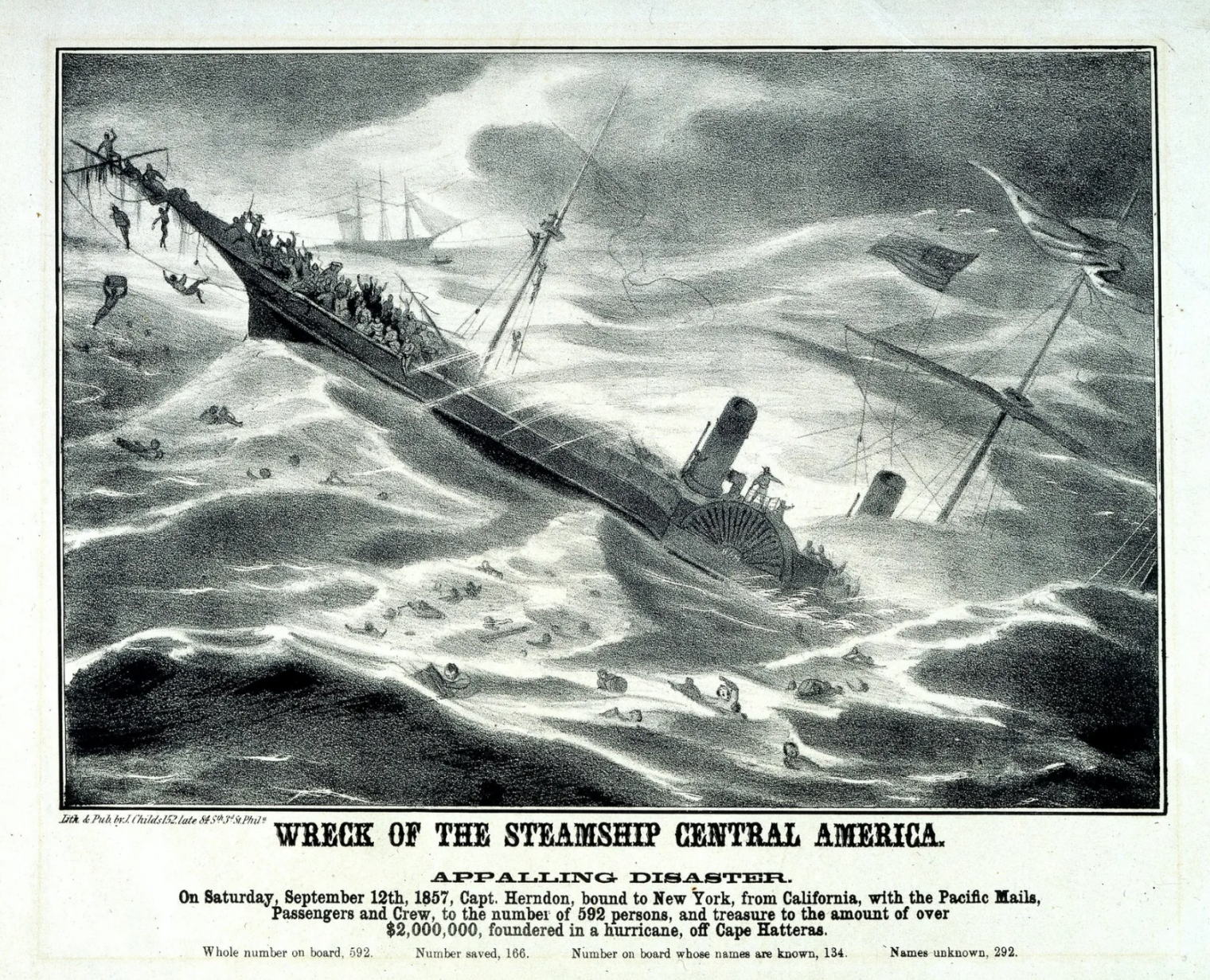

On this Memorial Day I’d like to celebrate the memory of William Lewis Herndon, author of Exploration of the Valley of the Amazon and captain of the SS Central America, a commercial ship with a U.S. Navy captain that sank off the Carolinas during a hurricane in 1857, resulting in a loss of 425 lives, mostly people returning from the California Gold Rush. Herndon could have escaped with his life, but chose to go down with the ship after ensuring that all women and children had been evacuated (including Lucy Dawson, the only black woman on board; we are informed today that Americans in 1857 were irredeemably racist, yet white men gave up their lives so that Ms. Dawson could keep hers).

Herndon is described in Ship of Gold in the Deep Blue Sea: The History and Discovery of the World’s Richest Shipwreck (Gary Kinder, 1998):

Married and the father of one daughter, Herndon was slight, and at forty-three balding; a red beard ran the fringe of his jaw from temple to temple. Though he looked like a professor or a banker more than a sea captain, he had been twenty-nine years at sea, in the Mexican War and the Second Seminole War, in the Atlantic and the Pacific, the Mediterranean and the Caribbean Sea. He knew sailing ships and steamers and had handled both in all weather. He was also an explorer, internationally known and greatly admired, who had seen things no other American and few white men had ever seen.

Herndon ordered Ashby and his first officer not to let a single man into the boats until all of the women and children were off. “While they were getting into the boats,” observed one man from the bailing lines, “there was the utmost coolness and self-control among the passengers; not a man attempted to get into the boats. Captain Herndon gave orders that none but the ladies and children should get into the boats, and he was obeyed to the letter.”

The ship took 30,000 lbs. of gold 8,000′ underwater, which is what led to the main story of the above book. This cargo was worth $8 million at the time and roughly 1 billion Bidies today (inflation of 125X or 12,500 percent).

If you can tolerate an old-style book in which race, gender ID, and sexual orientation are seldom mentioned, the story of engineering challenges being addressed one after another is fascinating. The hero of the book is Tommy Thompson, a self-motivated engineer who attends Ohio State, works for Key West treasure hunter Mel Fisher, and comes back to work for Batelle. While at Batelle, he comes up with the idea of salvaging wrecks in the deep ocean.

“A galleon drafted about fifteen feet,” Tommy told Bob, “so they generally hit reefs in about fifteen feet of water. It is not like men to leave gold lying in fifteen feet of water.” Most of the artifacts Fisher had found were at twelve feet, and the only reason Spanish salvage divers had not completely stripped the Atocha in 1622 is because a second, far bigger storm had hit the wreck site three weeks later.

During the three centuries following Columbus’s voyages to the New World, much of the gold and silver on earth had been transferred from the New World to the Old World, and 25 percent of it had been lost. But don’t search for it among the thousands of shallow-water shipwrecks in the Caribbean, said Tommy; the odds were too slim. Search for treasure where storms couldn’t buffet the remains, where ships were not piled on top of each other, where the bottom was hard and the currents slow, and where no government could stake a claim. Tommy told Bob he wanted to recover historic shipwrecks in the deep ocean.

A key enabler of the quest for the Central America‘s gold is Martin Klein, the inventor of practical side scan sonar, but this MIT graduate is not credited by the author. Once found, however, there is a question of how to conduct mining operations on the ocean floor with mid-1980s technology.

If you got your submersible safely into the water, your ship at the surface was rising and falling while your submersible was descending; each fall caused the cable to go slack, and each rise snapped the cable taut, like pulling a car with a chain. That load suddenly became ten times heavier than the submersible itself, and the cable often broke and you lost your submersible. That armored cable was filled with electromechanical wires that carried signals down to the sub and back again. If the snap loading didn’t break it, every time that cable passed over a pulley, the wires bent and straightened with the weight of the vehicle, and often ten times the weight of the vehicle, and the wires fatigued and parted. A replacement cable took three months to manufacture, and carrying a spare cable on board meant needing more space on a bigger ship, tended by a larger crew, for much more money. Attempting to land on the seafloor was risky and difficult for two reasons: First, the rocking of the ship would jerk the vehicle—one minute you’d be looking at the bottom, the next minute you’d see nothing, the next minute the camera would be in the mud. Second, hanging something heavy on the end of a cable twisted the cable; if you set that heavy weight on the seafloor and slackened the cable at the same time, the twisted cable tied itself in knots, like the cord on a telephone. When an armored cable with several thousand pounds on the end kinked up, and the bouncing of the ship topside jerked on those kinks, the cable again often broke, which meant you left your vehicle on the bottom and headed back to the beach for the rest of the season.

Everyone who had previously worked in this area was funded by militaries, which had essentially unlimited budgets to look for sunken submarines and similar valuable items. Tommy Thompson needed to do the job for $millions when others had failed with $1 billion budgets. There’s also an interesting legal challenge:

The Central America lay at the far reaches of the Economic Zone, almost two hundred miles offshore. No one had ever tried to recover an historic shipwreck so deep it lay beyond the three-mile boundary. Tommy could bring a piece of the Central America into the courtroom, but no one knew what would happen next.

One of the more unusual challenges was how to bring up gold coins without scratching them, which would reduce their value to collectors. The team of salvors came up with the idea of a silicone injection process that would embed gold objects in a block of the soft substance before it was all brought to the surface.

If you love engineering, I recommend Ship of Gold in the Deep Blue Sea. Even if you don’t love engineering, I hope that you’ll join me in remember Captain Herndon and his decades of service in what was a hazardous job back then (wooden ships combined with no GPS and no weather forecasts).

(Since 1998, Mr. Thompson’s career has developed some warts. I don’t want to spoil the book for you, but let’s just say that, as in family court, a big pot of gold can lead to accusations of unfairness.)

Related:

Full post, including comments