Texans are suffering with cold weather, power failure, and water supply failure. (In other words, they’re learning what it is like to live in the Northeast; see, for example, the 2011 storm that took out power for 3.2 million people, many of whom went a week without power. In the Boston suburbs it is typical to lose power 4-6 times per year, e.g., due to a fallen tree or a storm, and for durations of up to 48 hours. Also 2013 and 1978 events, in the latter of which more than 100 people died.)

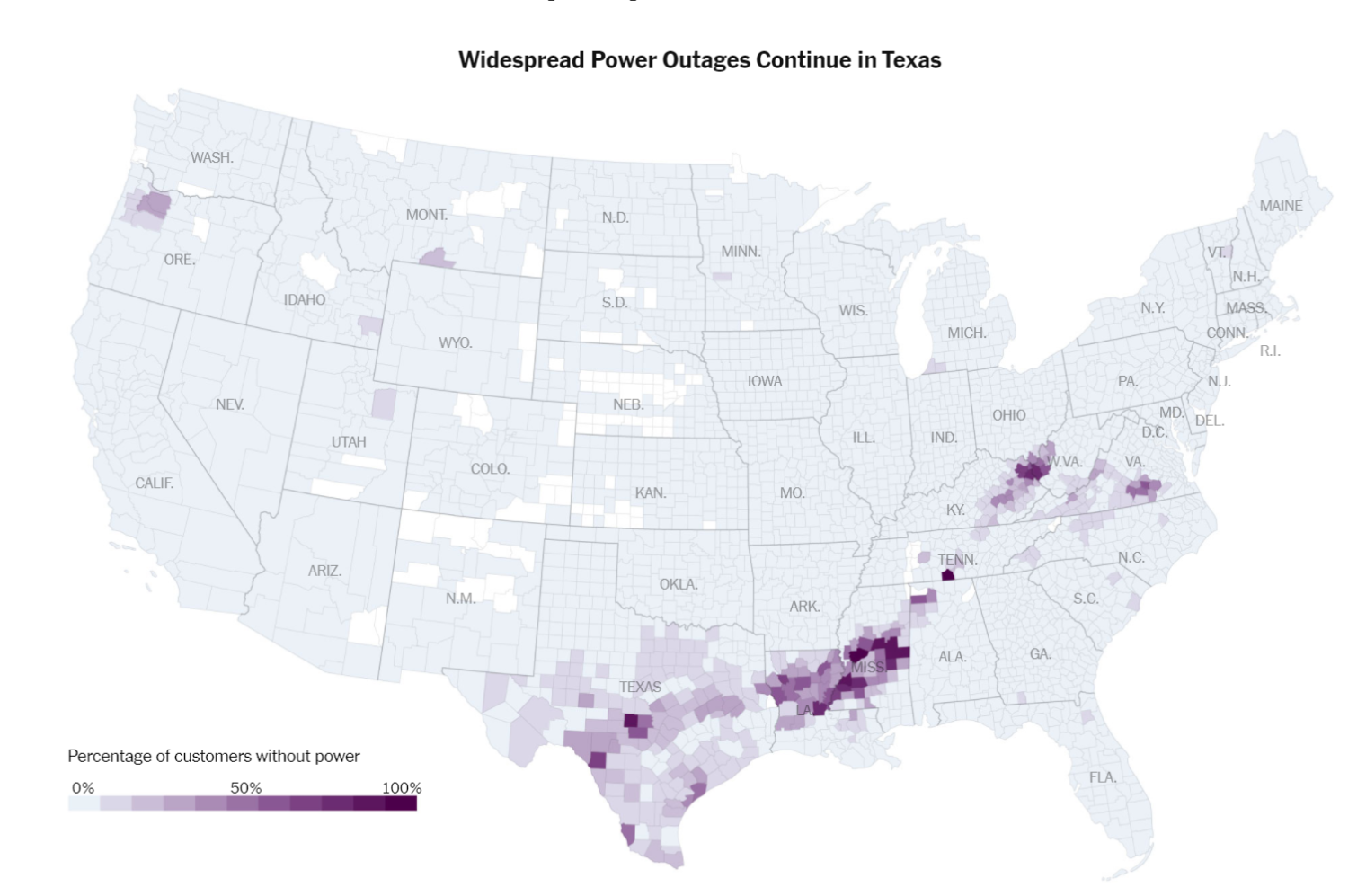

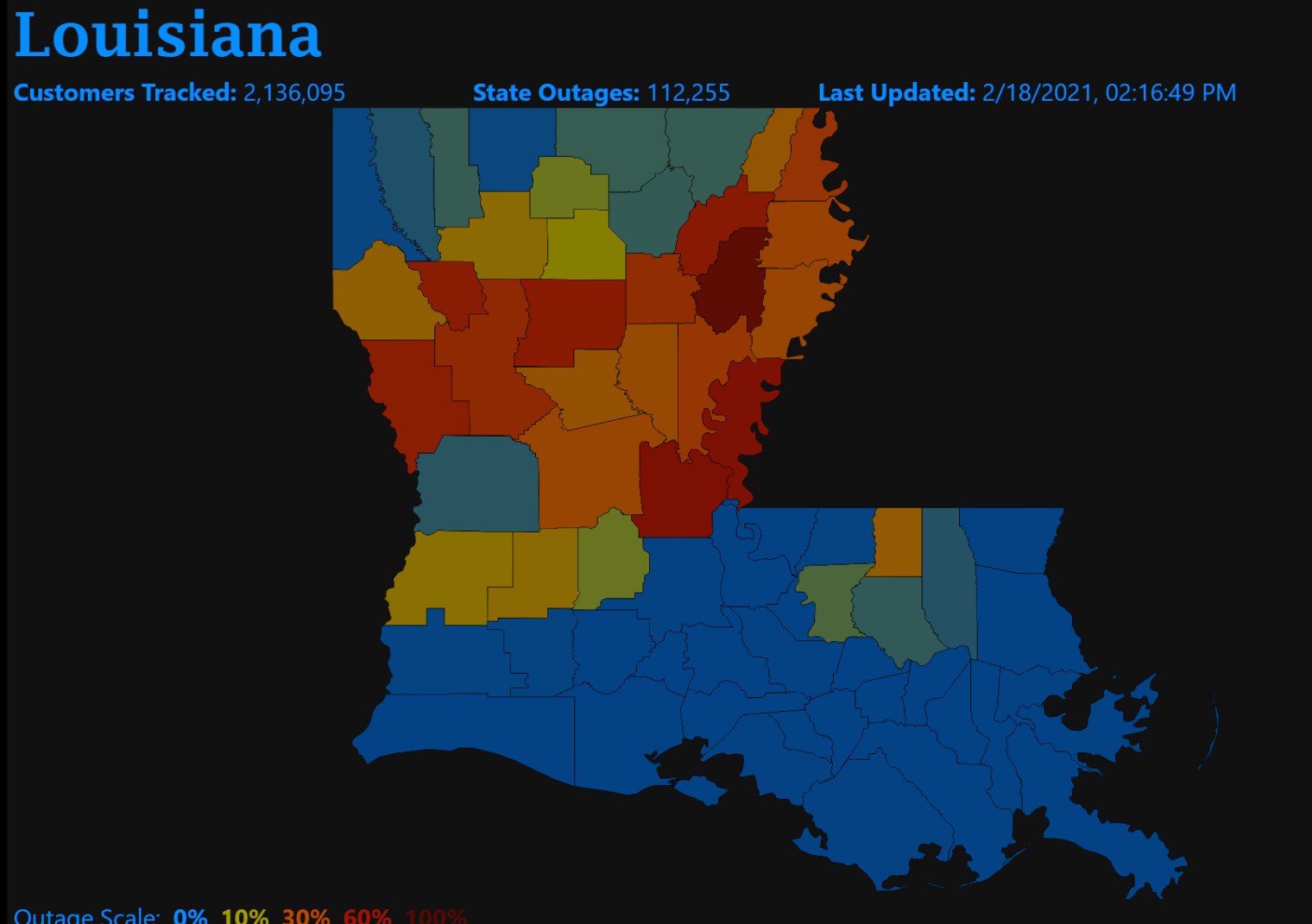

(That we’re calling this the “Texas power outage” might be an artifact of how our media presents things. “Widespread Power Outages Continue in Texas” is the caption the New York Times editors have placed over a map showing that the worst outages are in Louisiana and Mississippi:

)

The media can find an unlimited number of folks who describe this as a trivially foreseeable event, e.g., “Why Texas’ energy grid is unable to handle the winter storms” (NBC):

The crisis has made the state’s energy grid the focus of fresh scrutiny, primarily due to its independence from the rest of the U.S. Critics say that allowed its infrastructure to shirk federal regulations that require cold-weather capabilities.

Heroic regulators could have prevented this from happening? The governor agrees! “‘Massive failure’: Why are millions of people in Texas still without power?” (USA Today):

At the most basic level, the outages have been caused because demand amid the bitter cold has outpaced the supply of energy used to heat and power homes, said Daniel Cohan, an associate professor of civil and environmental engineering at Rice University.

Gov. Greg Abbott called the situation “unacceptable” and said he would add an emergency item to the state’s legislative session on reforming ERCOT. The nonprofit corporation is subject to oversight from the Public Utility Commission of Texas and the Legislature.

There were similar events in 1989 and 2011… “Five things to know about Texas’s strained electric grid” (The Hill):

The 1989 blackouts came amid a cold snap in December, while the 2011 blackouts took place during the first week of February when wind and unseasonably cold temperatures hit Texas and neighboring New Mexico.

In total, approximately 1.3 million electric customers were out of service at the peak of the 2011 event on Feb. 2, and a total of 4.4 million were affected from Feb. 2 to Feb. 4.

In a report following the 2011 blackouts, FERC and the North American Electric Reliability Corporation recommended steps including increasing winterization measures.

The report said electricity generating companies operating within the ERCOT system “failed to adequately prepare for winter,” citing inadequate insulation and a failure to train operators and maintenance personnel on winter preparations.

If this was easy to foresee (and maybe it should have been, given what happened in 1989 and 2011), why weren’t these newspapers and interview subjects out there at least since 2011 beating the drum for more power plants and more winterization of infrastructure?

Could there be a general principle in operation here? After a hurricane hits, it is obvious that we should have put vastly more resources into being prepared for the hurricane. After a bad respiratory virus pandemic, it is obvious that we should have put vastly more resources into stockpiling PPE and ventilators (see Paper titled “Stockpiling Ventilators for Influenza Pandemics” (2017)).

Here in the Northeast we know that we could eliminate nearly all of our outages via putting power lines underground, but nobody wants to pay for it. This utility explains:

The main reason why undergrounding hasn’t been fully adopted in the U.S. is the overwhelmingly high cost of installing underground power lines. Estimates place the cost of undergrounding power lines at roughly $750 per foot, compared with $70 per foot to install power lines the way we do today. At over ten times the cost, this would become expensive very quickly.

Take North Carolina, for example. In 2002, the state looked into undergrounding for their three major power companies after a particularly bad power outage that left 2 million people losing power. After it was priced out, North Carolina found that their project would cost $41 billion (six times the net value of those three companies’ distribution assets) and would require 25 years to complete!

People are regularly killed during power outages. Should we pay any price, bear any burden to save lives via underground power lines? Apparently not. (Even though $41 billion rounds to zero in coronanomics!)

Why can’t people see that (1) we don’t have infinite money and time and therefore can’t be prepared for everything bad that might happen, and (2) they’re using hindsight when they talk about how we should have put more resources into preparing against something bad that actually did happen?

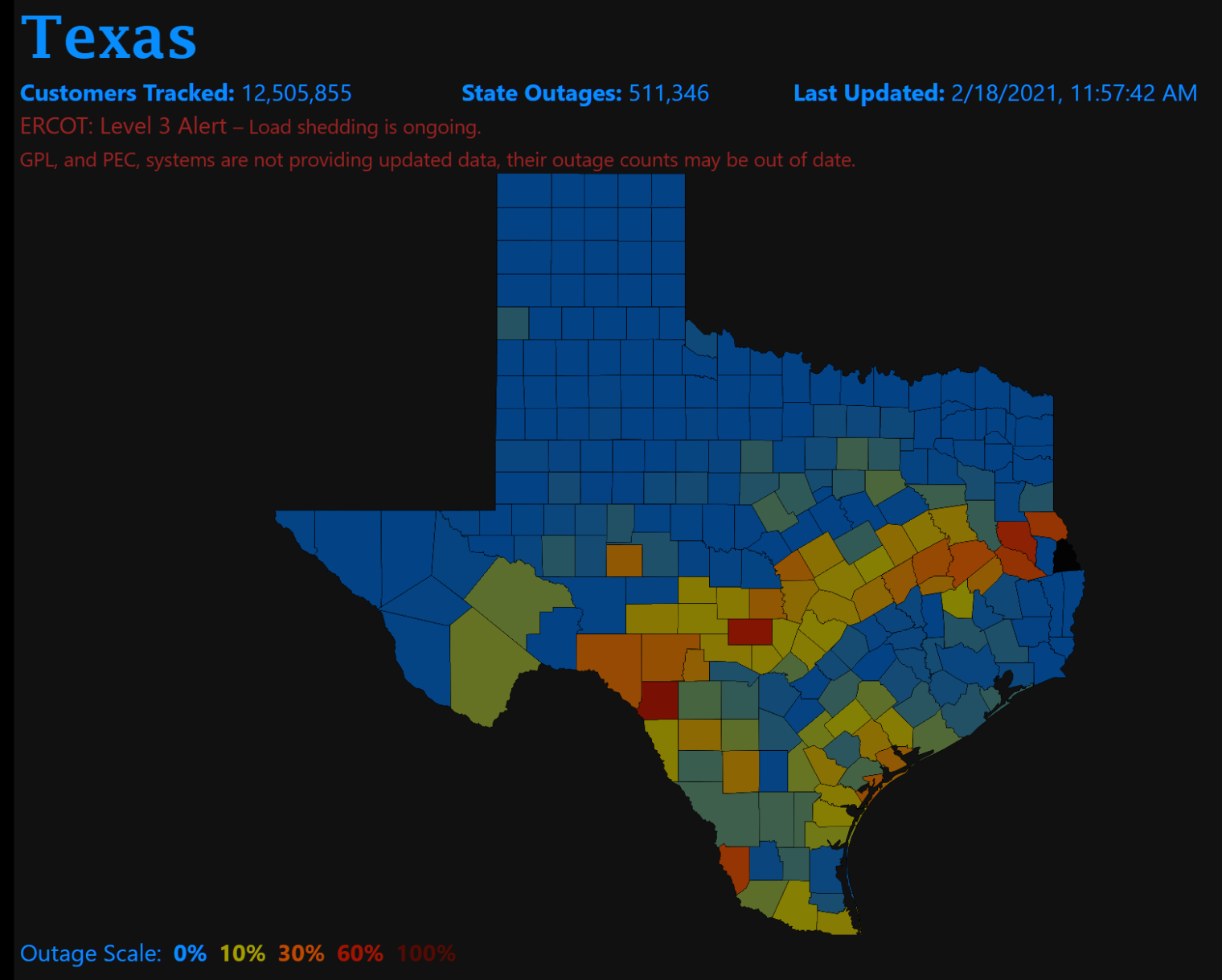

As of yesterday, 4 percent of total customers (poweroutage.us), but I am pretty sure that this figure will never appear in a headline (since Texas has such a huge population the outage will appear as the total number of customers who are out).

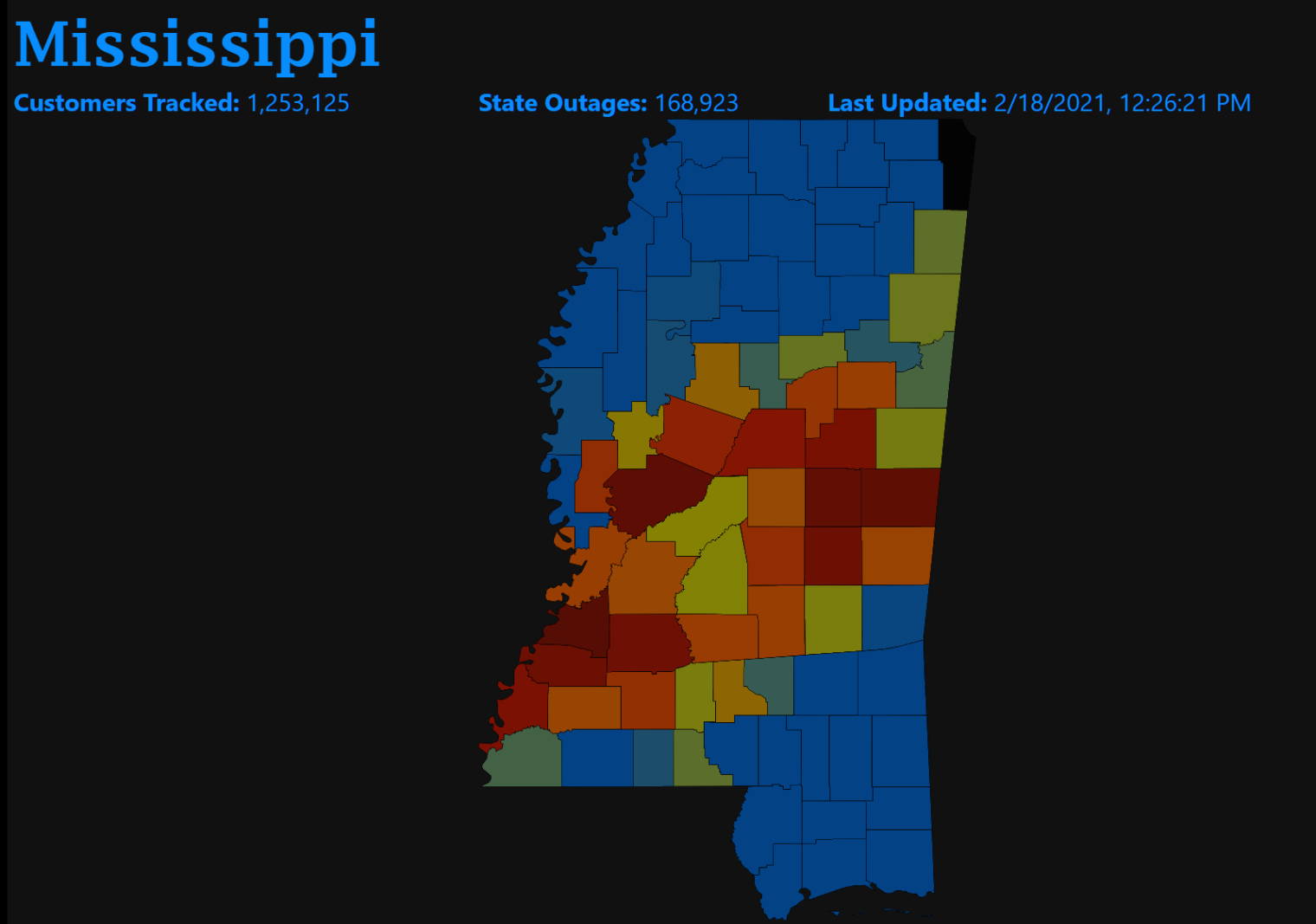

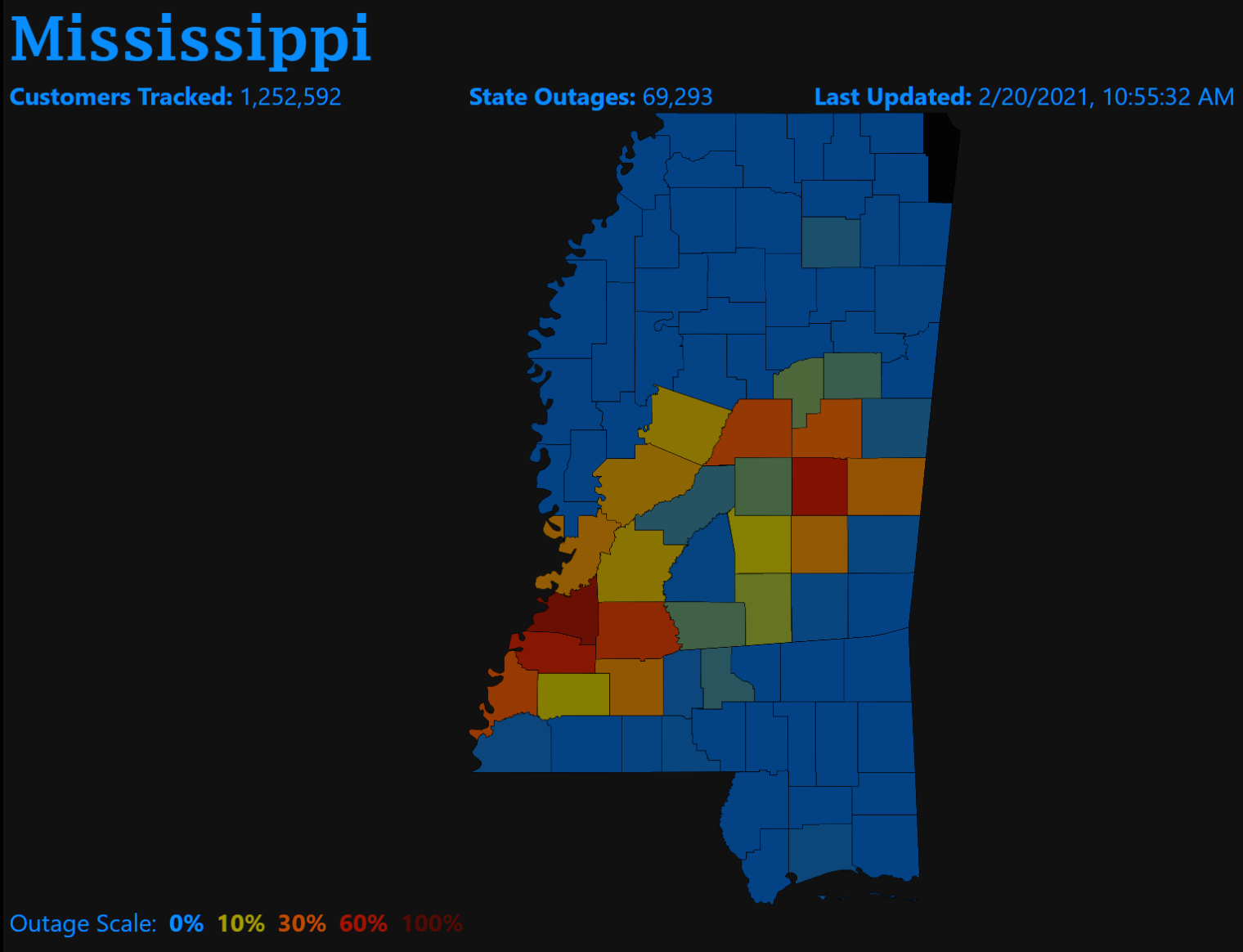

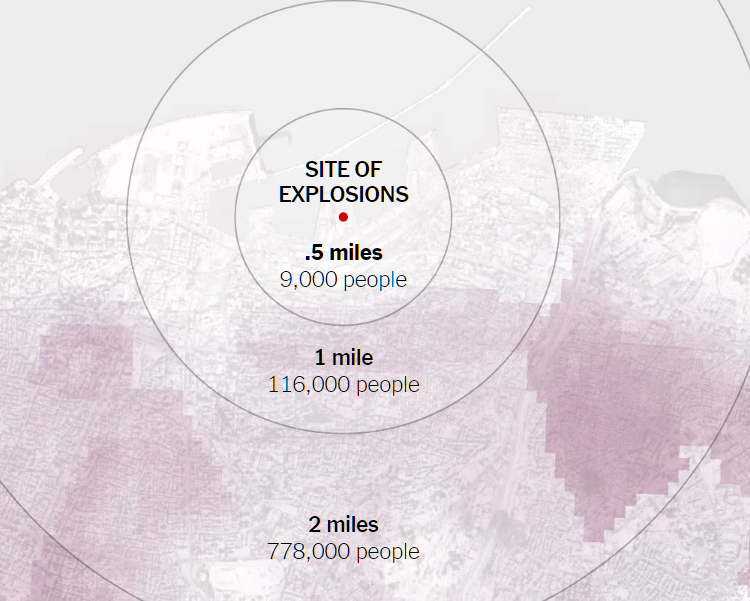

I asked a California Democrat (and tenured physics professor), who was expressing outrage that the Texas grid wasn’t subject to federal regulation, what he thought the number would be, if not 4 percent, if Texas had been federally regulated. He answered “0 percent”. Let’s have a look at Mississippi, which has federal regulation and has suffered from a similar cold snap. 13.5 percent of customers in MS are out as of the same time as the above map:

How about Louisiana?

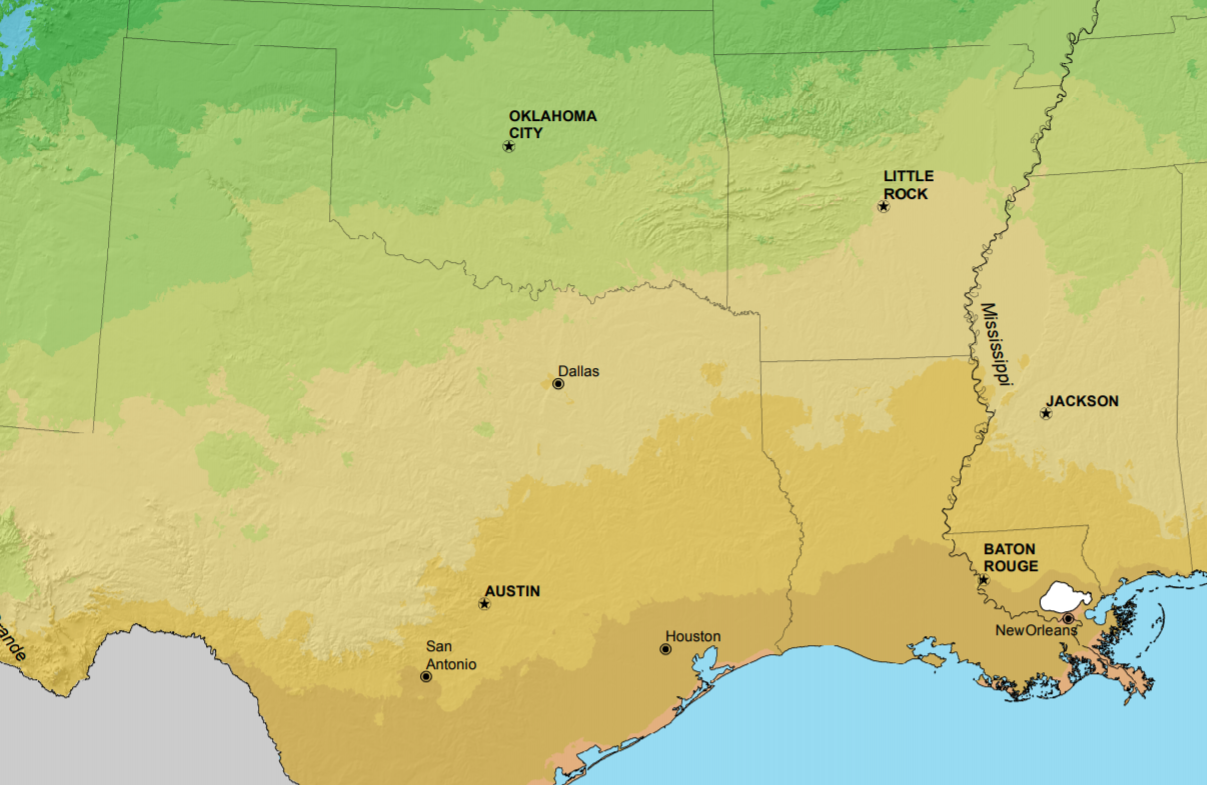

Across the three states, it looks as though the outages line up with the USDA Zone 8b (Austin, Texas being included in this zone).

In other words, a cold snap in Zone 8b results in power failures whether the grid is regulated by the feds or the state. (The failures were slightly different in character, with Texas knocked out by high demand while MS and LA suffered from both excess demand and power lines downed by the ice and snow. Both could have been avoided, however, with additional $$ invested in preparation.)

Update, Feb 20, 11:00 am: 6 percent of folks in Mississippi are still without power, mostly in Zone 8b and some in Zone 8a.

(Texas, where the outages started earlier, is 99.4% powered (0.6% without power).)

Related:

- Austin and Lockhart, Texas: 10 barbecue restaurants in 72 hours (fortunately, the smokers will continue to operate without power)

- “The Texas Freeze: Why the Power Grid Failed” (WSJ) sounds like a great analysis. Companies that generate power aren’t paid to sit on standby, so there is an undersupply of standby power, especially during cold snaps when it would be expensive to prep a plant to keep operating. A big nuclear plant tripped off due to a water supply freeze. The authors attribute the problems to the way Texas set up its market for electric power, e.g., paying only for power delivered and not for being ready. But they never look at why the grid failures were nearly as bad in Louisiana and Mississippi. Maybe this is like coronascience and it is only necessary to tell a good story after data are received?

- February 2013 North American blizzard (Wikipedia), in which 18 people died, the power failed, and it was both illegal and impractical to travel by road here in Maskachusetts.

- Northeastern United States blizzard of 1978 (Wikipedia) in which 100 people died.

Very loosely related…

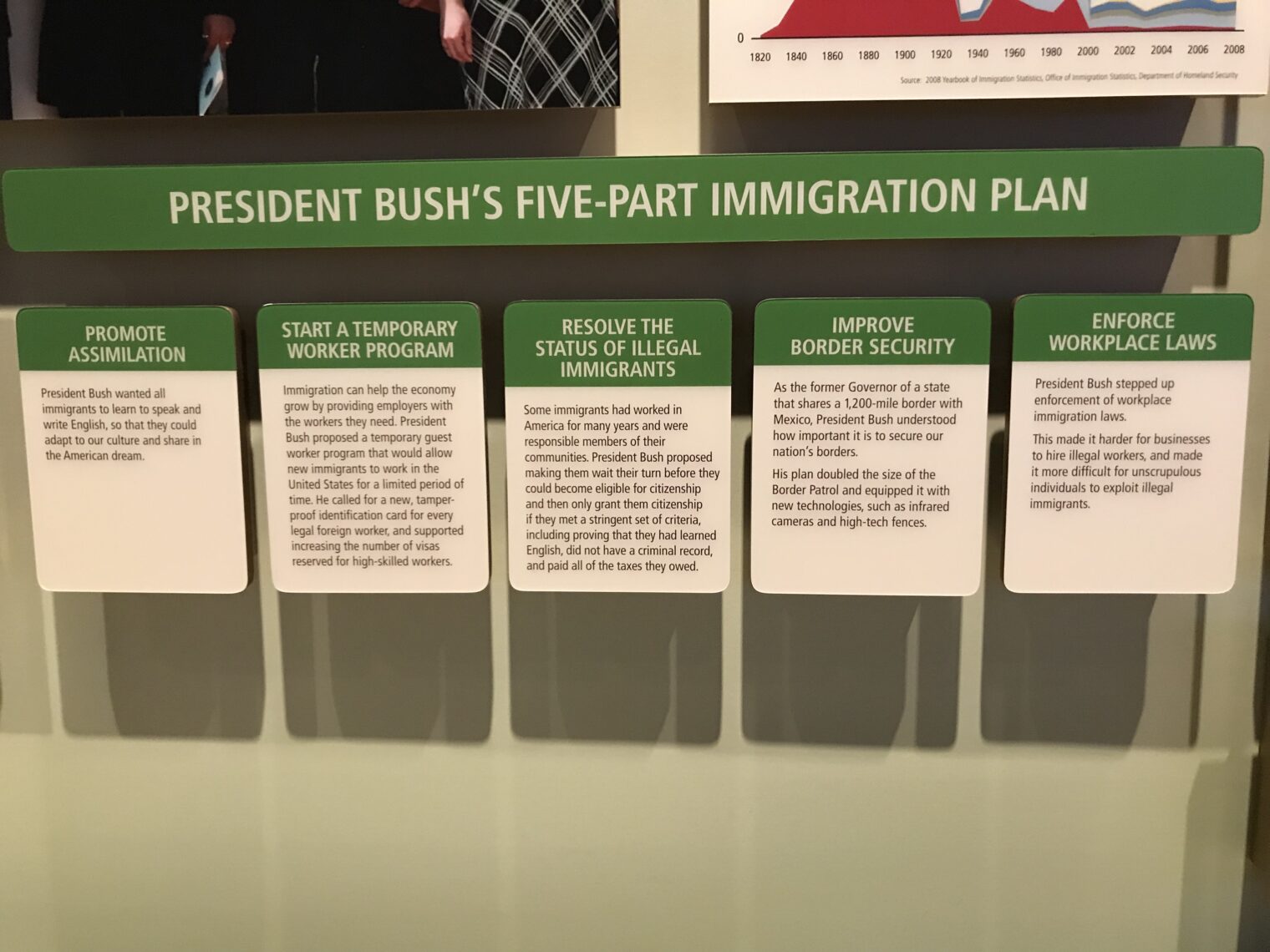

From a 2018 business trip to Dallas, extended due to 50-knot winds in the Northeast and the cancellation of airline flights back home, the George W. Bush Presidential Library (closed for a year now due to coronapanic):

And from the art museum, an unfortunately timely painting, Frederic Edwin Church’s The Icebergs:

Full post, including comments