Inflation ideas roundup

Having fizzled out, at least on a month-to-month basis (see Inflation of 0 percent reported as inflation of 8.5 percent), inflation got a big boost today when Joe Biden decreed that some members of the laptop class won’t ever have to pay back up to $20,000 of student loans (the debt will be transferred to Walmart cashiers and other working class chumps) and nobody needs to pay student loans until the end of 2022 (and no interest will accrue). From studentaid.gov:

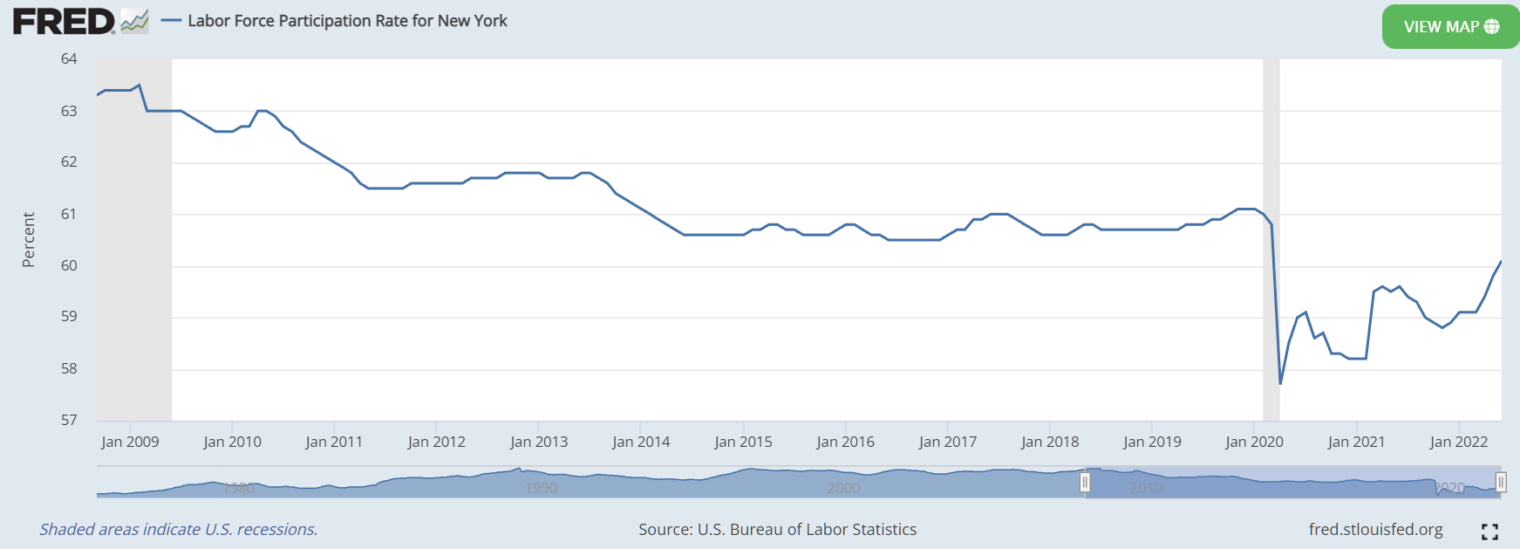

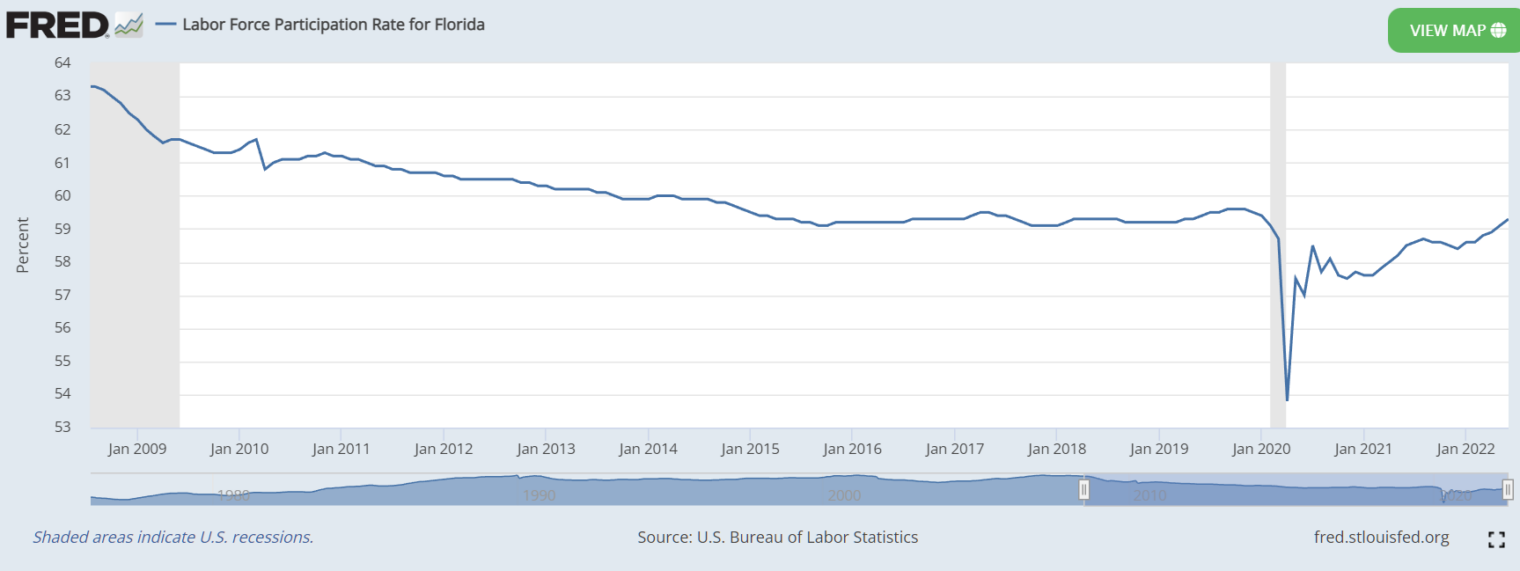

“no one with a federally held loan has had to pay a single dollar in loan payments since President Biden took office.” I think that this is the more significant driver of near-term inflation. If no one has had to pay a single dollar in loan payments then no one needs to put down the Xbox controller, leave mom’s basement, and look for a job. An employer will have to keep bidding up wages in order to woo some of the limited number of Americans who’ve decided, perhaps out of habit, to stay in the labor force.

With Americans anxious about inflation, how could it make political sense for a politician to do something that will obviously stoke inflation? Nate Silver explains why this is not an irrational move for a federal government run by Democrats:

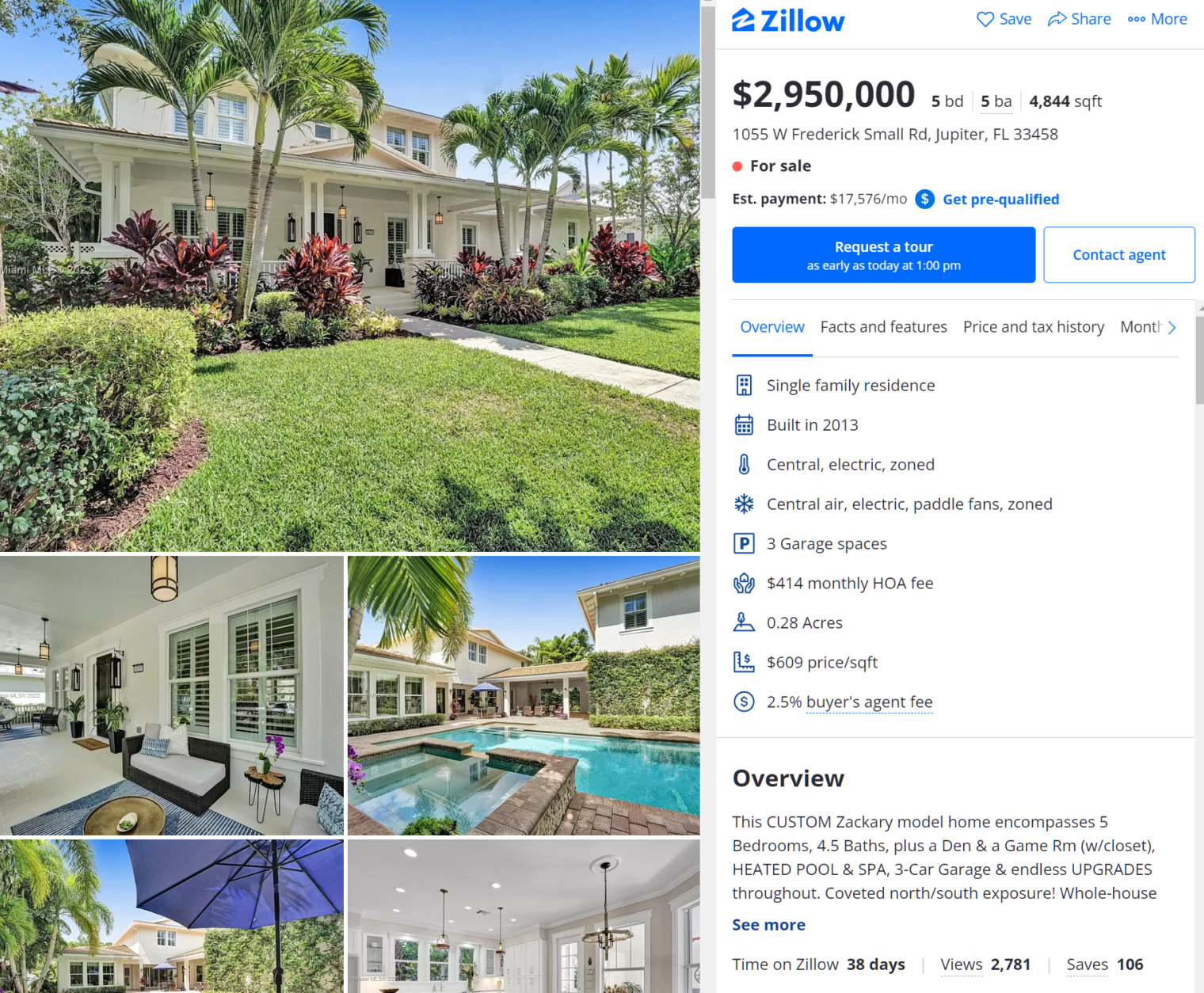

Note the “redistribute well-being” from the working class to the laptop class, just as low-skill immigration does according to a Harvard prof and just as the newly expanded $7,500 electric vehicle tax credit does. I’m beginning to wonder how much more the working class can be made to pay to the laptop class. In which year of the Biden administration does the Walmart cashier begin to have to subsidize the laptop class member’s purchase of a new fuel-efficient Cirrus airplane?

Economists are back to their multiple hands… “Nobody Knows How Interest Rates Affect Inflation” (WSJ, 8/24, John H. Cochrane):

Conventional wisdom says that as long as interest rates are below the rate of inflation, inflation will rise. Inflation in July was 8.5%, measured as the one-year change in the consumer price index. The Fed has raised the federal funds rate only from 0.08% in March to 2.33% in August. According to the conventional view, that isn’t nearly enough. Higher rates are needed, now.

This conventional view holds that the economy is inherently unstable. The Fed is like a seal, balancing a ball (inflation) on its nose (interest rates). To keep the ball from falling, the seal must quickly move its nose.

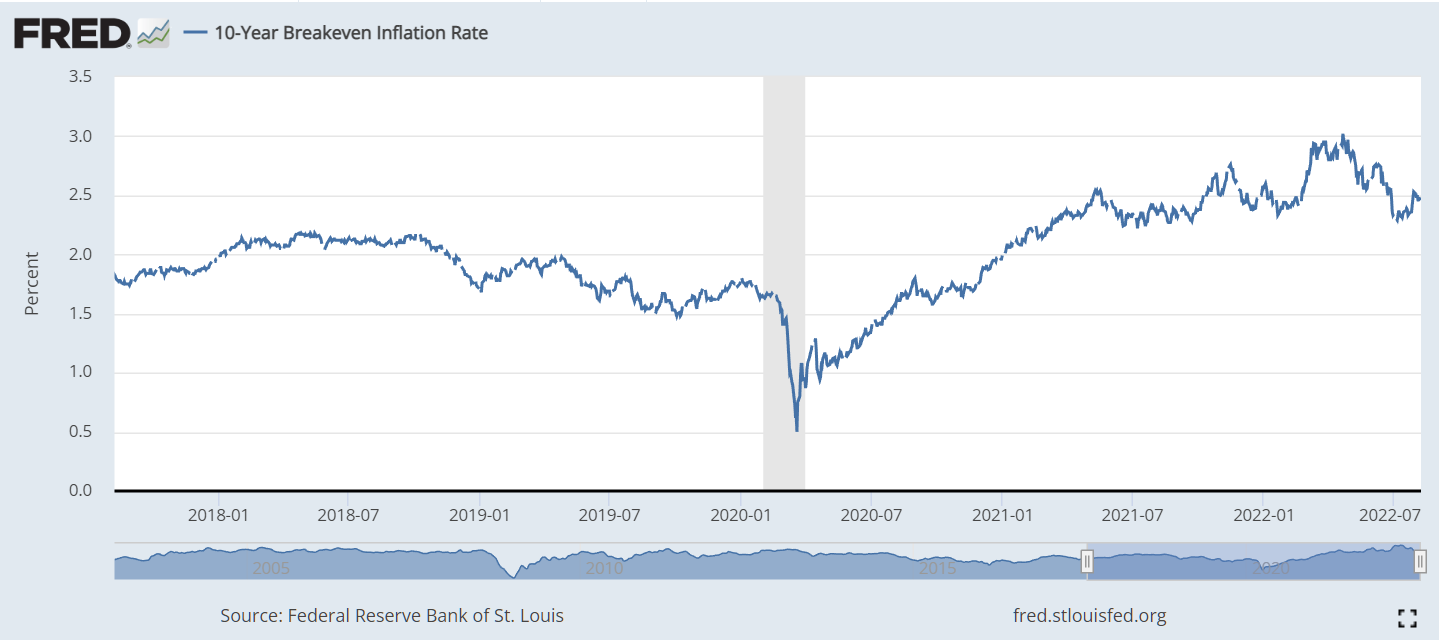

In a newer view, the economy is stable, like a pendulum. Even if the Fed does nothing, so long as there are no more shocks, inflation will eventually peter out. The Fed can reduce inflation by raising interest rates, but interest rates need not exceed inflation to prevent an inflationary spiral. This newer view is reflected in most economic models of recent decades. It accounts for the Fed’s projections and explains the Fed’s sluggish response. Stock and bond markets also foresee inflation fading away without large interest-rate rises.

The learned and credentialed author concludes with no conclusion about who is right. Even our most notable economists aren’t going to get rich via financial market trades, it seems, based on their superior predictive abilities for inflation rates.

Also from the WSJ, but written by a journalist rather than an economist, “Jerome Powell’s Dilemma: What if the Drivers of Inflation Are Here to Stay?”:

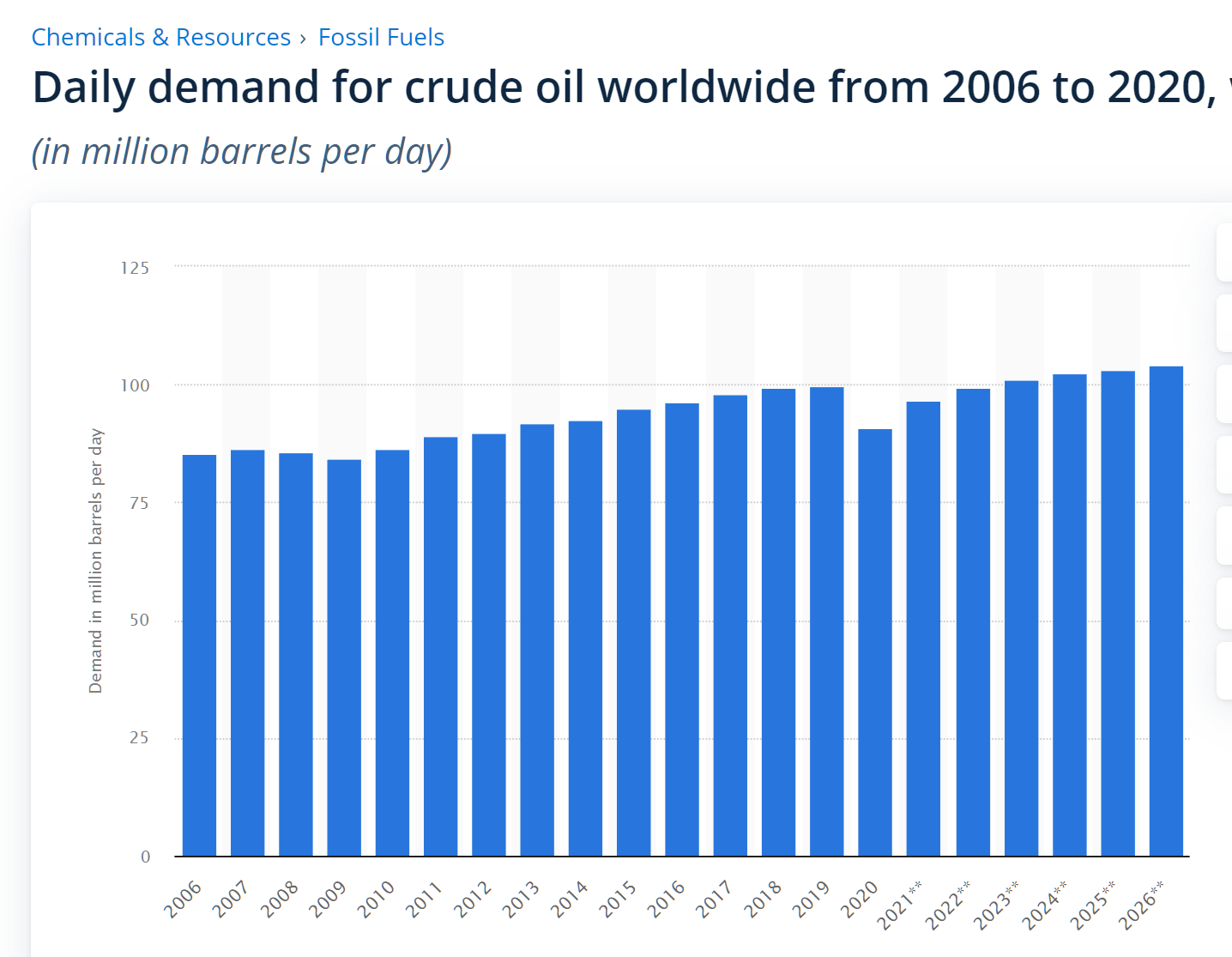

In an August 2020 book, “The Great Demographic Reversal,” former British central banker Charles Goodhart and economist Manoj Pradhan argued that the low inflation since the 1990s had less to do with central-bank policies and more with the addition of hundreds of millions of low-wage Asian and Eastern European workers, which held down labor costs and prices of manufactured goods exported to richer countries.

Mr. Goodhart wrote that global labor glut was giving way to an era of worker shortages, and hence higher inflation.

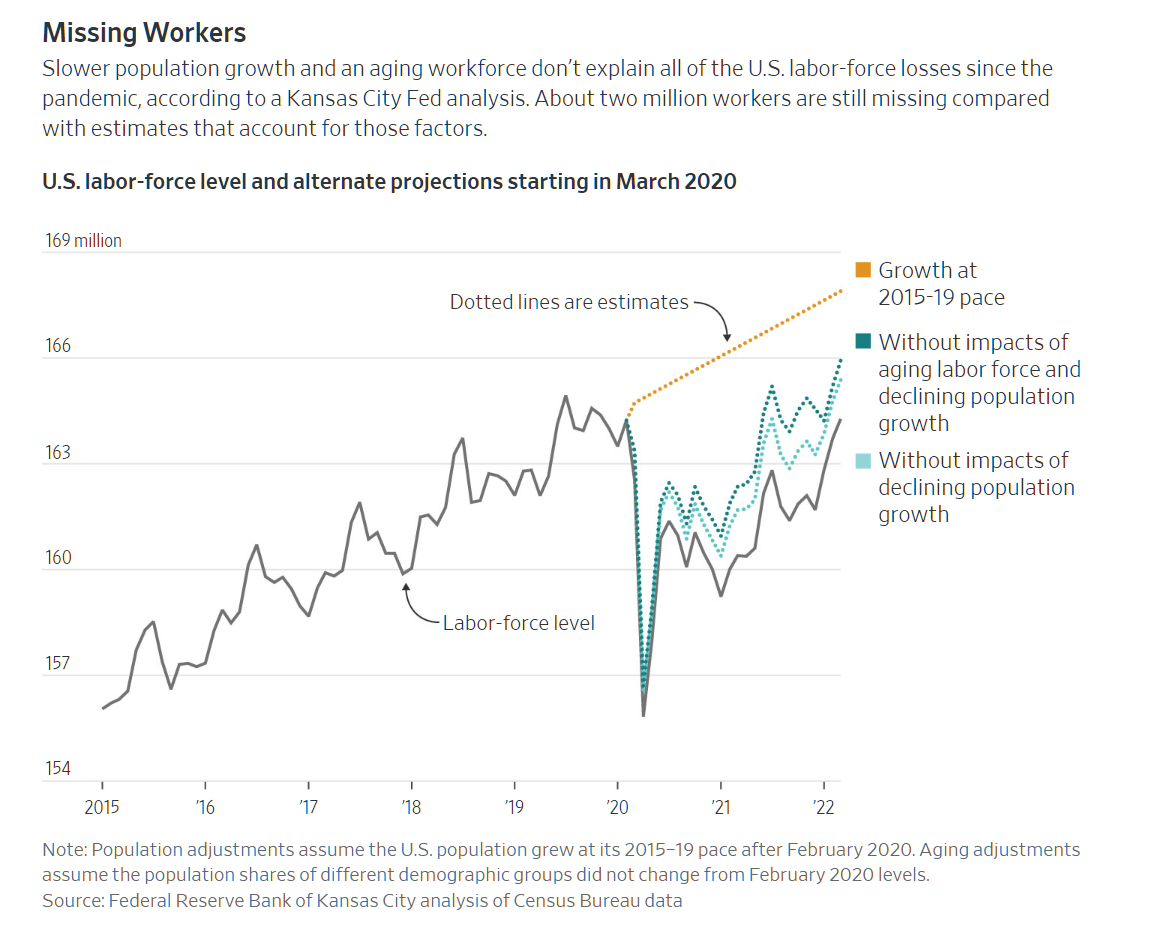

Meanwhile, the U.S. labor force has roughly 2.5 million fewer workers since the pandemic began, compared with what it would have if the prepandemic trend in workforce participation had continued and after accounting for the aging of the population, according to an analysis by Didem Tüzemen, an economist at the Kansas City Fed.

The low-inflation environment of the past 30 years caused consumers and businesses to not think much about price increases. Fed officials now worry that even if prices rise temporarily, consumers and businesses could come to expect higher inflation to persist. That could help fuel higher inflation as workers demand higher pay that employers would pass onto consumers through higher prices.

The expert witness world could serve as an example for the last paragraph. An expert witness engagement usually lasts no more than 3 years and, with inflation expectations low, it was conventional for a contract to call for a fixed rate for the entire engagement. Starting in 2022, however, it became conventional for contracts to allow for annual price increases.

[I should do a separate blog post at some point about how economists don’t seem to account for human nature in forecasting labor force participation. The assumption is that humans don’t get habituated to either working or not working. So an American will jump in and out of the labor force as soon as wages or conditions are adjusted. The American’s value of leisure time will be constant and won’t depend on whether the American has just spent the last two years not working, participating in a bunch of online games, in-person clubs and leagues, etc. Because of this flawed model of humans, economists are surprised on a daily basis that higher wages haven’t lured more Americans back into the labor force. There is nothing in the economics models that says if you play a lot of Xbox for a year you will get better at Xbox and enjoy playing Xbox more and, therefore, require a higher wage to tempt you out of the house.]

Related: