UC Davis applies UC Davis research to create unsuccessful physicians

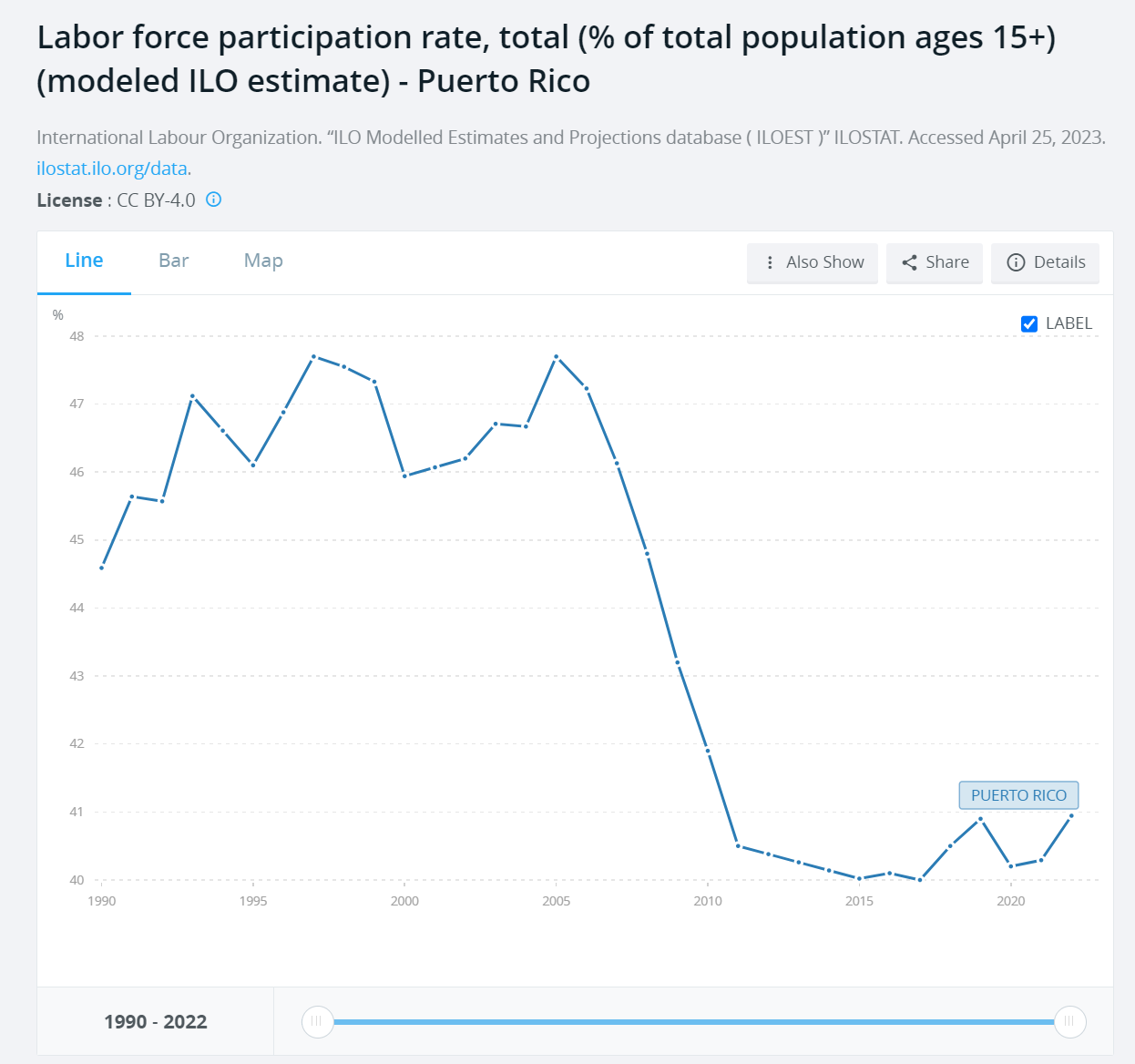

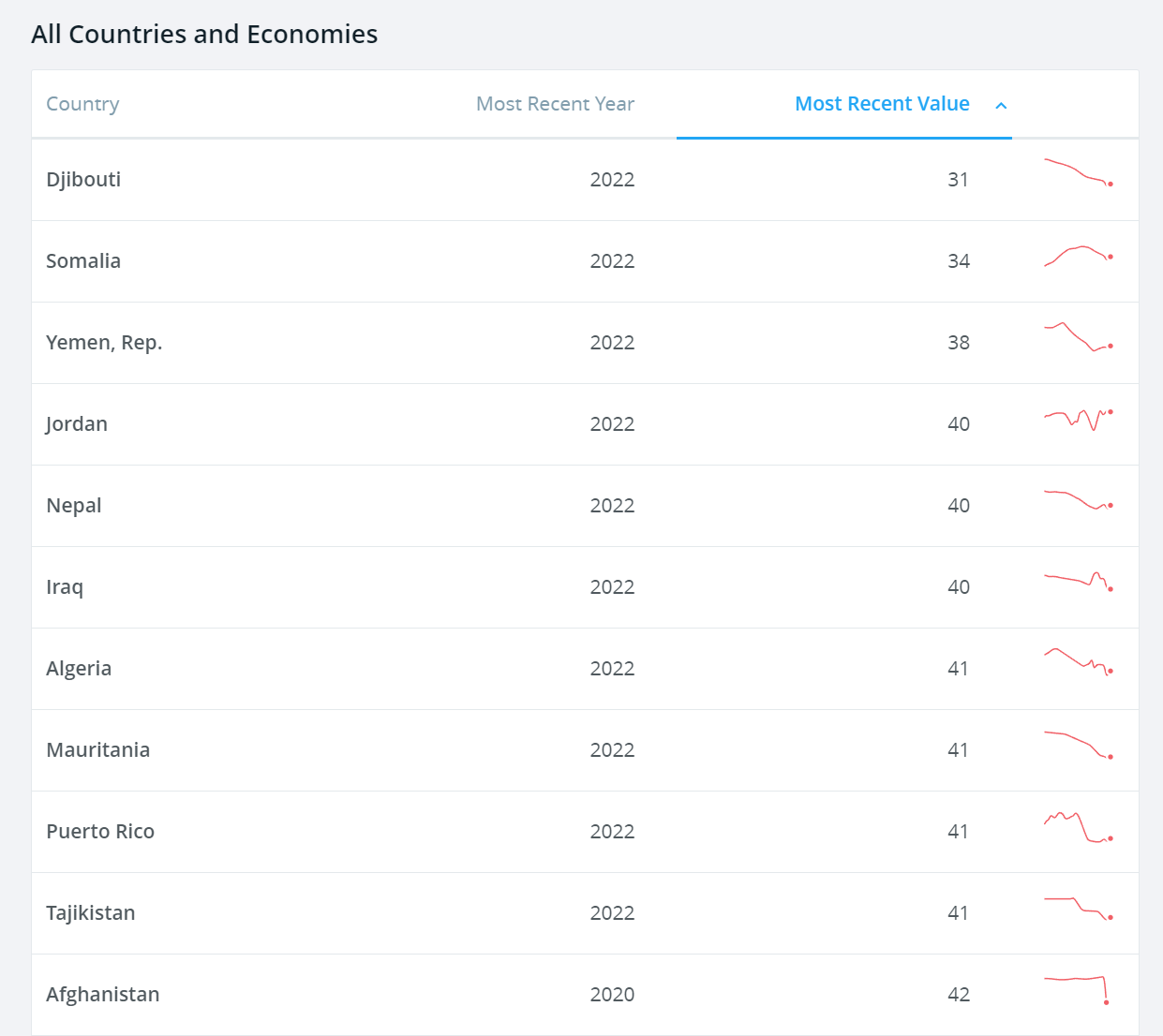

Econ nerds at University of California, Davis did a huge study across hundreds of years of history and came to the conclusion that success was heritable, just as intelligence and conscientiousness tend to be genetically determined (see “The heritability of conscientiousness facets and their relationship to IQ and academic achievement”). I summarized this research in the following blog posts:

- The Son Also Rises: economics history with everyday applications

- The Son Also Rises: Tips for Optimizing Your Life

- The Son Also Rises: Policy Implications

How is UC Davis applying its own research? “With End of Affirmative Action, a Push for a New Tool: Adversity Scores” (New York Times, July 2):

The scale rates every applicant from zero to 99, taking into account their life circumstances, such as family income and parental education. Admissions decisions are based on that score, combined with the usual portfolio of grades, test scores, recommendations, essays and interviews.

In other words, if your parents were unsuccessful, UC Davis wants you as a medical student!

The NYT article actually confirms the UC Davis economists’ conclusions:

There is also a family dynamic. Children of doctors are 24 times more likely to become doctors than their peers, according to the American Medical Association. It’s hard to know why the profession passes down from generation to generation, but the statistic drove the association to adopt a policy opposing legacy preferences in admissions.

The tendencies to enjoy sitting in biology lectures, studying for tests, and slicing up cadavers are “passed down from generation to generation” but the Followers of Science at the New York Times can’t come up with an explanatory mechanism.

Separately, let’s have a look at UC Davis’s most famous recent pre-med major, Carlos Dominguez. KCRA:

Dominguez came to the U.S. near Galveston, Texas in 2009 from El Salvador.

A U.S. and Immigration and Customs Enforcement official confirmed to KCRA 3 that ICE has placed a detainer with the Yolo County Sheriff’s Office, which means the agency would take custody of Dominguez should he be released from local custody.

Detainers are requests to state or local law enforcement agencies to remove non-citizens arrested for criminal activity once they have been released from their custody.

The ICE official referred to Dominguez as Carlos Alejandro Reales-Dominguez and said his immigration case had been closed in April 2012. He had come to the U.S. as an unaccompanied minor from El Salvador in 2009 near Galveston, Texas, and was transferred to a family member at the time.

Mr. Dominguez thus will qualify for preferential admission to UC Davis Medical School due to the adversities of (1) being an undocumented immigrant, and (2) having an encounter with our racist criminal justice system.

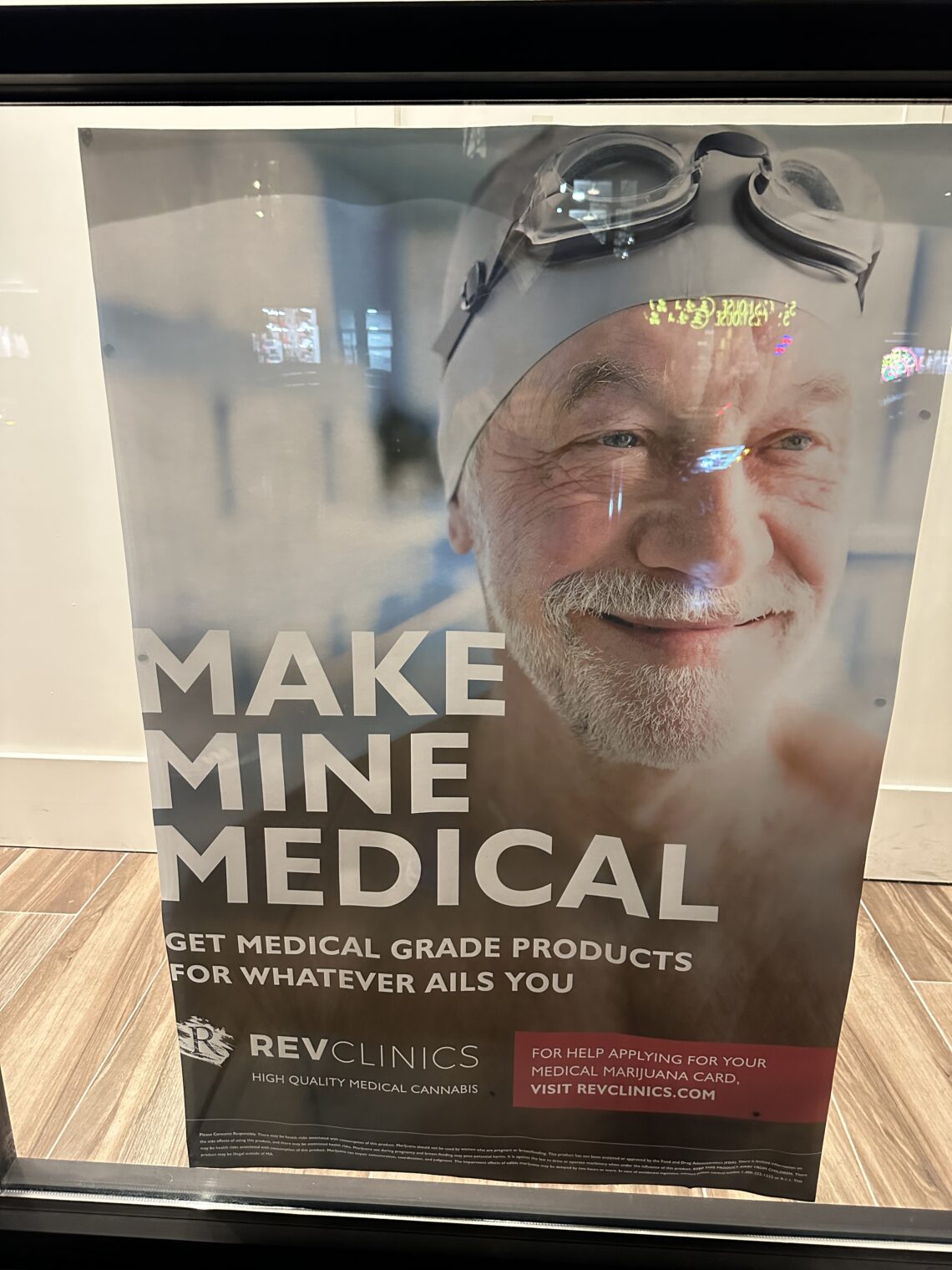

The good news for folks who actually live in Davis, California, is that their health is guaranteed to be excellent because the town is rich in (“essential”) marijuana:

Full post, including comments