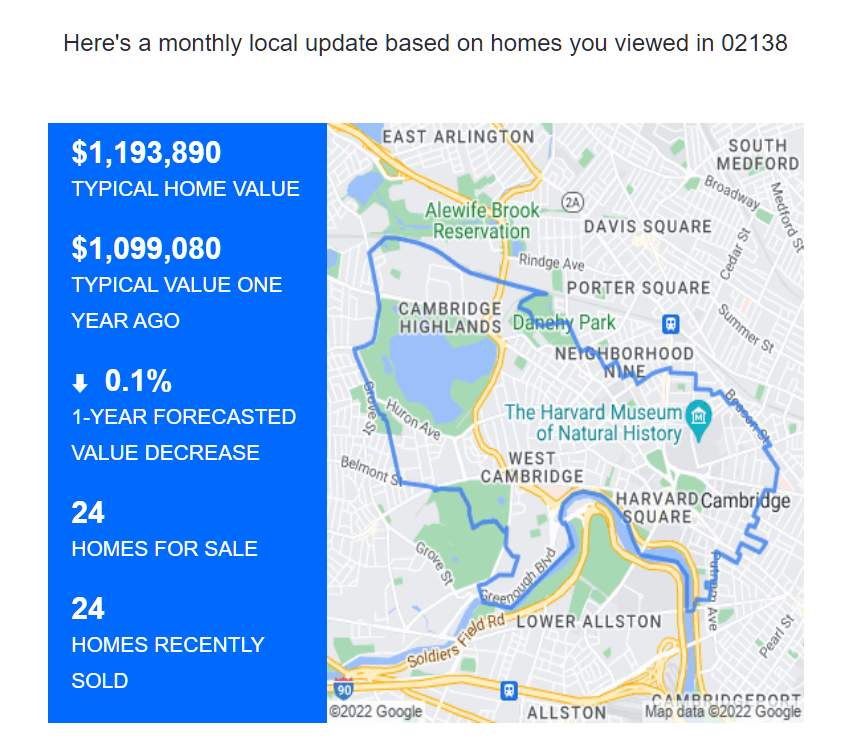

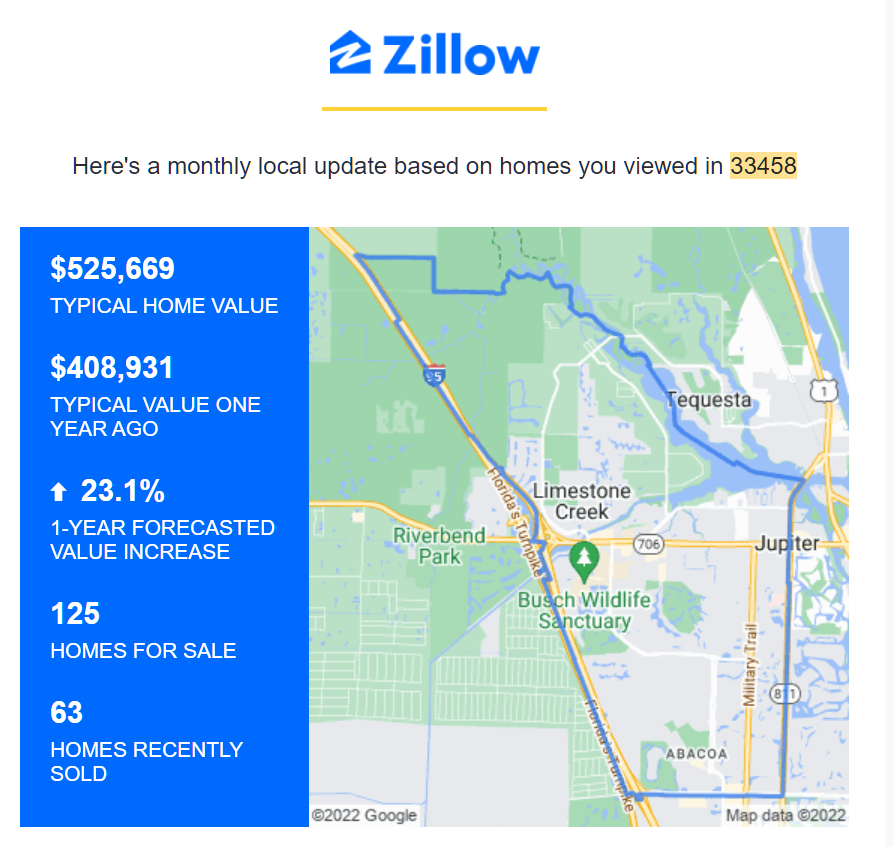

From February 2022, when we were dumb enough to sign a contract to buy a house:

The market will go up 23%.

In April, when we were dumb enough to close on a house:

The market has gone up a little and will go up 18.3 percent more.

In June, Zillow is busy celebrating Pride Month (from 2020: “They’re bold, bright and one-of-a-kind — they’re the homes we love, Pride-month style. We may not be celebrating together in person, but we’ll never stop celebrating what’s beautiful.”), but the company’s robot still has time to say that the forecast is 14.6 percent:

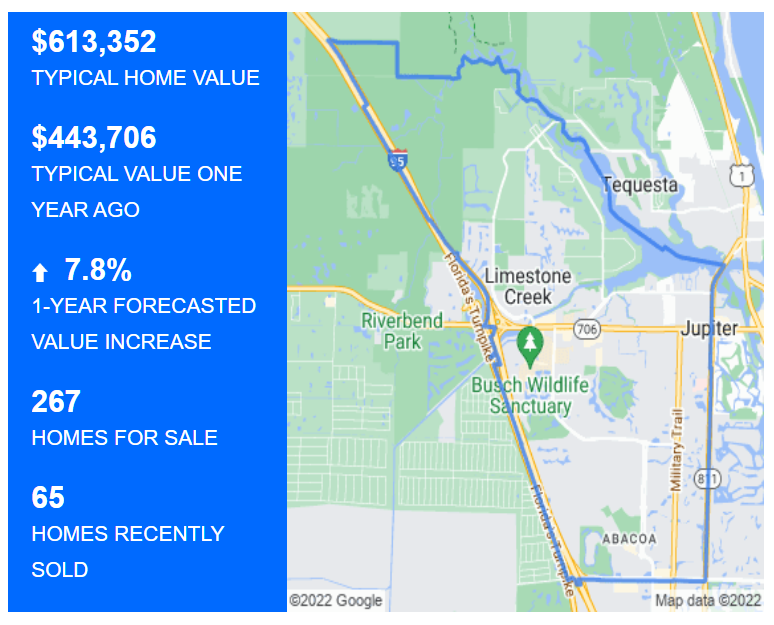

August 5, 2022, the “typical home value” is up by a staggering amount and the forecast is 7.8 percent more:

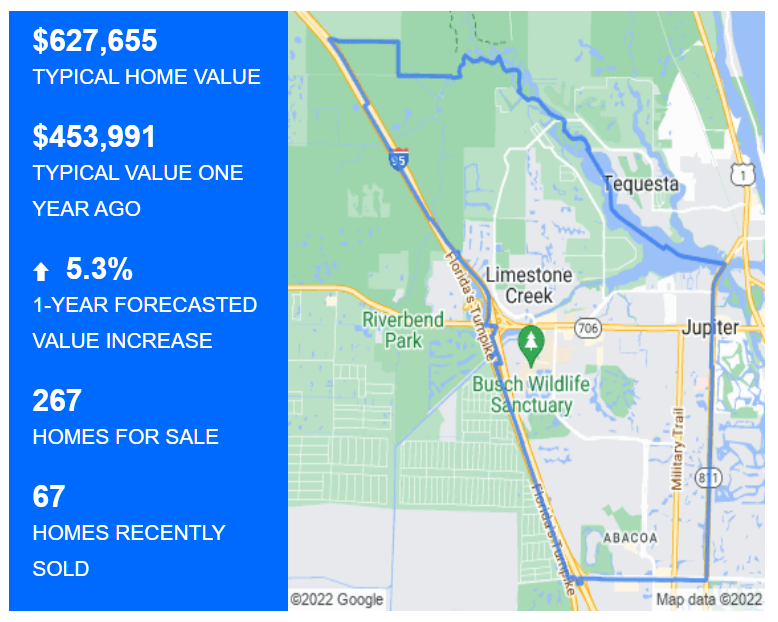

August 14, 2022, the “typical home value” is still up (yet houses have seemingly been slow to sell for a few months now and there have been many price cuts) and, with the Inflation Reduction Act nearly signed by the vigorous Vanquisher of Corn Pop, the inflation forecast is down to 5.3 percent:

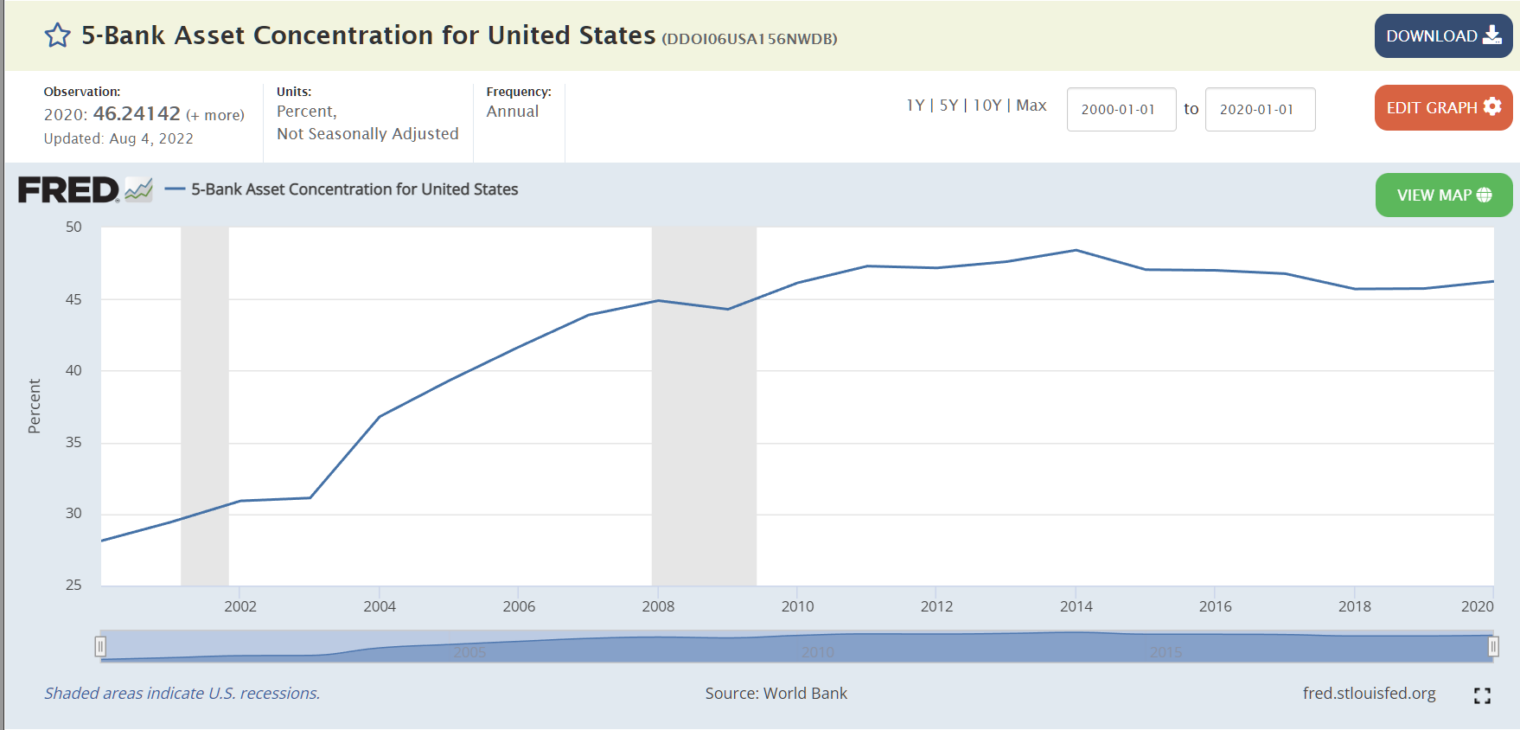

These forecasts aren’t mutually inconsistent. If we take the starting “typical home value” and inflate it by the forecast 23.1 percent increase we get $647,098 for the expected typical home value in February 2023. If, indeed, the current value is already $627,655, the forecast 5.3 percent inflation rate (to August 2023) will make that happen.

Do we believes these precise forecasts? If so, should Joe Biden ask Zillow to come in and take over the Fed?

Separately, speaking of house price inflation, it occurs to me that the capital gains tax applied to homeowners does not make any sense. Suppose that Dana Dentist, a gender-neutral driller of teeth, purchased a 4BR house for $500,000 fifteen years ago. Dana falls in love with someone he/she/ze/they met at a Pride March in another city. Dana sells his/her/zir/their house for $1.5 million (in 2022 mini-dollars) and buys an identical size/quality house in the new sweetheart’s city, which just so happens to cost $1.5 million. Dana is no better off. He/she/ze/they has exactly the same size and quality of house. Yet the IRS now hits him/her/zir/them for capital gains and Obamacare investment income tax on $750,000 (the first $250,000 of gain on a primary residence is exempt). There may be state capital gains taxes to pay as well if Dana did not live in Texas, Florida, or a similar state.

Note that this wouldn’t happen to a commercial property owner. If he/she/ze/they sold House 1, which had been rented out, and bought House 2 in order to rent it out, the sale/purchase would be done in a 1031 exchange and there would be no tax on the fictitious capital gain until, perhaps, House 2 was sold and not replaced.

What’s the downside of the Feds and states taxing fictitious capital gains? By making moving more expensive, the policy discourages people from moving for better career opportunities and, thus, reduces the overall growth rate of the U.S. economy (not as much as our family law system does, but at least to some extent).

Full post, including comments