would get a weekly gender reassignment surgery? The author expresses his dream that more American workplaces would become unionized.

What’s the scale of the Fed’s recent money-printing?

Between 1913 and 2008, the Fed gradually increased the money supply from about $5 billion to $847 billion. This increase in the monetary base happened slowly, in a gently uprising slope. Then, between late 2008 and early 2010, the Fed printed $1.2 trillion. It printed a hundred years’ worth of money, in other words, in little over a year, more than doubling what economists call the monetary base.

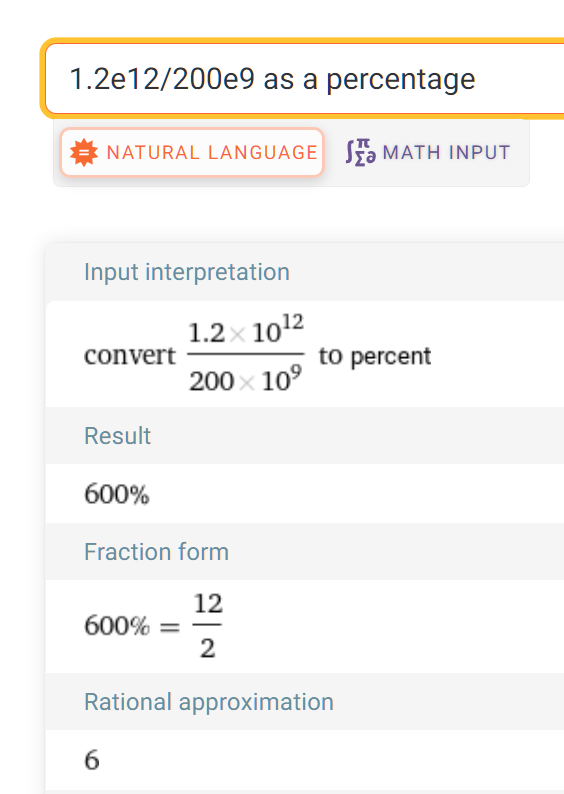

The amount of excess money in the banking system swelled from $200 billion in 2008 to $1.2 trillion in 2010, an increase of 52,000 percent.

Maybe the author and Simon and Schuster are using coronamath? What if they’d asked Wolfram Alpha about this ratio? The answer would be a 600 percent ratio or 500 percent increase, not 52,000 percent.

Whatever the percentage might have been, quantitative easing was going to be good news for the rich:

The FOMC debates were technical and complicated, but at their core they were about choosing winners and losers in the economic system. Hoenig was fighting against quantitative easing because he knew that it would create historically huge amounts of money, and this money would be delivered first to the big banks on Wall Street. He believed that this money would widen the gap between the very rich and everybody else. It would benefit a very small group of people who owned assets, and it would punish the very large group of people who lived on paychecks and tried to save money.

Perhaps no single government policy did more to reshape American economic life than the policy the Fed began to execute on that November day, and no single policy did more to widen the divide between the rich and the poor. Understanding what the Fed did in November 2010 is the key to understanding the very strange economic decade that followed, when asset prices soared, the stock market boomed, and the American middle class fell further behind.

According to the book, Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen (U.S. Treasury Secretary today, at least until my prediction of Sam Bankman-Fried taking over comes true) were the Fed’s biggest cheerleaders for quantitative easing while Thomas M. Hoenig was the biggest opponent, partly due to concerns about inflation, but mostly because the “allocative effect” in which money would move from working class to rich and from people who did productive things to Wall Street.

[Bernanke is most notable for his 2007 statement: “We believe the effect of the troubles in the subprime sector on the broader housing market will likely be limited and we do not expect significant spillovers from the subprime market to the rest of the economy or to the financial system.”]

How does QE work?

The basic mechanics and goals of quantitative easing are actually pretty simple. It was a plan to inject trillions of newly created dollars into the banking system, at a moment when the banks had almost no incentive to save the money. The Fed would do this by using one of the most powerful tools it already had at its disposal: a very large group of financial traders in New York who were already buying and selling assets from the select group of twenty-four financial firms that were known as “primary dealers.” The primary dealers have special bank vaults at the Fed, called reserve accounts.II To execute quantitative easing, a trader at the New York Fed would call up one of the primary dealers, like JPMorgan Chase, and offer to buy $8 billion worth of Treasury bonds from the bank. JPMorgan would sell the Treasury bonds to the Fed trader. Then the Fed trader would hit a few keys and tell the Morgan banker to look inside their reserve account. Voila, the Fed had instantly created $8 billion out of thin air, in the reserve account, to complete the purchase. Morgan could, in turn, use this money to buy assets in the wider marketplace.

Bernanke’s initial goals were to create $600 billion via QE, with the justification that this would bring down unemployment. “Before the crisis [of 2008], it would have taken about sixty years to add that many dollars to the monetary base.”

The Fed’s own research on quantitative easing was surprisingly discouraging. If the Fed pumped $600 billion into the banking system, it was expected to cut the unemployment rate by just .03 percent.

Who had the best crystal ball?

Jeffrey Lacker, president of the Richmond Fed, said [in 2010] the justifications for quantitative easing were thin and the risks were large and uncertain. “Please count me in the nervous camp,” Lacker said. He warned that enacting the plan now, when there was no economic crisis at hand, would commit the Fed to near-permanent intervention as long as the unemployment rate was elevated. “As a result, people are likely to expect increasing monetary stimulus as long as the level of the unemployment rate is disappointing, and that’s likely to be true for a long, long time.”

[Richard] Fisher, the Dallas Fed president, said he was “deeply concerned” about the plan. Of course, he didn’t let pass the chance to use a nice metaphor: “Quantitative easing is like kudzu for market operators,” he said. “It grows and grows and it may be impossible to trim off once it takes root.” Fisher echoed Hoenig’s warnings that the plan would primarily benefit big banks and financial speculators, while punishing people who saved their money for retirement. “I see considerable risk in conducting policy with the consequence of transferring income from the poor, those most dependent on fixed income, and the saver to the rich,” he said.

What’s wrong with massive asset price inflation, as the Fed was trying to achieve? The author says that asset price bubbles are the typical drivers of both banking and market collapses. Example from the 1980s:

When Paul Volcker and the Fed doubled the cost of borrowing, the demand for loans slowed down, which in turn depressed the demand for assets like farmland and oil wells. The price of assets began to converge with the underlying value of the assets. The price of farmland fell by 27 percent in the early 1980s; of oil, from more than $120 to $25 by 1986. The collapse of asset prices created a cascading effect within the banking system. Assets like farmland and oil reserves had been used to underpin the value of bank loans, and those loans were themselves considered “assets” on the banks’ balance sheets. When land and oil prices fell, the entire system fell apart. Banks wrote down the value of their collateral and the reserves they were holding against default. At the very same moment, the farmers and oil drillers started having a hard time meeting their monthly payments. The value of crops and oil were falling, so they earned less money each month. The banks’ balance sheets, which once looked stable, began to corrode and falter.

This was the dynamic that so often gets lost in the discussion about the inflation of the 1970s and the collapse and recession of the 1980s. The Fed got credit for ending inflation, and for bailing out the solvent banks that survived it. But new research published many decades later showed that the Fed was also responsible for the whole disaster.

Why don’t people get nervous when an asset bubble is inflating?

When asset inflation gets out of hand, people don’t call it inflation. They call it a boom. Much of the asset inflation of the late 1990s was showing up in the stock market, where share prices were rising at a level that would have been horrifying if it was expressed in the price of butter or gasoline. The entire Standard & Poor’s stock index rose by 19.5 percent in 1999. The Nasdaq index, which measured technology stocks, jumped more than 80 percent.

When asset bubbles burst, the Fed is right there:

Over the next two years [after the dotcom crash of 2000], the Federal Reserve’s state of emergency became almost permanent. The rate cuts of 2001 remained in place, with the cost of short-term loans staying below 2 percent until the middle of 2004.

As with coronapanic, dramatic efforts for short-term relief lead to long-term disaster:

If there was one thing Hoenig had learned, it was that the Fed’s leaders, who were only human, tended to focus on short-term events and the headlines that surrounded them. But the Fed’s actions were expressed in the real world over the long term, after they had time to work their way through the financial system. When there was turmoil in the markets, the Fed leaders wanted to take immediate action, to do something. But their actions always played out over months or years and tended to affect the economy in unexpected ways.

The book was written before the Silicon Valley Bank collapse, but does this sound familiar?

The Fed was essentially coercing hedge funds, banks, and private equity firms to create debt and do it in riskier ways. The strategy was like a military pincer movement that closes in on the opponent from two sides—from one direction there was all this new cash, and from the other direction there were the low rates that punished anyone for saving that cash.

Before the financial collapse that started in 2007, the reward for saving money in a 10-year Treasury was 5 percent. By the autumn of 2011, the Fed helped push it down to about 2 percent.I The overall effect of ZIRP [zero-interest-rate policy] was to create a tidal wave of cash and a frantic search for any new place to invest it. The economists called this dynamic the “search for yield” or a “reach for yield,” a once-obscure term that became central to describing the American economy.

Then, as now, the nation’s problems started in San Francisco:

One of Bernanke’s secret weapons in the lobbying effort was his vice chairwoman, Janet Yellen, the former president of the San Francisco Fed. Yellen was an assertive and convincing surrogate for Bernanke, and she championed an expansive use of the Fed’s power.

“Janet was the strongest advocate for unlimited” quantitative easing, [Elizabeth] Duke recalled. “Janet would be very forceful. She is very confident, very strong in promoting the point of view.” Yellen and Bernanke were convincing, and their argument rested on a simple point. In the face of uncertainty, the Fed had to err on the side of action.

If it is any comfort, the Europeans are even dumber and more devoted to cheating with money instead of working harder than we are:

Full post, including commentsIn Europe, the financial crisis of 2008 had never really ended [by 2012]. The debt overhang in Europe was simply astounding. Just three European banks had taken on so much debt before 2008 that their balance sheets