If an 86-year-old can be President, can a union boss become a mom at age 60?

“Greene faces pushback after saying Weingarten is ‘not a mother’” (The Hill):

Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-Ga.) is facing pushback after suggesting that American Federation of Teachers (AFT) President Randi Weingarten, who’s a stepmother, is “not a mother.”

“The problem is people like you need to admit that you’re just a political activist, not a teacher, not a mother and not a medical doctor,” Greene said.

Rep. Robert Garcia (D-Calif.) stepped in with a point of order after Greene’s comments, calling them “unacceptable.” … “You are a mother,” he added to Weingarten. “Thank you for being a great parent.”

The journalists report as a fact that Mx. Weingarten, age 65, is a “stepmother”. Wikipedia says that Mx. Weingarten’s marriage was in 2018, when he/she/ze/they was 60 years old. Mx. Weingarten married Sharon Kleinbaum, at least 58 years old at the time. If we assembled Kentaji Brown Jackson’s panel of biologists, I think they would likely say that Mx. Kleinbaum’s children were fully grown by the time the “rabbi” was 58 (rabbi in quotes because the congregation led by Mx. Kleinbaum is “not affiliated with any denomination or branch of Judaism.”). Thus, we would need a definition of parent as something that did not require “caring for a human under age 18”.

If I were to marry Warren Buffett, for example, would Democrats say that I was a “stepdad” to his 64-year-old youngest son?

Another quote from Greene at the hearing from Yahoo! News:

“I didn’t ask you a question. What I would like to talk about is your recommendations to the CDC, as not a medical doctor, not a biological mother, and really not a teacher, either. So, what you did is you advised the CDC?” Greene said.

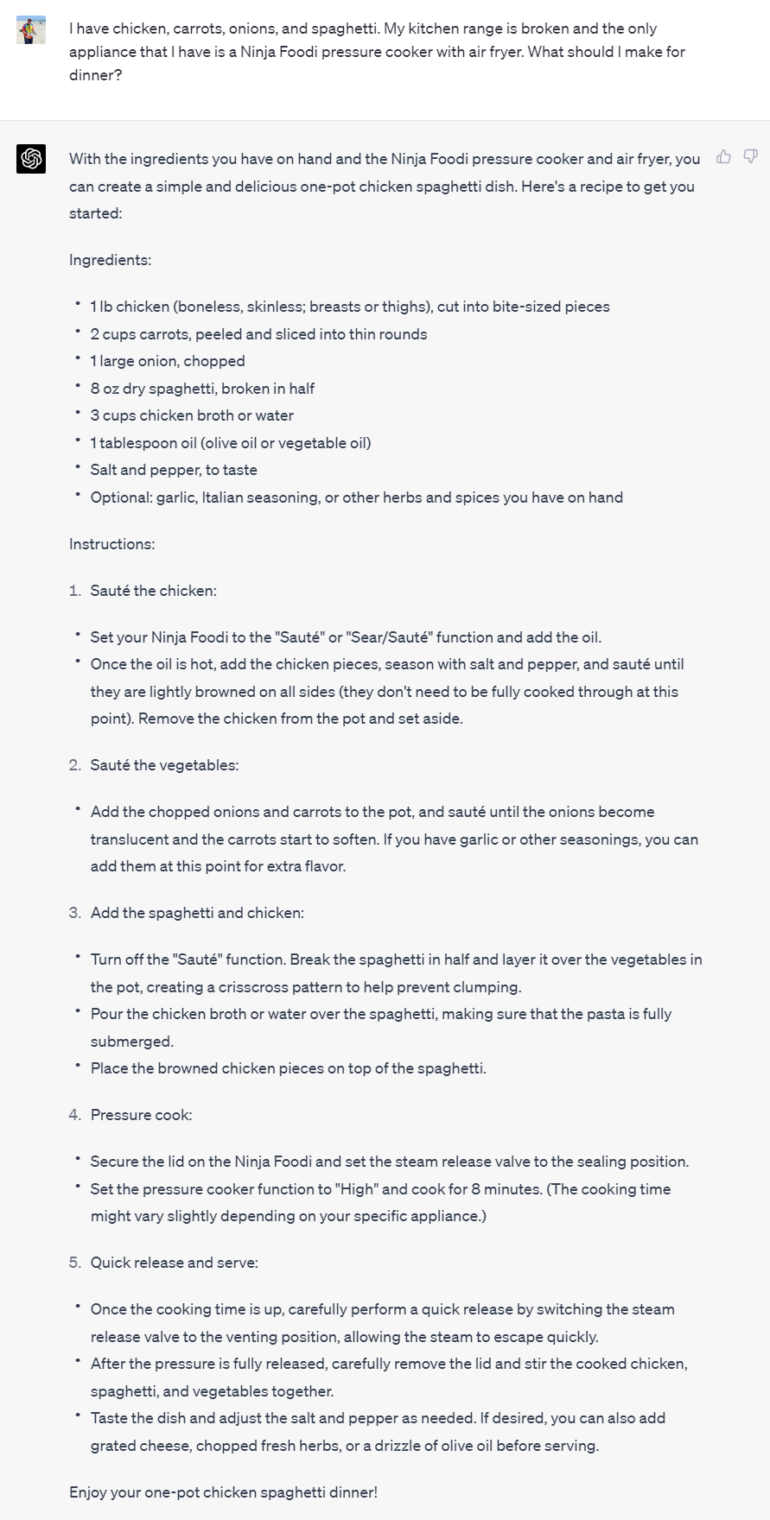

My personal efforts in this area haven’t been very successful. When the kids were younger I explained to them that the reason Mindy the Crippler, our golden retriever, was so tightly bonded to me was that I had given birth to her and then nursed her for 8 weeks. They refused to accept my status as a dog mom and cited Mindy’s biological mom, Chaos, as the animal’s only real mother. More recently, I used the “Mother’s Room” at a downtown Boston law firm to change from MIT teaching outfit (jeans and Oshkosh T-shirt) into testifying-at-trial outfit. For this, I was mocked by a couple of female executives from Brazil. I said “This is Massachusetts and it is my right to identify as a mother any time that I want. In fact, I can be more of a mother than either of you will ever be.” Apparently Fox News and MTG are also popular in Brazil because they responded, “You can call yourself whatever you want, but don’t expect us to cooperate.”

Related:

- “As More Teachers’ Unions Push for Remote Schooling, Parents Worry. So Do Democrats.” (New York Times, January 2022) (Democrats need not have worried! We can infer from the fall 2022 elections that voters nationwide love nothing more than closed schools.)

- “Teachers Are Wary of Returning to Class, and Online Instruction Too” (NYT, July 2022): Unions are threatening to strike if classrooms reopen, but are also pushing to limit live remote teaching. Their demands will shape pandemic education. (summary: Mx. Weingarten’s unionized teachers wanted to collect paychecks while neither working in the classroom nor at home)